“Perfect. I have to see Simpson, but I can meet you after that. Is one all right with you?”

“Fine. And Kezia …”

“Yes?” Her voice was low and gentle, suddenly not quite so brisk. In her own way, she loved him too. For almost twenty years now, he had softened the blow of the absence of her father.

“It really is good to know you’re back.”

“And it really is good to know that someone gives a damn.”

“Silly child, you make it sound as though no one else cares.”

“It’s called the Poor Little Rich Girl Syndrome, Edward. Occupational hazard for an heiress.” She laughed, but there was an edge to her voice that troubled him. “See you at one.”

She hung up, and Edward stared out at the view.

Twenty-two blocks from where he sat, Kezia was lying in bed, finishing her tea. There was a stack of newspapers on her bed, a pile of mail on the table next to her. The curtains were drawn back, and she had a peaceful view of the garden behind the townhouse next door. A bird was cooing on the air conditioner. And the doorbell was ringing.

“Damn.” She pulled a white satin robe off the foot of the bed, wondering who it might be, then suspecting quickly. She was right. When she opened the door, a slim, nervous Puerto Rican boy held out a long white box.

She knew what was in the box even before she traded the boy a dollar for his burden. She knew who the box was from. She even knew the florist. And knew also that she would recognize his secretary’s writing on the card. After four years, you let your secretary write the cards: “Oh, you know, Effy, something like ‘You can’t imagine how I’ve missed you,’ et cetera.” Effy did a fine job of it. She said just what any romantic fifty-four-year-old virgin would say on a card to accompany a dozen red roses. And Kezia didn’t really care if the card was from Effy or Whit. It didn’t make much difference anymore. None at all, in fact.

This time Effy had added “Dinner tonight?” to the usual flowery message, and Kezia paused with the card in her hand. She sat down in a prim blue velvet chair that had been her mother’s, and played with the card. She hadn’t seen Whit in a month. Not since he had flown to London on business, and they had partied at Annabelle’s before he left again the next day. Of course he had met her at the airport the night before, but they hadn’t really talked. They never really did.

She leaned pensively toward the phone on the small fruitwood desk, the card still in her hand. She glanced across the neat stacks of invitations her twice-weekly secretary had arranged for her-those she had missed, and those that were for the near and reasonably near future. Dinners, cocktails, gallery openings, fashion shows, benefits. Two wedding announcements, and a birth announcement.

She dialed Whit’s office and waited.

“Up already, Kezia darling? You must be exhausted.”

“A bit, but I’ll live. And the roses are splendid.” She allowed a small smile to escape her and hoped that it wouldn’t show in her voice.

“Are they nice? I’m glad. Kezia, you looked marvelous last night.” She laughed at him and looked at the tree growing in the neighboring garden. The tree had grown more in four years than Whit had.

“You were sweet to pick me up at the airport. And the roses started my day off just right. I was beginning to gloom over unpacking my bags.”

She had had the bad judgment to arrive on one of the cleaning woman’s days off. But the bags could wait.

“And what about my dinner invitation? The Orniers are having a dinner, and if you’re not too tired, Xavier suggested we all go to Raffles afterwards.” The Orniers had an endless suite in the tower at the Hotel Pierre, which they kept for their annual trips to New York. Even for a few weeks it was “worth it”: “You know how ghastly it is to be in a different room each time, a strange place.” They paid a high price for familiarity, but that was not new to Kezia. And their dinner party was just the sort of thing she ought to cover for the column. She had to get back into the swing of things, and lunch at La Grenouille with Edward would be a good start, but … damn. She wanted to go downtown instead. There were delights downtown that Whit would never dream she knew. She smiled to herself and suddenly remembered Whit in the silence.

“Sorry, darling. I’d love to, but I’m so awfully tired. Jet lag, and probably all that wild life at Hilary’s this weekend. Can you possibly tell the Orniers I died, and I’ll try to catch a glimpse of them before they leave. For you, I will resurrect tomorrow. But today, I’m simply gone.” She yawned slightly, and then giggled. “Good Lord, I didn’t mean to yawn in your ear. Sorry.”

“Quite all right. And I think you’re right about tonight. They probably won’t serve dinner till nine. You know how they are, and it’ll be two before you get home after Raffles. …” Dancing in that over-decorated basement, Kezia thought, just what I don’t need. …

“I’m glad you understand, love. Actually, I think I’ll put my phone on the service, and just trot off to bed at seven or eight. And tomorrow I’ll be blazing.”

“Good. Dinner tomorrow then?” Obviously, darling. Obviously.

“Yes. I have a thing on my desk for some sort of gala at the St. Regis. Want to try that? I think the Marshes are taking over the Maisonette for their ninety-eighth wedding anniversary or something.”

“Nasty sarcastic girl. It’s only their twenty-fifth. I’ll take a table at La Côte Basque, and we can go next door late.”

“Perfect, darling. Till tomorrow, then.”

“Pick you up at seven?”

“Make it eight.” Make it never.

“Fine, darling. See you then.”

She sat swinging one leg over the other after she hung up. She really was going to have to be nicer to Whit. What was the point in being disagreeable to him? Everyone thought of them as a couple, and he was nice to her, and useful in a way. Her constant escort. Darling Whitney … poor Whit. So predictable and so perfect, so beautiful and so impeccably tailored. It was unbearable really. Precisely six feet and one inch, ice-blue eyes, short thick blond hair, thirty-five years old, Gucci shoes, Dior ties, Givenchy cologne, Piaget watch, apartment on Park and Sixty-third, fine reputation as a lawyer, and loved by all his friends. The obvious mate for Kezia, and that in itself was enough to make her hate him, not that she really hated him. She only resented him, and her need of him. Despite the lover on Sutton Place that he didn’t know she knew about.

The Whit and Kezia game was a farce, but a discreet one. And a useful one. He was the ideal and eternal escort, and so totally safe. It was appalling to remember that a year or two before she had even considered marrying him. There didn’t seem any reason not to. They would go on doing the same things they were doing, and Kezia would tell him about the column. They would go to the same parties, see the same people, and lead their own lives. He’d bring her roses instead of send them. They would have separate bedrooms, and when Kezia gave someone a tour of the house Whit’s would be shown as “the guest room.” And she would go downtown, and he to Sutton Place, and no one would have to be the wiser. They would never mention it to each other, of course; she would “play bridge” and he would “see a client,” and they would meet at breakfast the next day, pacified, mollified, appeased, and loved, each by their respective lovers. What an insane fantasy. She laughed thinking back on it now. She still had more hope than that. She regarded Whit now as an old friend. She was fond of him in an odd way. And she was used to him, which in some ways was worse.

Kezia wandered slowly back to her bedroom and smiled to herself. It was good to be home. Nice to be back in the comfort of her own apartment, in the huge white bed with the silver fox bedspread that had been such an appalling extravagance, but still pleased her so much. The small, delicate furniture had been her mother’s. The painting she had bought in Lisbon the year before hung over the bed, a watermelon sun over a rich countryside and a man working the fields. There was something warm and friendly about her bedroom that she found nowhere else in the world. Not in Hilary’s palazzo in Marbella, or in the lovely home in Kensington where she had her own room-Hilary had so many rooms in the London house that she could afford to give them away to absent friends and family like so many lace handkerchiefs. But nowhere did Kezia feel like this, except at home. There was a fireplace in the bedroom too, and she had found the brass bed in London years before; there was one soft brown velvet chair near the fireplace, and a white fur rug that made you want to dance barefoot across the floor. Plants stood in corners and hung near the windows, and candles on the mantel gave the room a soft glow late at night. It was very good to be home.

She laughed softly to herself, a sound of pure pleasure as she put Mahler on the stereo and started her bath. And tonight … downtown. To Mark. First, her agent, then lunch with Edward. And finally, Mark. Saving the best till last … as long as nothing had changed.

“Kezia,” she spoke aloud to herself, looking in the bathroom mirror as she stood naked before it, humming to the music that echoed through the house, “You are a very naughty girl!” She wagged a finger at her reflection, and tossed back her head and laughed, her long black hair sweeping back to her waist. She stood very still then and looked deep into her own eyes. “Yeah, I know. I’m a rat. But what else can I do? A girl’s got to live, and there are a lot of different ways to do it.” She sank into the bathtub, wondering about it all. The dichotomies, the contrasts, the secrets … but at least no lies. She said nothing to anyone. But she did not lie. Almost never anyway. Lies were too hard to live with. Secrets were better.

As she sank into the warmth of the water, she thought about Mark. Delicious Marcus. The wild crazy hair, the incredible smile, the smell of his loft, the chess games, the laughter, the music, his body, his fire. Mark Wooly. She closed her eyes and drew an imaginary line down his back with the tip of one finger and then traced it gently across his lips. Something small squirmed low in the pit of her stomach, and she turned slowly in the tub, sending ripples gently away from her.

Twenty minutes later she stepped out of the bath, brushed her hair into a sleek knot, and slipped a plain white wool Dior dress over the new champagne lace underwear she had bought in Florence.

“Do you suppose I’m a schizophrenic?” she asked the mirror as she carefully fitted a hat into place and tilted it slowly over one eye. But she didn’t look like a schizophrenic. She looked like “the” Kezia Saint Martin, on her way to lunch at La Grenouille in New York, or Fouquet’s in Paris.

“Taxi!” Kezia held up an arm and dashed past the doorman as a cab stopped a few feet away at the curb. She smiled at the doorman and slid into the cab. Her New York season had just begun. And what did this one have in store? A book? A man? Mark Wooly? A dozen juicy articles for major magazines? A host of tiny cherished moments? Solitude and secrecy and splendor. She had it all. And another “season” in the palm of her hand.

In his office, Edward was strutting in front of the view. He looked at his watch for the eleventh time in an hour. In just a few minutes he would watch her walk in, she would see him and laugh, and then reach up and touch his face with her hand … “Oh Edward, it’s so good to see you!” She would hug him and giggle, and settle in at his side-while “Martin Hallam” took mental notes about who was at what table with whom, and K. S. Miller mulled over the possibility of a book.

Chapter 2

Kezia fought her way past the tight knot of men hovering between the cloak room and the bar of La Grenouille. The luncheon crowd was thick, the bar was jammed, the tables were full, the waiters were bustling, and the decor was unchanged. Red leather seats, pink tablecloths, bright oil paintings on the walls, and flowers on every table. The room was full of red anemones and smiling faces, with silver buckets of white wine chilling at almost every table while champagne corks popped demurely here and there.

The women were beautiful, or had worked hard at appearing so. Cartier’s wares were displayed in wild profusion. And the murmur of conversation throughout the room was distinctly French. The men wore dark suits and white shirts, and had gray at their temples, and shared their wealth of Romanoff cigars from Cuba via Switzerland in unmarked brown packages.

La Grenouille was the watering hole of the very rich and the very chic. Merely having an ample expense account to pay the tab was not adequate entree. You had to belong. It had to be part of you, a style you exuded from the pores of your Pucci.

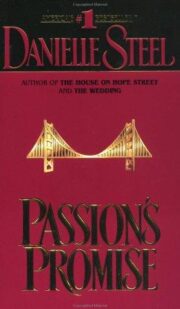

"Passion’s Promise" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passion’s Promise". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passion’s Promise" друзьям в соцсетях.