She shrugged, barely showing any interest. "It doesn't surprise me. I told you what Daphne was capable of doing, but you just don't listen. You think the world's all birds and roses. She's going to cut back plenty on what we get too. You'll see," she said. She wheeled herself closer and lowered her voice to a whisper. "It's better that we stay here rather than return to Greenwood. Put your brilliant mind and your time to figuring out a way to get her to let us stay," she said.

"Let us stay?" I laughed so madly I even frightened myself. "She can't stand the sight of us. You're the one who's dwelling in a world of illusion if you think Daphne would even consider having us around now."

"Well, that's just great," Gisselle moaned. "You just want to give up?"

"It's the way it is," I said with a tone of fatalism that shocked her. She remained there staring in at me as if she expected me to snap out of my mood and tell her the things she wanted to hear.

"Aren't you going to get washed and dressed for the wake?" she finally asked.

"Because I disobeyed Daphne and went to the institution to see Uncle Jean, I am not permitted to go to the wake. I'm being punished."

"Can't go to the wake? That's your punishment? Why can't I be punished too?" she cried.

I spun around on her so abruptly she wheeled herself back.

"What's wrong with you, Gisselle? Daddy loved you."

"He did until you arrived. Then he practically forgot about me," she moaned.

"That's not true."

"It is, but it doesn't matter anymore. Oh well," she said, sighing deeply and fluffing her hair. "Someone's got to entertain Beau when he arrives. I guess I'll fill in." She smiled and rolled herself back to her room.

I got up and gazed out the window, wondering if I wouldn't be better off just running away. I might have seriously considered it if I didn't recall some of the promises I had made to Daddy. I had to remain here to look after Gisselle, as best I could, to succeed at my art and become a credit to his memory. Somehow, I would overcome the obstacles Daphne was sure to place in my path, I vowed, and some day I would do just what she had said I would do: I would help Uncle Jean.

I returned to my bed and lay there thinking and dozing off until I heard Gisselle go to the stairway and have Edgar help her down to attend the wake. Then I got down on my knees and recited the prayers I would have recited at Daddy's coffin.

Martha brought up a tray of food for me, and even though she had explicit orders from Nina commanding me to eat, I just picked and nibbled, my appetite gone, my stomach too tight and nervous to accept much more.

Hours later, I heard a gentle knock on my door. I was lying there in the dark, with just the moonlight spilling through my window illuminating the room. I leaned over, flicked on a lamp, and told whoever it was to enter. It was Beau, with Gisselle right behind him.

"Daphne doesn't know he's up here," she said quickly, a capricious smile on her face. How she so enjoyed doing forbidden things, even if it meant doing something for me. "Everyone thinks he's wheeling me around the house. There are so many people here, we won't be missed. Don't worry."

"Oh Beau, you'd better not stay here. Daphne threatened to bring your parents to the house and get you in trouble because you drove me to the institution," I warned.

"I'll risk it," he said. "Why was she so angry anyway?"

"Because I found out what she had done to my uncle," I said. "That's the main reason."

"It's so unfair for you to suffer anything at this time," he said, and our eyes locked for a moment.

"I could leave you two alone for a while," Gisselle suggested when she saw the way we were gazing at each other. "I'll even go to the top of the stairway and be a love sentry."

I was about to protest, when Beau thanked her. He closed the door softly and came to sit beside me on the bed and put his arm around my shoulders.

"My poor Ruby. You don't deserve this." He kissed my cheek. Then he looked around my room and smiled. "I remember being in here once before . . . when you tried some of Gisselle's pot, remember?"

"Don't remind me," I said, smiling for the first time in a long time. "Except I do remember you were a gentleman and you did worry about me."

"I'll always worry about you," he said. He kissed my neck and then the tip of my chin before bringing his lips to mine.

"Oh Beau, don't. I feel so confused and troubled right now. I want you to kiss me, to touch me, but I keep thinking about why I am here, the tragedy that has brought me back."

He nodded. "I understand. It's just that I can't keep my lips off you when I'm this close," he said.

"We'll be together again and soon. If you don't get up to Greenwood during the next two weeks, I'll see you when we return for the holidays."

"Yes, that's true;" he said, still holding me close to him. "Wait until you see what I'm getting you for Christmas. We'll have great fun, and we'll celebrate New Year's together and—"

Suddenly the door was thrust open and Daphne stood there, glaring in at us.

"I thought so," she said. "Get out," she told Beau, holding up her arm and pointing.

"Daphne, I . . . ″

"Don't give me any stories or any excuses. You don't belong up here and you know it.

"And as for you," she said, spinning her gaze at me, "this is how you mourn the death of your father? By entertaining your boyfriend in your room? Have you no sense of decency, no self-control? Or does that wild Cajun blood run so hot and heavy in your veins, you can't resist temptation, even with your father lying in his coffin right below you?"

"We weren't doing anything!" I cried. "We—"

"Please, spare me," she said, holding up her hand and closing her eyes. "Beau, get out. I used to think a great deal more of you, but obviously you're just like any other young man . . . You can't pass up the promise of a good time, no matter what the circumstances."

"That's not so. We were just talking, making plans."

She smiled icily. "I wouldn't make any plans that included my daughter," she said. "You know how your parents feel about your being with her anyway, and when they hear about this . . ."

"But we didn't do anything," he insisted.

"You're lucky I didn't wait a few more moments. She might have had you with your clothes off, pretending to be drawing you again," she said. Beau flushed so crimson I thought he would have a nosebleed.

"Just go, Beau. Please," I begged him. He looked at me and then started for the door. Daphne stepped aside to let him pass. He turned to look back once more and then shook his head and hurried away and down the stairs. Then Daphne turned back to me.

"And you almost broke my heart down there before, pleading to have me let you attend the wake . . . like you really cared," she added, and closed the door between us, the click sounding like a gunshot and making my heart stop. Then it started to pound and was still pounding when Gisselle opened the door a few moments later.

"Sorry," she said. "I just turned my back for a moment to get something, and the next thing I knew, she was charging up the stairs and past me."

I stared at her. It was on the tip of my tongue to ask if the truth wasn't that she really had made herself quite visible so Daphne would know she and Beau had come up, but it didn't matter. The damage was done, and if Gisselle was responsible or not, the result was the same. The distance between Beau and me had been stretched a little farther by my stepmother, who seemed to exist for one thing: to make my life miserable.

Daddy's funeral was as big as any funeral I had ever seen, and the day seemed divinely designed for it: low gray clouds hovering above, the breeze warm but strong enough to make the limbs of the sycamores and oaks, willows and magnolias wave and bow along the route. It was as if the whole world wanted to pay its last respects to a fallen prince. Expensive cars lined the streets in front of the church for blocks, and there were droves of people, many forced to stand in the doorway and on the church portico. Despite my anger at Daphne, I couldn't help but be a little in awe of her, of the elegant way she looked, of the manner in which she carried herself and guided Gisselle and me through the ceremony, from the house to the church to the cemetery.

I wanted so much to feel something intimate at the funeral, to sense Daddy's presence, but with Daphne's eyes on me constantly and with the mourners staring at us as if we were some royal family obligated to maintain the proper dignity and perform according to their expectations, I found it hard to think of Daddy in that shiny, expensive coffin. At times, even I felt as if I were attending some sort of elaborate state show, a public ceremony devoid of any feeling.

When I did cry, I think I cried as much for myself and for what my world and life would now be without the father Grandmère Catherine had brought back to me with her final revelations. This precious gift of happiness and promise had been snatched away by jealous Death, who always lingered about us, watching and waiting for an opportunity to wrench us away from all that made him realize how miserable his own destiny was eternally to be. That was what Grandmère Catherine had taught me about Death, and that was what I now so firmly believed.

Daphne shed no tears in public. She seemed to falter only twice: once in the church, when Father McDermott mentioned that he had been the one to marry her and Daddy; and then at the cemetery, just before Daddy's body was interred in what people from New Orleans called an oven. Because of the high water table, graves weren't dug into the ground, as they were in other places. People were buried above ground in cement vaults, many with their family crests embossed on the door.

Instead of sobbing, Daphne brought her silk handkerchief to her face and held it against her mouth. Her eyes remained focused on her own thoughts, her gaze downward. She took Gisselle's and my hand when it was time to leave the church, and once again when it was time to leave the cemetery. She held our hands for only a moment or two, a gesture I felt was committed more for the benefit of the mourners than for us.

Throughout the ceremony, Beau remained back with his parents. We barely exchanged glances. Relatives from Daphne's side of the family stayed closely clumped together, barely raising their voices above a whisper, their eyes glued to our every move. Whenever anyone approached Daphne to offer his or her final condolences, she took his hands and softly said "Merci beaucoup." These people would then turn to us. Gisselle imitated Daphne perfectly, even to the point of intoning the same French accent and holding their hands not a split second longer or shorter than Daphne had. I simply said "Thank you," in English.

As if she expected either Gisselle or me to say or do something that would embarrass her, Daphne observed us through the corner of her eye and listened with half an ear, especially when Beau and his parents approached us. I did hold onto Beau's hand longer than I held onto anyone else's, despite feeling as if Daphne's eyes were burning holes in my neck and head. I was sure Gisselle's behavior pleased her more than mine did, but I wasn't there to please Daphne; I was there to say my last goodbye to Daddy and thank the people who really cared, just as Daddy would have wanted me to thank them: warmly, without pretension.

Bruce Bristow remained very close by, occasionally whispering to Daphne and getting some order from her. When we had arrived at the church, he offered to take my place and wheel Gisselle down the church aisle. He was there to wheel her out and help get her into the limousine and out of it at the cemetery. Of course, Gisselle enjoyed the extra attention and the tender loving care, glancing up at me occasionally with that self-satisfied grin on her lips.

The highlight of the funeral came at the very end, just as we were approaching the limousine for our ride home. I turned to my right and saw my half brother, Paul, hurrying across the cemetery. He broke into a trot to reach us before we got into the car.

"Paul!" I cried. I couldn't contain my surprise and delight at the sight of him. Daphne pulled herself back from the doorway of the limousine and glared angrily at me. Others nearby turned as well. Bruce Bristow, who was preparing to transfer Gisselle from her chair into the car, paused to look up when Gisselle spoke.

"Well, look who's come at the last moment," she said.

Even though it had only been months, it seemed ages since Paul and I had seen each other. He looked so much more mature, his face firmer. In his dark blue suit and tie, he appeared taller and wider in the shoulders. The resemblances in Paul's, Gisselle's, and my face could be seen in his nose and cerulean eyes, but his hair, a mixture of blond and brown—what the Cajuns called chatin—was thinner and very long. He brushed back the strands that had fallen over his forehead when he broke into a trot to reach me before

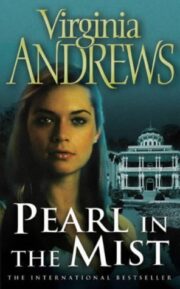

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.