After dinner Tom slipped away from the house and came down to the quarters, to sit for a time beside Bev’s bed, holding his son’s hand and anxiously studying his face. When the children were well, Sally reflected, as she tied up bundles of herbs to dry, Tom treated them with the same friendly affection with which he treated all the children in the quarters. Plantation gossip being what it was, he could do nothing else. But Harriet’s death had shaken him, more than he would ever express. In his face tonight she saw his anxiety, and when he spoke to her—the soft-voiced commonplaces of treatment, of herbs and symptoms—she thought she heard sadness and guilt there as well.

They had been united as partners for a dozen years—as long as his marriage to Miss Patty. If the desperation of her first love for him had not survived the years, it had settled into an acceptance of him, and a deep-rooted affection.

He would never be other than he was. He would never understand the rage she’d felt, four years ago, when M’sieu Petit quietly informed her that Tom had mortgaged all his slaves to obtain money to rebuild the Big House along modern architectural principles: “I’ll be able to purchase the mortgages back within a few years, with profits from the new nail-factory,” Tom had assured her when she’d confronted him. “In any case I would not include you, or any of your family. It is only a business-man’s way of raising money. It’s done all the time.”

Did Patsy know her father had just promised her patrimony to someone else if he couldn’t pay his debts? If he broke his neck taking old Silveret over a fence some day on the mountain, Patsy and Maria would be left with nothing.

But Sally knew, that even without that mortgage, if he broke his neck some afternoon on the mountain, it would make little difference whether her family went to Tom Randolph or to some bank in Richmond. They’d all end up sold and scattered.

By the same token, Tom would never believe that Patsy knew that he was the father of Sally’s children. He would always need to know that he stood first in Patsy’s heart—as she stood first in his. And though he was aware of the many afternoons Tom Randolph spent drinking himself quarrelsome in the Eagle Tavern in Charlottesville, was aware of the young man’s black moods and mercurial temper, he persisted in thinking well of his son-in-law, or at least saying that he did.

He was who he was. He never said he loved her and probably, she reflected wryly, never even thought of their relationship in those terms. But she knew he needed her. As much as the physical desire that was still as warm between them as ever, was his need to know, when he was away, that she would be there when he returned to his home.

He needed to know that he was loved.

He kept even yet the slim bundle of his letters to her, that he’d written on his travels to Rotterdam and The Hague. Sometimes she’d find them slipped behind a clock or under a book, hidden when Patsy interrupted him. He treasured those memories still.

He rose now from where he sat at the side of the cot, went to clasp Sally’s hands briefly—briefly, because Young Tom was there, sitting beside the hearth-fire with a copy of the Richmond Enquirer angled to the glow. Even before their own son they kept a distance, lest talk go around that couldn’t be denied. Very softly he asked, “Shall I send Ursula or Isabel down to help you tonight? He doesn’t seem badly off—”

“It’s early days yet.”

“I shall leave it to your judgment, then, Sally. As we pass through Charlottesville tomorrow I’ll ask Dr. Burns to come see Bev and Mollie. Patsy will be sending me messages—please, you write me, too.”

As they stepped outside into the darkness he kissed her: “Get some sleep if you can. I’m afraid you’ll need it.” Then he strode away up the hill toward the Big House, too preoccupied by his thoughts—of Bev? Of Alexander Hamilton’s plots and machinations? Of James Callendar? Of the election?—to whistle or sing.

If he becomes President, thought Sally, he will be in Philadelphia more—or in that new Federal City on the Potomac. As Mr. Adams’s Vice President, he’d spent as little time in the capital as he could, and Patsy and Randolph had lived a good part of the time on their own plantation at Varina. If he becomes President, will they be back here as they used to, ten months of the year?

The thought, though annoying, didn’t bother her as it once had.

She had done as she’d meant to do: had guaranteed freedom for her children, which was more than her mother had been able to accomplish.

Surely, she thought as she turned back into the dim warm glow of her cabin, that should be enough.

Tom left as soon as it was light enough to see the road down the mountain. He’d knelt in his riding-clothes to kiss bright-haired Annie and burly Jeff, and Sam and Peter Carr hugged their mother breathless and pretended they hadn’t had two of the younger spinning-maids up to their room last night. Patsy held baby Cornelia in her arms, and stood alone half-hidden in the dark of the scaffolding that covered the front of the house; three-year-old Ellen was sickening for a cold, and had remained indoors. Tom Randolph seemed silent and awkward as his father-in-law shook his hand.

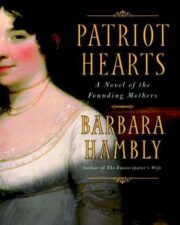

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.