“Will you take this away from me, too?” Her father towered over her mother with both fists raised. “Tell the boys what to do, make the damned starch as well as sell it and spend the money as you think best? Send me off to some corner until you need something else from me?”

“And what am I to do to put bread on the table?” her mother slashed back, in the voice of one goaded beyond all endurance. “It wasn’t I who sent thee off to a corner, ever! That corner where thou hidest half the day and all the night!”

“It is better to dwell in a corner of the house-top, than with a brawling woman in a wide house! There is no place in this house where I can go to get away from the sound of strife! And you, who want to be the man here—”

“I don’t want to be the man! I want thee to be the man!”

“Is that why you let my daughter run after soldiers like a common trull?” He whirled, his face distorted, his finger pointing at Dolley as she stood in the doorway. The blue eyes she remembered with such love stared wildly at her, as if at a stranger. “She is loud and stubborn; her feet abide not in her house: now is she without, now in the streets, and lieth in wait at every corner!” The grip of his hand on her arm nearly pulled Dolley off her feet. Like a rag he shook her in her mother’s face.

“Is that what you will have your daughters come to, woman? To go chasing after the vainglory of the world? Is that why you will be the man of this house? So that you can let them run about the streets like harlots?”

“I beg a thousand pardons, Neighbor Payne.”

John Todd’s stout, sensible shoes creaked on the wooden floor of the shop; his voice was pleasant and soft, as if in a chance encounter outside the meeting-house. “I apologize for bringing thy daughter home later than I told her mother I would; doubly so, for importuning her to go walking with me to begin with. I beg thee to make allowances, for myself and for them both. Both were most kind in indulging my pleas.”

He must have been behind me in the street, thought Dolley. She had had the impression, just before she heard her father’s voice, of quick footfalls hurrying to catch her up. Her eyes thanked him as he concluded, “And now I must go. I should not have come in at all, save that I feared to leave behind me a misunderstanding that would cause strife.”

“No,” said her father uncertainly. “No, you—thou didst right, Neighbor Todd. I knew not…I…I am sorry, Daughter. Molly.” He blinked and held out his hand to his wife, and looking at his face Dolley realized he had not the slightest idea of what he had just said. His cheeks were ashen. “Neighbor Todd, thou wilt stay to dine? We spoke of it, did we not, at Meeting?”

“We did, friend,” John responded. “But the matter was left uncertain, and I would not make extra work for thy good wife.”

Molly Payne was still shaking with anger. In the stairwell door, Dolley was aware of eighteen-year-old Isaac, of Lucy, of the younger children all pressed on one another to listen, frightened and bewildered. It was Mother Amy who said, “I think it will be no great matter to set an extra plate, will it, Mrs. Payne?”

“No,” said Molly Payne, in a voice that sounded to Dolley oddly like her father’s: hesitant, as if she were waking and wasn’t entirely certain where she was. Then, smiling, she went on more strongly, “Thou art entirely welcome, Friend John, and thou knowst it. To dinner, or at any other time.”

Her father was an invisible presence, like a shadow on dinner, and none of the children dared raise their voice or ask what General Washington had looked like.

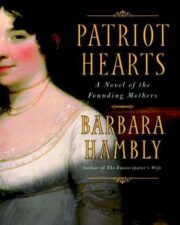

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.