"You two are going to enjoy attending school in Baton Rouge," Daddy said, flicking a gaze at us in his rearview mirror.

"I hate Baton Rouge," Gisselle replied quickly.

"You were really there only once, honey," Daddy told her. "When I took you and Daphne there for my meeting with the government officials. I'm surprised you remember any of it. You were only about six or seven."

"I remember. I remember I couldn't wait to go home."

"Well now you'll learn more about our capital city and appreciate what's there for you. I'm sure the school will have excursions to the government buildings, the museums, the zoo. You know what the name 'Baton Rouge' means, don't you?" he asked.

"In French it means 'red stick'," I said.

Gisselle glared. "I knew that too. I just didn't say it as quickly as she did," she told Daddy.

"Oui, but do you know why it's called that?" I didn't and Gisselle certainly had no idea, nor did she care. "The name refers to a tall cypress tree stripped of its bark and draped with freshly killed animals that marked the boundary between the hunting grounds of the two Indian tribes at the time," he explained.

"Peachy," Gisselle said. "Freshly killed animals, ugh."

"It's our second-largest city and one of the country's largest ports."

"Full of oil smoke," Gisselle said.

"Well, the hundred miles or so of coastline to New Orleans is known as the Petrochemical Gold Coast, but it's not just oil up here. There are great sugar plantations too. It's also called the Sugar Bowl of America."

"Now we don't have to attend history class," Gisselle said.

Daddy frowned. It seemed he could do nothing to cheer her up. He looked at me and I winked, which made him smile.

"How did you find this school anyway?" she suddenly inquired. "Why couldn't you find one closer to New Orleans?"

"Daphne is the one who found it, actually. She keeps up on this sort of thing. It's a highly respected school and it's been around for a long time, with a long tradition of excellence. It's financed through donations and tuition from wealthy Louisianans, but mainly from an endowment granted to it from the Clairborne family through its sole surviving member, Edith Dilliard Clairborne."

"I bet she's a dried-up hundred-year-old relic," Gisselle said.

"She's about seventy. Her niece Martha Ironwood is the chief administrator. What you would call the principal. So you see, you're right in what we call the rich old Southern tradition," Daddy said proudly.

"It's a school without boys," Gisselle said. "We might as well check into a nunnery."

Daddy roared with laughter. "I'm sure it's nothing like that, honey. You'll see."

"I can't wait. This is such a long, boring ride. Put on the radio at least," Gisselle demanded. "And not one of those stations that play that Cajun music. Get the top forties," she ordered.

Daddy did so, but instead of brightening her outlook it lulled her to sleep, and for the remainder of the trip, Daddy and I had some quiet conversations. I loved it when he was willing to tell me about his trips to the bayou and his romance with my mother.

"I made a lot of promises to her that I couldn't keep," he said regretfully, "but one promise I will keep: I will see that you and Gisselle have the best of everything, especially the best opportunities. Of course," he added, smiling, "I didn't know you existed. I've always thought your arrival in New Orleans was a miracle I didn't deserve. No matter what's happened since," he added pointedly.

How I had come to love him, I thought as my eyes watered with happy tears. It was something Gisselle couldn't understand. More than once she had tried to get me to hate our father. I thought it was because she was jealous of the relationship that had quickly developed between us. But she was forever reminding me that he had deserted my mother in the bayou after he had made her pregnant while he was married to Daphne. Then he compounded his sins by agreeing to let his father purchase the baby.

"What kind of a man does such a thing?" she would ask, stabbing at me with her questions and accusations.

"People make mistakes when they're young, Gisselle."

"Don't believe it. Men know what they're doing and what they want from us," she'd said with her eyes small, the look cynical.

"He's been sorry about it ever since," I had said. "And he's trying to do what he can to make up for it. If you love him, you will do whatever you can to make his suffering less."

"I am," she'd said joyfully. "I help him by getting him to buy me whatever I want whenever I want it."

She's incorrigible, I thought. Not even Nina and one of her voodoo queens could recite a chant or find a powder to change her. But someday, something would. I felt sure of that; I just didn't know what it would be or when.

"There's Baton Rouge ahead," Daddy announced some time later. The spires of the capitol building loomed above the trees in the downtown area. I saw the huge oil refineries and aluminum plants along the east bank of the Mississippi. "The school is higher up, so you'll have a great view."

Gisselle woke up when he turned off the Interstate and took the side roads, passing a number of impressive-looking antebellum homes that had been restored: two-story mansions with columns. We passed one beautiful home that had Tiffany glass windows and a bench swing on the lower galerie. Two little girls were on it, both with golden brown pigtails and dressed in identical pink dresses and black leather saddle shoes. I imagined they were sisters, and my mind started to create a fantasy in which I saw myself and Gisselle growing up together in such a home with Daddy and our real mother. How different it all could have been.

"Just a little farther," Daddy said and nodded toward a hill. When he made another turn, the school came into view. First we saw the large iron letters spelling out the word GREENWOOD over the main entrance, which consisted of two square stone columns. A wrought-iron fence ran for what looked like acres to the right and to the left. I saw some buttonbush along the foot of the fence, its dark green leaves gleaming around the little white balls of white. Along a good deal of the fence were vines of trumpet creepers with orange blossoms.

From both sides of our car we could see rolling green lawns and tall red oak, hickory, and magnolia trees. Gray squirrels leapt gracefully from branch to branch as if they could fly. I saw a red woodpecker pause on a branch to look our way. There were stone walkways with short hedges and fountains everywhere, some with little stone statues of squirrels, rabbits, and birds.

An enormous garden led to the main building--rows and rows of flowers, tulips, geraniums, irises, golden trumpet roses, and tons of white, pink, and red impatiens. Everything looked trimmed and manicured. The grass was so perfect it looked cut by an army of grounds workers armed with scissors. Not a branch, not a leaf, nothing appeared out of place. It was as if we had ventured into a painting.

Above us the main building loomed. It was a two-story structure of antique brick and gray-painted wood. Dark green ivy vines worked their way up around the brick to frame the large panel windows. A wide stone stairway led up to the large portico and great front doors. There was a parking lot to the right with signs that read RESERVED FOR FACULTY and RESERVED FOR VISITORS. Right now the lot was nearly full of cars. There were parents and young girls meeting and greeting each other, old friends obviously renewing friendships. It was an explosion of excitement. The air was full of laughter, the faces full of smiles. Girls hugged and kissed each other, and all began talking at once.

Daddy found a spot for us and the van, but Gisselle was ready to pounce with a complaint.

"We're too far from the front, and how am I supposed to get up that stairway every day? This is horrible."

"Just hold on," Daddy said. "They told me there is an approach built for people in wheelchairs."

"Great. I'm probably the only one. Everyone will watch me being wheeled up every morning."

"There must be other handicapped girls here, Gisselle. They wouldn't build an entryway just for you," I assured her, but she just sat there scowling at the scene unfolding before us.

"Look. Everyone knows everyone else. We're probably the only strangers at the school."

"Nonsense," Daddy said. "There's a freshman class, isn't there?"

"We're not freshmen. We're seniors," she reminded him curtly.

"Let me go find out how to proceed first," Daddy said, opening his door.

"Proceed home, that's how," Gisselle quipped. Daddy waved to our van driver, who pulled up alongside our car. Then he went to speak to a woman in a green skirt and jacket who was holding a clipboard.

"All right," Daddy said, returning. "This is going to be easy. The gangway is off right there. First you go to registration, which is being held in the main lobby, and then we'll go to the dormitory."

"Why don't we go to the dormitory first?" Gisselle demanded. "I'm tired."

"I was told to bring you here first, honey, so you can get your information packet about your classes, a map of the grounds, that sort of thing."

"I don't need a map of the grounds. I'll be in my room all the time, I'm sure," Gisselle said.

"Oh, I'm sure you won't," Daddy replied. "I'll get your chair out, Gisselle."

She pressed her lips together and sat back with her arms folded tightly under her bosom. I got out. The sky was crystalline blue and the clouds were puffy and full, looking like cotton candy. There was a magnificent view of the city below and beyond, a view of the Mississippi River with its barges and boats moving up and down. I felt like we were on top of the world.

Daddy helped Gisselle into her chair. She was stiff and uncooperative, forcing him to literally lift her. When she was situated in it, he started to wheel her toward the gangway. Gisselle kept her gaze ahead, her face twisted in a smirk of disapproval. Girls smiled at us and some said hello, but Gisselle pretended not to see or hear.

The gangway took us through a side entrance into the wide main lobby. It had marble floors and a high ceiling, with great chandeliers and a large tapestry depicting a sugar plantation on the far-right wall. The lobby was so large the voices of the girls echoed in it. They were all standing in three long lines, which line they were in depending on the first initial of their last names. The moment Gisselle set eyes on the crowd, she moaned.

"I can't sit here like this and wait," she complained loudly enough for a number of girls nearby to overhear. "We don't have to do this at our school in New Orleans! I thought you said they knew about me and would take my problems into consideration."

"Just a minute," Daddy said softly. Then he went to speak to a tall thin man in a suit and tie who was directing the girls into the proper lines and helping them to fill out some forms. He looked our way after Daddy spoke to him, and a moment later he and Daddy went to the desk upon which was the sign A-H. Daddy spoke to the teacher behind our desk, and she then gave him two packets. He thanked her and the tall man and quickly returned to our side.

"Okay," Daddy said, "I've got your registration folders. You're both assigned to the Louella Clairborne House."

"What kind of name for a dorm is that?" Gisselle said.

"It was named after Mr. Clairborne's mother. There are three dorms, and Daphne assured me that you two are in the best of the three."

"Great."

"Thank you, Daddy," I said, taking my packet from him. I felt guilty getting the preferential treatment along with Gisselle and avoided the jealous gazes of the other girls who were still waiting in line.

"Here's your packet," Daddy said. He put it into Gisselle's lap when she didn't reach for it. Then he turned her around and wheeled her out of the building.

"They told me there's an elevator to get you up and down in the main building. The bathrooms all have facilities for handicapped people, and your classes are all pretty much on the same floors so you won't have great difficulty getting from one to the other in time," Daddy said.

Reluctantly, Gisselle opened the packet as we descended the gangway. On the first page was a letter of welcome from Mrs. Ironwood, strongly advising that we read each and every page of the orientation materials and concern ourselves especially with the rules.

Two of the dormitories were located in the rear and to the right and the third dorm, our dorm, was located in the rear to the left. As we drove slowly around the main building toward our dorm, I gazed down the slope and saw the boathouse and the lake. A solid layer of water hyacinth stretched from bank to bank, their lavender blossoms pale with a dab of yellow on the center petals, surrounded by light green leaves. The water of the lake shone like a polished coin.

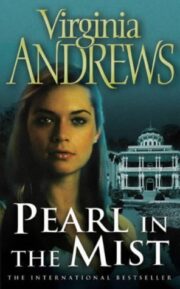

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.