Sometimes, she was almost certain, Jimmy got to the drawer before she did.

She moved the iron bolts of the kitchen door, slipped it open barely the eight inches that would admit her body, then closed it softly again. She paused long enough to slip her feet into the pattens that protected her shoes from the black, acid Paris mud, then tucked her small bundle of belongings more firmly under her arm. At this hour, she should be fairly safe. Even rioters had to sleep sometime.

Still she felt breathless as she walked in the hushed stillness beneath the chestnut trees. The kitchen-boy had told her yesterday that while the rioting was going on in the Étoile, the lawyers and merchants who’d elected the representatives to the National Assembly had declared themselves a Governing Committee, and had called for forty-eight thousand militiamen to keep order and deal with the royal troops camped in the Bois de Boulogne and the vegetable-farms around Montmartre and Rambouillet, should they attack.

A glorious time to be alive.

Everything will be all right.

Desperately, Sally hoped so. Whatever was happening in Paris, it was going to be her home henceforth.

When Mr. Jefferson had said last November that he had asked to return to the United States for a short visit, to take Patsy and Polly home, Jimmy had announced that he would not return with them. As slavery did not exist in France, he declared, he was a free man, free to go or to stay. And he chose to stay.

Jefferson had answered, with cool reasonableness, that as Jimmy was a free man he must accept a free man’s responsibilities, among them not robbing the man who had brought him to France and was paying for him to be taught the skills of French cookery by which he intended to make his living. Jimmy owed it to his former master—Tom’s voice had gritted over the word—to return to Virginia for as long as it would take him to train a replacement there. Then he would be free to go wherever he wished.

Sally had seen that for all the calm rationality of his answer, Tom was furious.

He’s a white Virginia gentleman. Sally quickened her step between the chestnut trees, the half-seen pale blocks of great houses set back from the road in their parklike grounds. Whatever he might write, or think, or say about the Rights of Man and the injustice of slavery, what he feels is what he feels.

It was this dichotomy, this yawning gulf between his ideals and the demands of his flesh, that had made him turn away from her, all those months.

Wanting her in spite of every inner vow he had made to himself, the promise not to be the kind of master who would force a slave-girl.

Even at fifteen, turning from girl to woman, she had seen that in his eyes.

Within a week of her arrival with Sally in Paris, Polly had gone into a convent-school. She and Patsy would come home on Sundays, to spend the afternoon and the night in their father’s house and return to the Abbaye Royale de Panthemont in the morning, and on those nights Sally would sleep in a cubicle just off the girls’ bedroom. Mr. Jefferson was strict with Sally, forbidding her to go about the streets by herself. In Williamsburg, and in Richmond, she knew instinctively the kinds of places it was safe for a young girl to go, and in Williamsburg she knew, too, that any black woman, and most black men, would be her friend in a difficult situation.

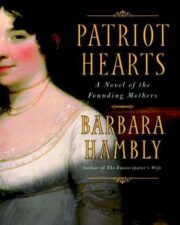

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.