Mr. Jefferson had assigned M’sieu Petit the task of teaching Sally the finer skills of service, how to clean and mend and care for fine clothing, how to pack it loosely in paper and straw to be stored in trunks in the attic til it was wanted. How to starch and iron ruffles, and how to dress hair. Miss Patty herself had taught Sally the art of fancy sewing; the little Frenchman clicked his tongue approvingly, and put her to study with Mme. Dupré, the household seamstress and laundrywoman, the only female in the masculine establishment.

But these things didn’t take up all Sally’s days. When Polly went off to the convent, Sally asked, a little timidly, if she might read in the library while Mr. Jefferson was out. “Mr. Adams would let me, sir. You can write and ask him, if I ever tore or damaged anything, or didn’t put it back.”

To her surprise Mr. Jefferson replied, “Of course you may, Sally. Even when you were quite a little girl I remember you were always careful with books.”

She hadn’t thought he’d noticed.

It was his library that brought them together—his library, and Sally’s unquenchable curiosity about everything and anything. She picked up kitchen-French quickly, and the slurry argot of the cab-men, street-singers, and vendors of ratbane and brooms. But Mr. Jefferson hired a French tutor for both her and Jimmy. And often in the evenings, if he wasn’t invited out to dine, Mr. Jefferson would take an hour to help her read the French of good books. More than once, having left her in the library deep in Mr. Pope’s Iliad or some article in Diderot’s Encyclopédie, he would return late to find her still there, reading by candlelight while the rest of the house slept.

Much of the time he’d be with Mr. Short, his secretary from Virginia who also had a room in the attic of the Hôtel Langeac, or Mr. Humphreys, another semipermanent Virginian guest. But Mr. Humphreys had his own friends among the Americans in Paris, and Mr. Short was having an affair with a society lady. On many nights Mr. Jefferson would return, a little bemused, alone. Then if Sally was still in the library he’d bring a chair over next to hers, and they’d talk about the marvels described in the Encyclopédie, or he’d tell her the gossip that everyone traded in the Paris salons. Sometimes he’d play his violin for her, though his broken wrist was slow to heal, and the music that gave him such joy was also now a source of pain. Sally guessed that without his daughters during the week he was lonely. For a man as gregarious as he was, there was a part of him that needed his family; that needed faces familiar to him from home.

And in a sense, she and Jimmy were family. She had known Mr. Jefferson since the age of two, and thought no more of being alone with him at midnight, while all the household slept, than she would have thought of staying up late talking to one of her old uncles on the cabin step of the quarters along Mulberry Row.

Jimmy, who’d started out teasing her about getting wrinkles from too much reading, sometimes looked at her with that calculating glance and said, “No, you stay up however late you want, Sal. You learn lots of things, reading.”

She hadn’t known what he was getting at, at first. In that first year in Paris, so enchanted had she been with that whole glittering city that she’d barely been aware of the changes in her body.

She was used to people telling her she was pretty, and used to men—both black and white—trying to steal kisses. From the age of twelve Sally had been adept at defending herself with nails and knees from would-be swains in the quarters. And like any female slave from that age up, she had learned the risky maneuvers involved in saying No to white men without being punished for insolence.

She was aware that she was getting taller. She knew her hips had widened, and her breasts filled out, because just before her first Christmas in France, soon after her fifteenth birthday, she’d overheard Mr. Short remark to Jefferson, “By gad, Jefferson, that girl of yours is growing into a beauty.” Not long after that Jimmy had taken her aside and said, “Now, you don’t let those good-for-nothing footmen down in the kitchen go sweet-talkin’ you into lettin’ ’em kiss you, girl,” and Sally had only stared at him in disbelief.

“I ain’t that fond of garlic,” she’d retorted, and Jimmy laughed.

But he’d sobered quickly, and said, “You be gettin’ more’n a tongue full of garlic, if you let ’em catch you alone. You remember, girl, you in France now. You and me, we’re free here. There’s no law here that says a black girl can’t scratch a white man’s face if he puts his hand up her skirt.”

“And how many times you had your face scratched, brother?”

“Enough to know.”

Jefferson apparently shared Jimmy’s concerns. The following March—1788—when he went to Amsterdam to meet Mr. Adams and sign a treaty with the Dutch, he arranged for Sally to board with the seamstress Mme. Dupré and her husband rather than stay in the Hôtel Langeac with the other servants. Sally had romped with Mme. Dupré’s grandchildren and helped Madame and her daughter in the kitchen. At the market one morning there she had encountered Sophie Sparling, who had helped nurse poor Miss Patty in her final months. Twenty-two now, Sophie was a paid companion to a Mrs. Luckton, an English widow who lived in the nearby rue des Lesdiguères.

Things were indeed different in Paris. Here, one wasn’t immersed in a world of slaves and slaveholders. She had seen in the way Mr. Jefferson spoke to her, that with her fair complexion and long, silky hair, he sometimes almost forgot that her grandmother had been African. Maybe because she knew herself to be legally free, she found herself shedding the barriers of caution that existed between slaves and masters. Here, he could no longer give her away, or send her where she didn’t wish to go.

Somehow, in Paris, it didn’t matter that Sophie Sparling was the white granddaughter of a tobacco-planter, and Sally Hemings the not-quite-white granddaughter of an African woman who’d been enslaved and raped. It was good to speak English to another woman who remembered Virginia’s green hills. A little to Sally’s surprise, Sophie seemed to think so, too.

Looking back now on those weeks at Mme. Dupré’s, Sally felt a desperate longing for the simplicity she’d known then.

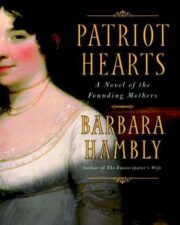

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.