At first I thought the young man in the king’s livery was bent on some similar errand, or that he’d come to collect a fresh supply of garments like the ones he wore. In addition to making the fancy robes and doublets worn by the king and his noblemen, royal tailors also provide livery for the king’s servants. But this individual stopped beneath my window, considered the house for a long moment, and then, as if he sensed me watching him, tilted his head back until our gazes locked.

Bright noonday sun revealed eyes of a deep, dark brown flecked with amber. The rest of his face was equally appealing—strongly defined features and a ready smile.

I recognized him then. When the king had first said the name John Harington, I’d known which of the gentleman choristers he meant, but I’d only seen Master Harington from a distance. His impact had been muted.

When I continued to stare at him, he doffed his feathered cap, revealing a full head of thick brown curls. Then he bowed in my direction.

Behind me, I heard the rustle of fabric. One of my sisters came up to stand beside me, but I did not look away from the young man below to see which one it was. He, however, took note of her, bowed again, and then passed out of sight beneath the overhang.

“What a toothsome young gentleman!” Bridget leaned far out the window, hoping for a glimpse of the back of him as he entered Father’s shop. “And he wears the king’s livery. Who is he?” She was already heading for the stairs.

Mother Anne’s sharp command prevented her from descending. “Your father does not need your help with a customer, Bridget. Return to your mending, if you please.”

Bridget looked mutinous and would surely have argued, had she not heard the sound of heavy footsteps coming our way. Father entered first but Master Harington was right behind him.

My throat went dry. Close at hand, he was even more pleasing to look at. Indeed, he was the most appealing man I had ever seen. Yes, I know I was not yet twelve years old, but he had barely reached his eighteenth year. To the mind of a girl on the verge of womanhood, even the king himself, with all his glittering jewels, could not surpass this young and handsome fellow for masculine beauty.

Bridget was no more immune to Master Harington’s charms than I was. Her avid gaze devoured him. Had Mother Anne not caught hold of her arm, she’d have been across the room to his side in a flash.

Father cleared his throat. “Allow me to make known to you Master John Harington, gentleman of the Chapel Royal. He has been sent by the king to give Audrey music lessons.”

Bridget’s face fell. “Have we not already suffered enough? She is always humming some tune she heard in church or on the street.”

Stung by her derisive tone, I defended myself. “Sometimes I sing the words.”

“For the most part, you do not know the lyrics, if there even are any. You invent your own.”

“An admirable skill,” Master Harington interrupted, turning Bridget’s taunt into a compliment. His eyes twinkled with delight. “With my teaching, Mistress Audrey will become even more proficient at singing and songwriting.”

Father presented Mother Anne to Master Harington. As is the custom when greeting those who are truly welcome, she gave him a friendly kiss, making me think that he, unlike Master Petre the dancing master, must have desirable connections at the royal court.

Elizabeth was next to be introduced, then Bridget. Giggling, they followed Mother Anne’s example. When it was my turn, I went up on my tiptoes to brush my lips against the smooth, soft, sweet-smelling skin of his cheek. The touch was brief but sufficient to send heat flooding into my face.

Master Harington cocked his head and studied me. His interest lingered longest on my hair, which I wore long and loose, as maidens are wont to do. He glanced back at me again as Father presented Muriel to him.

“A fine family,” Master Harington said, accepting Muriel’s shy kiss of greeting. He was already returning to me. “I have been sent to teach you to play the lute, Mistress Audrey, and any other instrument you care to learn. What will it be? The virginals? The harp? I am proficient with everything from the cittern to the sackbut.”

There were too many choices. And he was standing too close to me. I was unable to form an answer.

“The instruction shall be as pleases you, Master Harington,” Father cut in, “but it would please me greatly if you would extend your teaching to all my children.”

Master Harington hesitated. Then his gaze roved to Bridget. She smiled and dimpled . . . and subtly shifted position to better display the rounded fullness of her breasts.

“It shall be as you wish, Master Malte.” Turning to my sisters, he began to question them about what skills they already possessed. He seemed pleased at the prospect of tutoring them, especially Bridget.

I stood a little apart to watch her preen and flirt, and struggled with emotions I had never felt before. For the first time in my life, I understood why my sister reacted so violently when she saw me singled out to receive something she wanted.

10

Stepney, October 1556

Master Eworth cleared his throat. “I have lost the light,” he announced. “I can paint no more today.”

Surprised by how much time had passed since she’d begun her tale, Audrey eased herself to her feet. Hester had already scrambled out of her chair and gone to look at the unfinished portrait on the easel.

“I have no face,” she complained.

Although the artist had lovingly reproduced the embroidery on the child’s dress, her features were as yet little more than a pale blur.

“After the next session you will have eyes and a nose,” Audrey promised, touching a fingertip to the latter appendage and making Hester giggle.

Master Eworth made no promises. He finished packing away his supplies and departed, trailing a whiff of linseed oil in his wake and seeming as glad to be done with them for the day as they were to see him go.

“Was that the truth?” Hester asked when the door had closed behind him. “Did you fall in love with my father the first time you saw him?”

Audrey laughed. “Near enough. He was . . . and is—as my sister said—a most toothsome fellow.”

“And did he return your love?”

Holding her smile while she answered required considerable effort. “You must remember that I was only a little girl when we first met. But he was always considerate of my feelings. And he was an excellent teacher.”

“Father is the most wonderful man in the whole world,” Hester said.

The child idolized him, as she should. Audrey knew exactly how she felt. “Your father has a way with people.”

Jack Harington had charmed everyone in the house on that long-ago day . . . everyone except Edith. Audrey’s new maidservant had been dismissive, calling him “a puffed-up courtier.”

“Will you tell me more on the morrow, when Master Eworth comes to paint me again?”

“Perhaps not then,” Audrey temporized. “Parts of the story I have to tell you are for your ears alone.”

“Then we must find another time, for I want to know everything!”

“The entire tale will take some time in the telling.”

“Then you must continue it as soon as may be.” Hester’s eyes were bright with anticipation. “Tonight? After we sup?”

“I . . . yes. That will do very well.”

Hester’s enthusiasm had the girl capering in a circle before she left the room. Audrey watched her go with mixed emotions. How much, she wondered, should she tell her daughter? She would not lie, but there were incidents that could be omitted from the tale. Indeed, Hester’s tender years argued in favor of an expurgated version of the past.

On the other hand, Hester was an intelligent child. Her lessons had begun when she was still on leading strings. Besides that, from an early age, she observed those around her and learned from what they did. It had been more than a year ago when she’d shocked her mother with an account of watching the milkmaid couple with one of the stable boys in an empty horse stall at Catherine’s Court. She had pronounced the experience “interesting” and had seemed to grasp the power of the attraction between a man and a woman even though she was still far too young to experience it for herself.

Better to tell her all of it, Audrey decided, even the painful parts.

That evening, Audrey joined Hester in the child’s bedchamber and sent the servants away. She tucked her daughter into bed with the pillows plumped behind her head and positioned herself at the foot, her legs folded under her. This was the way tailors often sat, their work in their laps. Audrey kept her fingers busy with a piece of embroidery but her mind was not on her stitches.

“Tell me more about you and Father,” Hester demanded as soon as she was settled. “You promised you would tell me everything!”

Audrey smiled. “Some of it you have heard already. There is no secret about your father’s background.”

“Father came from an impoverished gentry family,” Hester related, happy to show off her knowledge, “but he had a gift for composing songs and writing poetry. The king admired that talent and rewarded him. Is that what giving him the commission to teach you was? A reward?”

“I suppose it was. As a gentleman of the Chapel Royal he had an annuity of thirteen pounds, eight shillings, and nine pence and the king paid him another ten pounds a year to teach me. That does not seem a very great sum to him now that he is a wealthy man, but back then, Jack was grateful for every crumb.”

“Were you good at your lessons?” Hester asked.

“I had a natural aptitude for the lute. I found other instruments more challenging, but none of them defeated me. In time, I mastered the virginals, the recorder, and the viol.”

A wicked gleam came into Hester’s eyes. “How did Aunt Bridget fare?”

Audrey’s sister had never shown much interest in her niece, but they had met on several occasions. These days, Bridget and her husband and their son lived in Somersetshire, although she was not fond of life in the country. Her envy of Audrey was never more apparent than when she visited Catherine’s Court.

“Bridget never learned to carry a tune or play well on any instrument. But, to be fair, she far surpassed me in her ability to perform the intricate steps of the pavane and the galliard. Her accomplishments on the dance floor eased her resentment of me and made her a trifle less likely to give me privy nips.” Those sly pinches had hurt, and sometimes they had left ugly bruises.

“What other tricks did your sister play on you?” Hester asked. “Did she put frogs in your bed?”

“What a notion! No, for she slept there, too.”

Hester’s brow furrowed in concentration. “Did she pretend to trip and spill the contents of a chamber pot all over you?”

“Hester!”

“Well? Did she?”

“No, she did not. Although, if I must be honest, she might have if she could have reasoned out an excuse to be carrying such a thing. We had servants to empty the night soil.” That task had most often fallen to poor, half-witted Lucy.

“Only pinches, then?” Hester tried to hide her yawn, but sleepiness overtook her. She watched her mother through half-closed eyes.

“Pinches and cutting remarks about my appearance, especially the sallow cast of my skin. Bridget’s complexion was as pink and white as that of any great lady at court.”

“Did you go back there?” Hester asked. “To court?”

“I did. And that sparked Bridget’s envy all over again. In time, I learned to ignore both jabs and jibes because I enjoyed every moment of those visits. Your father had a great deal to do with my pleasure.” She smiled, remembering. “I fondly believed that my presence had gone unnoticed by members of the Chapel Royal, but that was not the case. I had simply been ignored, tolerated because I made no attempt to talk to any of them. After Jack was ordered to give me instruction in music, I was formally introduced and invited to listen to their rehearsals. After one such session, the gentleman choristers declared I should be their mascot. I suppose they thought of me the way I thought of Pocket. That is not such a flattering comparison, now that I look back on it, but at the time I was thrilled to be permitted to linger on the fringes while they made their glorious music.”

“Did you see the king again?” Hester murmured in a sleepy voice.

“Not for some time. My lessons began in December. In January, His Grace married Anne of Cleves and he was often . . . distracted. But learning from your father was a delight. He was endlessly patient with me, praising my musical ability while gently correcting and improving my efforts. After the first week, I grew easy in his presence, although an occasional blush did creep up on me when I least expected it.”

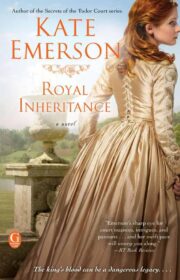

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.