“It is. And you’re Mrs. Adams, if I remember aright, Mrs. Smith’s good mother. I knew when I came home and found that girl of Mrs. Smith’s there, and she told me you’d been sent for as well, I said to myself, ‘Well, there’s one I don’t have to worry will come to harm before I arrive,’ which I’m sorry to say in my business you can’t always count on and that’s the truth.” After a brisk, firm clasp of Abigail’s hand—a welcome change from the upper-class English habit of extending two limp fingers—she turned away at once and began her examination.

“Her waters broke not long after eight, her maid tells me,” Abigail provided, kneeling at Nabby’s other side. “So it’s been—” She glanced at the elaborate little clock that decorated the bedroom’s marble mantel, “—nearly three hours. The pains are about three minutes apart by my watch.”

“Early days yet.” Mrs. Throckle removed the clean towel that covered her basket, and began removing little flasks of olive oil, chamomile, belladonna.

Nabby gave a gasp and a stifled cry, and her hand closed hard on Abigail’s again, her back arching as if it would break. She sobbed, “Ma!” through gritted teeth, and then, desperately, “Papa!” She had been only seven when her youngest brother was born, too young to remain in the house during her mother’s travails, but the knowledge of childbirth’s pain was something it seemed to Abigail that every woman was born understanding. When the contraction was over she clung to Abigail, and shivered, sobbing.

From the street outside the bedroom window Abigail heard the jingle of harness, and rising, angled her head to look down. It was, as she’d half suspected, Nabby’s husband Colonel Smith, just getting into a smart green-and-gold chaise behind a sleek bay gelding. Abigail thought, Damn him, and then, remembering the brandy on his breath as he’d hugged her, Just as well.

“Ma?” Nabby opened her eyes again, struggled to sit a little straighter, to keep her face composed. “Were you afraid? When you had us, I mean, me and Johnny and Charley and Tommy?”

“Of course.” Abigail sat down again beside her. “I think every woman’s afraid, no matter how many times she goes through it safely—as who wouldn’t be?” She rubbed Nabby’s hand, taking comfort, like her daughter, from Mrs. Throckle’s competent bustling presence in the background. “I can assure you, though,” she added, “I was never as afraid having a child as I was crossing the ocean to join your father.”

And Nabby, as Abigail had hoped, blew out her breath in a shaky laugh. Perhaps at the idea of anyone being bothered that much by a sea-voyage—Nabby had been back on her feet and eating heartily within days of boarding the little ship. Perhaps at the idea of her incisive mother being afraid of anything at all.

By the time John’s letter reached her in the fall of ’83, it was too late to embark on the sea. All through the spring of ’84 Abigail made preparations to leave, arranging for the farm to be looked after, and the small rent on the cottage to be collected by John’s brother Peter. Jack Briesler, a veteran who for several years had cut kindling, fixed roofs, and mowed hay at the farm, would go with her, as would Esther Field, the daughter of one of her neighbors, horse-faced, mousy-haired, good-natured, and fifteen. One could not present oneself as the wife of the American Minister to France without servants of some sort, and Abigail wanted to have at least someone around her who could speak English. It was decided that Charley—fourteen now—and twelve-year-old Tommy would remain at the parsonage at Haverhill, fifty miles away near the Vermont border, where her sister Betsey—not an old maid after all—and Betsey’s husband ran a school.

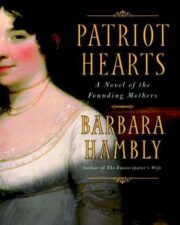

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.