That’s how I want to live, she thought, as she hurried down the thinning gray gloom of the Champs-Elysées. In a little house like that, just a couple of rooms that’ll be my own.

And she shivered, though the dawning day was already scorching hot.

Around her, the city seemed eerily still. The big houses set along the fashionable avenue were dark, shutters closed tight. But as she approached the open expanse of the Place Louis XV, she could see men clustered in the wine-shops under the colonnade, muttering and waving their arms.

Saturday—the day before yesterday—men and women had poured into the huge square to protest the King’s dismissal of his Finance Minister M’sieu Necker, who—everyone in the kitchen said—was the only man capable of ending the famine and financial mess that had held the country in the grip of death for a year. Cheap pamphlets—commissioned by Necker’s salonnière wife—praised his skills, and vomited scatalogical invective on the men the King had selected to replace him.

The demonstrators had been met by a regiment of hired German soldiers, under the command of a cousin of the Queen’s.

Dried blood still smeared the cobblestones, dark under a blanket of dust and drawing whirling clouds of flies.

Sally lowered her head and cut through a corner of the square, with barely a glance at the equestrian statue of a former King, now smeared with dung and garbage. Another day she would have walked through the Tuileries gardens rather than along the quais at the riverside, for the river stank like a sewer. But she felt uneasy about going into those aisles of hedges and trees. Men roved the streets and alleyways of Paris these days, men out of work and hungry—angry, too. With the shortages of bread, the tangled national finances that were driving more and more men out of employment, there were fewer who could pay for servants, barbers, new clothes, new shoes, food.

As she hurried along the dark quais, Sally could glimpse them: long dirty hair, baggy trousers, bare legs, the wooden shoes of peasants. Some moved about the garden, others slept beneath its trees.

Everything will be all right.

She felt sick with fright.

Those days at Mme. Dupré’s, those days of walking about the city with Sophie, seemed to her now like the last time that her life had been normal: that she had been herself, her real self. When Sophie could get away from her employer, which was seldom—Mrs. Luckton was worse than any plantation mistress—they would rove together through the gardens of the Luxembourg and the Tuileries, or wander among the exceedingly expensive shops of the Palais Royale. They’d pretended to shop for silks of the most newly fashionable hues—“flea’s thigh” and “goose-turd green”—and admired the jeweled rings and watches—or whole coffee-sets or sewing-kits or travelers’ writing desks of enamel and gold—at Le Petit Dunkerque.

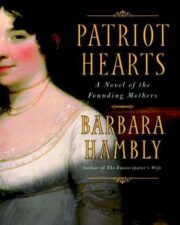

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.