“She was afraid, if she put him out of her bed, that he’d start lyin’ with Iris or Jenny,” Sally’s mother had said, naming the light-skinned housemaid, and the young wife of the plantation cobbler. Both had shown Mr. Jefferson—and a number of his guests at one time or another—their willingness. Being the master’s woman was a good way to get extra food and gifts, and to pass along to any offspring the inestimable gift of preference in an unfair world.

“Why you think she always smiled, and made herself pretty the way she did?” her mother asked. “It’s not just so he wouldn’t fret. It was to draw him back to her, to bind him. To keep him from going away. She’d rather risk death than lose him.”

Sally still thought Mr. Jefferson should have known better. And maybe, she reflected, recalling not only despair but horror in his eyes as fevers, weakness, infections ravaged the beautiful woman he had loved—maybe he had guessed at last what he had so frantically told himself wasn’t true.

On that last morning, on the threshold of autumn of 1782, nine-year-old Sally had been in the room when Miss Patty reached for Mr. Jefferson’s hand and whispered, “Swear to me that you will never give my girls a stepmother.” Miss Patty had had two stepmothers in succession. From what her mother had told her of them, Sally wasn’t surprised that the young woman had been grateful to Betty Hemings for her kindness and for the fact that she’d kept old Jack Wayles from needing to marry a third.

Mr. Jefferson had fainted from grief, and had been carried into the library next to Miss Patty’s room. Everyone went back into the sickroom—Mrs. Eppes and Aunt Carr and Miss Sparling, the young nurse that the doctor from Yorktown had left to care for Miss Patty—but Sally had lingered. She’d looked down at the ravaged unshaven face, the straight red eyelashes like gold against the discolored bruises of sleeplessness. He knows it’s true. He knows that it’s he who killed her by possessing her.

Later she’d overheard some of his friends remark on the excessiveness of his pain, that in those first few weeks he could not even look at his own children without collapsing, and she knew why he couldn’t look at them.

Those things she’d remembered in her days at Eppington, even when her hunger for her family had been at its worst. She’d hated him, when she felt herself going half crazy with longing to be able to read again and when Mrs. Eppes came up with extra tasks and duties in the kitchen and the scullery to “un-spoil” a slave she considered inattentive and uppity. Yet she never could hate him with the whole of her heart.

In time her anger had altered, changed to a kind of slow-burning frustrated grief. For she knew that all things were the way all things were.

She had come to love Polly, and sunny-hearted baby Lucie, as if they were her own sisters. Mrs. Eppes had a baby daughter named Lucie as well: Polly would braid ribbons of identical color into both toddlers’ hair, and say the Lucies were her own twin babies.

Then in early October of 1784, shortly after Mr. Jefferson left for France with Patsy, whooping cough swept over Eppington Plantation.

Both little Lucies died.

“Mesdemoiselles, les voilà!” M’sieu Petit nudged his horse up close to the chaise window, bent from the saddle, and pointed through the trees with his quirt. “Les murailles de Paris. How you say…?” He mislaid the English word, and shook his head with a wry smile, but pride and happiness sparkled in his eyes. Then he simply explained, “Paris.”

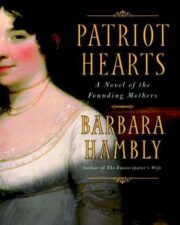

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.