“There grits there, sugarbaby? Mix ’em up with a lot of milk, and pour some honey in. I bet he’ll take a little of that.”

Between them, Young Tom and Sally got the toddler to eat a little, and to drink the bitter willow-bark tea against the fever. When Young Tom had gone back up to the Big House, Sally carried her younger boy over to her mother’s cabin, where Betsie told her that Jenny’s Mollie was worse that morning, and Minerva’s youngest two were showing symptoms as well. Despite all this, and between Sally’s own tasks at the Big House of keeping Tom’s room in order and feeding his three mockingbirds in their cages, she made the time during that day to discreetly scout hiding-places and exit-routes in the woods that could be used that night, if necessary: hiding-places that would accommodate both herself and a three-year-old boy. Young Tom, she knew, was clever enough to escape on his own and rejoin them later.

She came back from one of these scouting expeditions to find both Jeff and Annie Randolph at Betty’s cabin, with another jug of milk pilfered from the kitchen, and some extra blankets. “We heard some of the pickaninnies were sick, ma’am,” explained Annie, glancing worriedly from Betty Hemings’s face to Sally’s, and back. Since Patsy couldn’t very well order her children to shun Sally without an explanation, the golden-haired nine-year-old and her brother had never been told to keep away from her: Like the white children of most plantations, they played with the slave-children and ran in and out of the cabins as cheerfully as if they lived there. “Will they be all right?”

“We’re praying so, sugarbaby,” replied Sally, and smiled down at the girl: Tom’s granddaughter, even if she was Patsy’s child. Only a year older than Maria had been, when Sally and she had set sail for France. Unlike Jeff, she hadn’t yet grown bossy around the slave-children; she would hold the babies with the same grave care that a few years ago she’d devoted to her dolls, practicing to be a mama herself.

Even Jeff seemed cowed in the presence of sickness. To Betty he murmured, “They gonna die?” and he sounded both scared and grieved. He added, stumbling a little on the words, “My baby sister got sick and died. The first Ellen, not Ellen now.” Jeff had been not quite three years old when that fragile little girl had succumbed.

As she watched Tom’s two oldest grandchildren dart back up the slope toward the brick mansion in its tangled cocoon of scaffolding, Sally seemed to hear in her mind the distant clamor of bells ringing the tocsin, of rough voices singing Ça Ira.

She shivered, although the afternoon was warm.

That night Sally dreamed of fire. Dreamed that Paris was burning, that the flames leaped over the customs-barrier and kindled the faubourgs beyond it, and the woods and fields beyond that, fields of tobacco and sugar. The blaze was spreading, and would soon consume the world. Sick with panic, she crouched in the shadow of a wall on the rue St.-Antoine watching the baying mob surge closer and closer, and in the lead walked a woman she knew was her grandmother, the proud black African woman who’d been raped by a sea-captain while on her way to the New World in chains. She carried a torch in one hand, and a pike in the other, and impaled on the pike was the head of Thomas Jefferson.

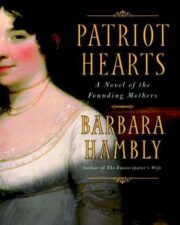

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.