There was only one answer to those questions: these things were so because the cause was hopeless.

James and his Council decided they must retreat in the face of the advancing army; and while this marched north, Mar and James made their arrangements for James to return to France.

So the great rebellion known as the 1715 was quashed almost before it started.

What could the Highlanders do when they heard that their leader had left? There was no point in fighting without a cause.

They returned to the Highlands, there to hide until the '15 was forgotten.

Good luck, not skill, had given the victory to George I.

In London the streets returned to normal; the Jacobites drank their toasts in secret; the camp disappeared from Hyde Park; and the soldiers returned from the north.

Ermengarda settled down happily to discover more opportunities for amassing a fortune; George grunted and was not sure whether he was pleased or sorry. He still thought with deep nostalgia of Hanover. The Prince and Princess of Wales took their walks in the Mall with their band of attendants and friends, talking their German-French-English which never failed to amuse, telling everyone how much they admired England and the English.

They were secure. James would make no more attempts. They felt safer than even before. The attempt had been made and failed; it was as though the people had given their verdict.

But the scribblers were still busy and the rhyme which won the most acclaim at that time and which was repeated in every coffee house, tavern, or wherever men and women congregated, was John Byrom's:

"God bless the King, God bless our Faith's Defender! God bless — no harm in blessing — the Pretender! But who Pretender is and who is King? God bless us all! That's quite another thing,"

The King's Departure

Mary Bellenden was leaning out of the window trying to see the last of a handsome man who had crossed the courtyard and was about to disappear through a door which led to the Prince's apartments.

As he waved and was gone, she sighed and turning sharply was aware of two of the maids of honour who had been watching her.

There could not have been two girls less alike than Margaret Meadows and Sophie Howe. Margaret had now folded her arms and was looking extremely disapproving while Sophie was giggling sympathetically.

"Such unbecoming conduct! " muttered Margaret.

"I see nothing unbecoming," retorted Mary.

"Of course you do not. You are accustomed to such manners that you believe them to be acceptable. It's more than I do."

"Really Margaret," protested Sophie. "Tell me what harm can they do by waving to each other from a window?"

"They've made an assignation no doubt."

"There's nothing wrong in making an assignation," pointed out Sophie. "Of course it depends on what happens when they keep it." She began to laugh so hilariously that, thought Margaret, she could only be remembering her own indiscretions.

"Be silent both of you," commanded Mary, "I won't have you say such things about John."

"So it's John?" cried Sophie.

"Yes, it's John and he is an honourable gentleman and I don't want either of you to start a gossip about him. Do you understand?"

"Oh, we understand, we understand?" cried Sophie. "We understand our Mary is at last in love."

"Don't shout so," reprimanded Margaret. "I never saw such behaviour. And you, Sophie Howe, are the worst of the lot. As for you, Mary Bellenden, you should be careful. These men will talk of love until they get what they want and then ..."

"'Tis true, Mary," agreed Sophie. "Oh, how they talk of love! And afterwards they laugh and tell their friends all about the submissive lady while they advise them to try their luck."

"You don't understand ... either of you. You're too much of a prude, Margaret, and Sophie's too much of a flirt."

"And our dear Mary is ... just as she should be?" laughed Sophie.

"I'm ... serious."

"But is he?" laughed Sophie. "I could tell you a few things. In fact if you want to know anything about the most fascinating subject in the world come to Sophie."

"And what would that be?" demanded Margaret.

"Men!" laughed Sophie.

"If you know anything about them, Sophie Howe, it's all you do know," retorted Margaret.

"There's no need to know anything else, I do assure you, Margaret."

Mary listened to them dreamily. Colonel John Campbell was the handsomest man in the Prince's bedchamber; one day they would marry but for the present they must be content to wait for each other. Poor John had little money; and she, as one of the greatest beauties of the court, was expected to make a brilliant match. In fact everyone knew that the Prince had his eye on her. Not, thought Mary scornfully, that that will do him much good. She was not going to take the easy road to honours by becoming a Prince's—and later perhaps a King's—mistress.

In fact, thought Mary, she would be a fool to take any notice of the Prince's insinuations. He was not really very interested in any woman as a woman; his great desire was to prove his manhood and this he thought he could best do by implying that he was the insatiable lover.

How trivial, how foolish these vanities seemed when compared with the love she and John Campbell had for each other.

One day, John, she was thinking, we'll be married. Perhaps secretly at first ... but shall we care about that? John had told her about the great love of his hero the Duke of Marlborough for his Duchess; they had been married secretly in the days before he had become famous; and whatever might be said of the great Duke or his termagant of a Duchess, none doubted their affection for each other. Their love had endured through all their fame and their misfortunes.

"It shall be so with us," John had said.

He would be as great a soldier as Marlborough, she had replied, but she trusted she would never be such a quarrelsome woman as the Duchess.

She would never be anything but the most charming, the most beautiful woman in the world, he told her.

"You're one who has made up his mind," she had retorted, for the rival charms of herself and Molly Lepel were continuously sung in the court and there were continual arguments as to which of the two was the more beautiful.

"Be careful of the Prince," John had fearfully said; and she had laughingly assured him he had no need to warn her.

Sophie Howe was saying: "I told the man I could not pay him yet. I told him it should be payment enough for him to serve a maid of honour."

"If he complains to the Princess you will be reprimanded I can tell you."

"Oh Margaret, how tiresome good people can be! I tell you I owe such a lot that I dare not try to calculate how much. In fact when a bill is sent to me I hide it ... quickly."

"Which is just what I should expect of you. Don't forget you were one of the chief offenders in church and it's due to you that the maids have to be boarded up. You will be getting a bad reputation, Sophie Howe. I'm surprised that Her Highness keeps you in her service."

"She can hardly dismiss the granddaughter of Grandpapa Prince Rupert ... even though there is a slight blot on the family escutcheon."

"You are a frivolous creature and you'll come to a bad end one day."

"Well I shall have lots of fun on the way there, you can be sure. Oh how I wish I were rich! How I wish I had a nice kind friend who would pay all my bills so that I need not be bothered to hide them."

"That's what we should all like," said Mary, coming out of her day dream. "When I think of all I owe, I shudder."

"Goot day to you, ladies!" The door had been opened and the Prince of Wales, accompanied by the Duke of Argyll, with his brother Lord Islay, and a few of his gentlemen came into the room.

The three girls immediately curtsied and the Prince smiled benignly on them all, but his eyes rested on Mary Bellenden.

"And very pretty you look," he commented.

"Your Royal Highness is gracious," answered Margaret Meadows.

"Always ready to be gracious to pretty young ladies."

His eyes were almost pleading but Mary refused to look at him.

He rocked on his heels and put his hands into his pockets. He brought out some coins which he jingled in his hands.

"Alvays ready to be gracious," he went on; and this time Mary could not avoid his eye. "Very ready," he added.

She bowed her head.

"Your Highness would wish us to acquaint the Princess of your presence?" she asked boldly.

"The Princess, yes. Ve are come to accompany her to the theatre. You like the theatre?"

"Very much. Your Highness."

"It is goot."

Little eyes, alight with desire, implied that, like John Campbell, he thought Mary Bellenden the prettiest girl at Court; and it was fitting, surely, that the Prince should choose the prettiest to be his mistress.

"We must not detain Your Highnesses," said Mary.

And she hurried from the ante chamber to the Princess's apartment.

Caroline enjoyed riding through the streets to Drury Lane. Since the rebellion she had become so popular—more so, she believed, than her husband; and she was secretly pleased that this should be so.

When the Prince became the King she would be Queen and she had no intention of being a background figure, she meant to choose the ministers who would serve them; and she was determined that everyone should realize the importance of the Queen, for, she often wondered, when George Augustus betrayed some foolish vanity, what would become of royalty if she did not take the lead. George Augustus was a fool; he must be to grow angry when he remembered how short he was, and keep a mistress like Henrietta Howard for whom he had no great fancy, merely because he wanted it to be known that he had a mistress. George Augustus was a fool; but his wife was a wise woman.

Therefore it was a pleasure to know that she was becoming known to these people and that they liked what they heard.

She was not only wiser than the Prince but than the King also, for George I cared nothing for his unpopularity which showed he was a fool. He clearly betrayed his preference for Hanover—and that was almost as great an offence in the eyes of the English as his refusal to speak their language. The Prince, though not unpopular like the King, missed opportunities—and the scribblers saw through him and did not hesitate to make their vitriolic pen portraits of him.

Caroline learned that the English enjoyed treating their rulers with derision, and decided she would give them no opportunity to treat her so if she could help it.

"Long live the Princess! Long live the Prince! "

She gazed at him uneasily. Did he notice that the cheers for the Princess were a little more prolonged than those for the Prince? She hoped not, or he would be angry with her. How well she was beginning to know this little husband of hers! That was all to the good. The more she understood, the easier it would be to handle him.

"They like us veil," he murmured; and he bowed graciously, his hand on his heart, to a young woman in the crowd.

"It gives me pleasure," said Caroline, "to see how you they like more than your father."

"Ah, they hate that old devil. And I love them for it."

George Augustus laughed happily and those watching said that the Prince and Princess were on the best possible terms, and they gave an extra cheer for the Princess, reminding each other how good she had been during the winter, which had been a hard one.

There was a special cheer from the boatmen who earned their living by ferrying along the river. They had much to be grateful for to the Princess of Wales who had helped them when they were starving.

They would remember the season just passed as that terrible winter when the Thames had been frozen over, when it had been possible to drive a horse and cart from bank to bank and roast an ox on the ice.

That would in future be known as The Winter of the Great Freeze and the Great Hardship, when it had not been possible to ply a waterman's trade. The Princess had concerned herself with their sufferings, had raised money for them. So there was many a poor waterman who would give a cheer for the good Princess every time her carriage rolled by.

There were others who remembered how she had pleaded for leniency towards those poor devils who had been caught up in the '15 rebellion. Not that her pleading had had much effect on sour old George. He didn't seem to want his English crown but he was pitiless enough with those who had tried to deprive him of it. They had seen the executions of Lord Derwentwater and Lord Kenmure. They had heard how the Countess of Nithsdale had implored the King for leniency towards her husband and of George's brutal rejection of that distracted lady.

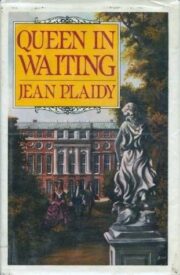

"Queen in waiting" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Queen in waiting". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Queen in waiting" друзьям в соцсетях.