Heinrich Geist is a large, bewhiskered man, younger and stouter than I’d imagined. Under caterpillar eyebrows, his eyes are blunt as bullets. I imagine those eyes staring at us now through his camera lens, and a chill creeps up the back of my neck.

Crammed onto one side of the gravy-brown love seat in Geist’s sunlit parlor, which serves as his studio, with the perfume of Aunt Clara’s oiled ringlets sticky in the air, I wish I’d had a bite to eat this morning. But I’d simply been too nervous. I was ten years old the last time I sat for a formal photograph. Even now I can almost feel the press of Toby’s hand slipped into mine, for comfort.

“Chin up,” he’d told me. “A weak chin is the sign of a traitor.”

“Another minute,” commands Geist, his voice muffled under the drop cloth.

I hold my chin high.

Standing behind me, Quinn exhales through his nostrils, signaling his displeasure.

Today is January the eighteenth in the new year of 1865. “A significant date,” Geist had assured us as he’d ushered us into his sunny parlor, “for communing with our departed.”

Quinn had snorted at that, too.

“Your folly surprises me,” my cousin had rebuked when I’d first approached him. “Photographers are opportunists. Like cockroaches on the battlefield, scurrying for their capital on the dead.

A boy’s face for sale to his grieving family makes a tidy profit.”

“Mr. Geist is more than a photographer. He is a medium.” I’d shown Quinn the business card Geist had enclosed with his reply to my letter. “And Father’s friends at the Swedenborgian church aren’t charlatans they were kind to me when I asked about Mr. Geist. I’m sure he’ll be a gentleman as well.”

“Perhaps.” Quinn’s lips had tightened to signal his doubt. “But most mediums are frauds who’d steal the pennies off a dead man’s eyes.”

“Yet the movement has believers,” I’d insisted. “And Mr. Geist writes in his letter that the more family I bring, the better our luck. Come with us, please?”

“It’s nonsense that Mother and Father agreed to such claptrap. But I’ll do it for you, Jennie. Know that.” His silver eyes had been steady on mine, and in a tingling moment I knew that Quinn hadn’t forgotten that kiss after all.

Blushing, I’d dropped my eyes to study the laces on my shoes. “Thank you, Cousin.”

In the end, I rationalized, he’d probably relented only to relieve his boredom. There are only so many trips around a garden that a young man can make. I hoped it was a good sign that Quinn was looking to become more sociable again.

My own reservations have more to do with money. Five dollars seems like an extravagance for a single portrait seating, and Geist had requested that we pay five more when we are delivered a photograph. I can’t help but think of the warm winter cloak, new hat, and boots I could have enjoyed for the same price.

Services will be Promptly rendered, but with no Assurance of Spiritual

Communication, Geist had clarified in his letter.

But this first attempt at spiritual communication is anything but otherworldly. My eyes itch, while my face is stiff as a cold caramel. Only a few minutes have gone by, but it feels like an eternity.

“Persevere, family,” Geist intones. “William Pritchett is close at hand.”

Will has never seemed so far away. He’d laugh to see us now. How fascinated he’d be with Geist’s instrument and tripod. What amusement he’d take in Aunt, who holds one of his Harvard photographs balanced upright on her plump knees.

According to Geist, the photograph provides passage for Will’s spirit to enter this gathering of Aunt Clara, Uncle Henry, Quinn, and me. “The deceased are drawn to their loved ones like butterflies to sugar water. Our beloved often appear to us through vapor or mist,” Geist had clarified. “Other times, another passed soul such as an angel or a Native Indian is sent to serve as messenger.”

This had provoked a dramatic gasp from Aunt Clara, who has a fondness for angels.

Now Geist jumps out from under the muslin drape and darts around to the front of the camera.

“Oh, dear. Is something broken?” squeaks Aunt through gritted teeth.

“Not at all.” Geist fits the cap on the lens then slides a rectangular plate into the body of the instrument. “Exposure to the light is crucial to our success. But now we’re finished. I have cut the light. The butterfly is in the net, so to speak. You are free to move. I feel certain that

William Pritchett was with us! Did you sense it?” His eyes rove the room as if following a starling. Then he slips behind the camera and removes a wooden box, the same dimensions of the plate, from its body.

Geist then hands the contraption to his waiting housemaid, who scurries off with it at once.

“A most confounded thing,” declares Uncle Henry, “but I experienced a tickling in my fingers.”

“A chill down my neck, perhaps,” Aunt Clara whispers.

“What rot.” Quinn sighs. His suit bags at the seams, but a faint glow of health in his cheeks offsets his auburn hair, and he has traded his bandages for an eye patch, which I privately think makes him look rather rakish.

“And you, Miss Lovell?” The photographer folds his black-tipped fingers over his chest and rolls back on his heels. Judging by my imploring letter, Geist must think I’m the most susceptible of us all.

I incline my head politely and say nothing.

The maid reappears in the parlor door. She is a plain thing. Buck-toothed and as jumpy as India rubber. “Dinner’s in the sitting room.”

“Thank you, Viviette,” says Geist. “And now, if you’ll excuse me to my darkroom.” He takes swift leave through the parlor.

“Absurd,” Aunt Clara mutters. “Viviette.” She mistrusts servants who sport exotic names. She thinks it makes them sound wanton.

Eyes averted, the maid leads us to a sitting room cluttered with bric-a-brac. My father once said that the character of a household can be known through the behavior of its staff. I don’t know what to conclude from Viviette’s refusal to meet my gaze.

The sandwiches and cakes are stale, the tea too strong, and the tables and walls are blanketed in photographs of vistas and monuments my eyes are caught by a daguerreotype of Big Ben, the largest clock in London, which I yearn to see. There are also several portraits of Geist himself and stacks of cartes de visite of Geist and of his maid, modeling evening dress, street clothes, and even swathed in Grecian garb. Stealthily, I slip a few into my pocket.

“He watches us, even in his absence.” Quinn rolls his eyes, and we trade a humorous glance.

Silence holds the room until the spiritualist returns. There’s a bounce in his step. “Promising, promising! Now we wait until the varnish has dried and the photograph is printed. Then we shall see the fruits of our labors.”

With no mind to his blackened hands, Geist helps himself to sandwiches and tea before launching into a fascinating recount of his youth in Paris.

“I studied under the esteemed photographer Monsieur Disderi. Odd fellow but brilliant. Disderi made his money in his portraits of the upper classes, such as the present emperor, Napoleon, who considers him to have procured his very best likenesses. But Disderi will also go to great lengths to authenticate rumors of spirit activity. Why, that gentleman once stood sentinel for twenty-four hours at the Place de la Republique in order to photograph Marie Antoinette’s ghost on the scaffold, in her mobcap and with her hands bound.”

“How did he…when did he…?” A crumb trembles on Aunt’s lip.

“There’d been sightings every October sixteenth, the anniversary of her death. Doubters dismissed these as hearsay. Disderi proved them wrong. One glimpse of this image of the last queen of France would turn your hair stone gray. But that is nothing on Disderi’s journey to Scotland and his singular images of pagan spirits who have haunted Tulloch Castle since the twelfth century.”

Geist’s anecdotes are so captivating that eventually even Quinn leans forward in his chair.

“I want to travel the Continent,” he confesses.

“Go first to the City of Light,” says Geist. “Fill your mind with beauty.” He jumps up to leave the room and returns with a stack of tintypes. “Locke ought to have stayed there. He’s destroyed his sanity. But his images will bear witness to this war long after we are departed.” Geist hands them around for us to examine.

I examine portrait images of young boys with guns high as their chests. Rows of the dying. Rows of hospital beds. A look at Quinn, and I can tell that each image has hit him as a punch.

The pictures have a dizzying effect on me, too. I’m not sure if I’m mesmerized or daydreaming, but the heat is with me all at once as my memory catapults me back to last year, a languid August afternoon. Will and I had strayed from our picnic spot to go boating, and a boy, watching us push off from the bank, had decided to rifle through the belongings we had left behind, including Will’s sketchbook. Ripping out the pages…yes, I remember…the little troublemaker had then set them afloat in the water, and Will had blazed with fury. I’d never seen him in such a temper, and it had taken him the rest of the day to calm himself.

My eyes are staring into Will’s eyes black irises ringed in pale blue.

I open my eyes and Will stands before me in blazing life in his Union uniform. The bottoms of his trousers are wet, and water darkly pools the carpet. His anger is palpable. He is so real, so alive, that I can inhale the tang of the salt water that he has carried in with him. If I reached forward, I could ball my fingers in the rough broadcloth of his jacket, my mouth could find that secret space where the carved notch of his collarbone met his throat and

“Miss Lovell!”

Everyone is looking at me.

I blink. Will is gone. I am slumped in my chair, my teacup has fallen, and its liquid has soaked the carpet.

Quinn has left his chair and is bent on one knee before me.

“Jennie?” he whispers softly. “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.” I sit up. “I’m sorry.”

“Miss Lovell, are you unwell?” asks Geist.

“No, no, I’m sorry excuse me, I need air.” Quinn helps me to stand, but his hand, gripping bony at my elbow, is no comfort. I shrug him off, but then I am embarrassed, my palms lifted in protest for anyone to follow. I am careful not to look at Aunt Clara as I hasten out.

Alone in the hall, I untie my collar and fan my cheeks with my fingers. Though my fever ebbs, I have little doubt.

Will was here. He was in this house, in that room, if only for a moment. But it was as true a moment as I have ever lived.

On the front hall table rests a small, paper-wrapped package, twine-tied, inscribed with the name Harding. The package is approximately the same size as the plates Geist had inserted and removed from his camera.

A good spy is never afraid to transgress.

I look over my shoulder. Nobody is in the hall.

My heart could take wing, it’s beating so fast as my fingers unpick the twine. The knot gives too slowly. Then I slide a series of identical photos from their wrapping.

Backed and framed in a cardboard slip, a man sits as grim as a tombstone on the same ornate love seat of Geist’s parlor. Above him hovers a delicate, nearly transparent image. Dressed in gauze, a crown of holly leaves twisted through her pale, streaming hair, the angel appears otherworldly and is more exquisite than my most vivid imaginings.

For a moment I am struck paralyzed. Here is a real angel, caught and captured in all her radiant glory, for anyone to see.

Incredible, but true.

I hold it up to the fanlight for a closer look. There is something familiar in the angel’s profile. I decide to take one of the copies, sliding it into my pocket with the rest of my day’s loot before the family comes to collect me. I compose myself, avoiding Quinn’s eye, my own gaze intent on Aunt Clara’s enormous, bustling skirts.

In the carriage, when I dare to look across at Quinn, he ignores me with a cool indifference that makes me miss his brother all the more. How is it that Will even in spectral vision, if that’s what it was can appear more vital and vibrant to me than anyone else in the family?

I don’t look up again for the rest of the ride home, lest anyone see my suffering, which the Pritchetts would only dismiss as a weakness.

In my attic room the light is weak. I move to the window and spread my secreted photograph on the sill. White winter sky exposes the image. And now I can see the slight protrusion of the angel’s front teeth. I retrieve the other photos from my pocket.

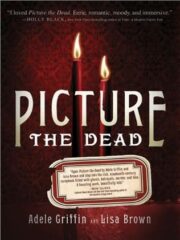

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.