Hester turned toward her mother as a sudden thought struck her. “Was everyone in good health when you returned?” she asked. “Did they escape falling ill of the plague?”

“Everyone was well, although Bridget was much put out that I had spent nearly three months with the royal court while she’d sweltered in the London heat. I tried to tell her that it was just as uncomfortably warm in the country but she did not believe me.”

“That is because it is not true,” Hester said with a giggle.

“I did not want her to feel any more put upon than she already did.”

“Why didn’t your father send the rest of the family to Berkshire? I thought the king granted him property there.”

“Father was granted the rents on property in Berkshire, but the lands and houses themselves already had tenants. Besides, I do not think Mother Anne would have gone, or Bridget, either, for all her complaining. Even more than I was, they were city bred.” She gestured toward a decorative pool that had been dug nearby. “They were accustomed to rats and mice, and flies breed everywhere, but they’d have found the sight of frogs repulsive and I cannot imagine how they would have reacted to being wakened by loud birdsong and a cock crowing to announce the dawn.”

“There are roosters in London.”

“But other sounds, to which city dwellers become accustomed, drown out their raucous early morning greeting.”

Audrey sat a little longer, still enjoying the feel of the sun on her face, but the afternoon was already fading and the air was chillier than it had been. She realized, of a sudden, that she had worn herself out with talking.

“It is time to go in. We will continue this on the morrow.”

“Oh, no! Not yet. First you must tell me where Father was all the time you were with the court.”

“He was in Calais by then, with Sir Thomas Seymour.”

“But he came back to England. He must have. You and Father married and I was born.”

“That was much later.” Audrey sighed. So much of her story remained untold, but she was committed now to finishing it. “I must rest for a little, Hester. Tomorrow will be time enough to continue my tale.”

“During my session with Master Eworth?”

“After, I think.” The portrait painter had heard more than he should have already.

But on the morrow, there was no opportunity for private speech. Jack Harington returned that evening from his latest visit to Hatfield, the Hertfordshire manor house some twenty miles north of London where Princess Elizabeth and her recently reorganized household resided.

“We leave for Catherine’s Court by the end of the week,” he announced.

Hester was ecstatic. She loved their home in Somersetshire and was delighted at the prospect of spending time with her father. Audrey was less sanguine about this sudden change in plans. Jack’s original intention had been to remain in Stepney through the coming winter.

“What have you done?” she demanded of her husband the moment they were alone together in their bedchamber.

“Naught that concerns you, my dear. Have you given orders for the maids to pack your belongings and Hester’s?”

“I have, as you requested, but what are we to tell Master Eworth? Hester’s portrait is not yet complete.”

“Eworth will have to finish it from memory. We cannot delay our departure.”

Worse and worse, Audrey thought. There was something amiss and his refusal to speak of it with her meant that it was deadly serious. Once she’d have thought he was protecting her. Now she suspected he simply did not trust her to obey him if she knew the whole truth.

Crossing the room, she placed one hand on his arm, frowning when she saw how bony her fingers looked against the dark fabric of his doublet. Jack shook her off and refused to meet her eyes.

He had done something foolish, she thought. Something that could imperil them all.

Throwing tact aside—it had rarely proven useful to her in the past—she moved in front of him, forcing him to look at her.

“Haven’t you learned your lesson yet?” she demanded. “You’ve been a prisoner in the Tower twice already for meddling in the succession. If you are suspected of treason a third time, Queen Mary will order your execution without a second thought.”

In these troubled days, when Queen Mary and her Spanish husband could clap a man—or a woman—into gaol for a careless word, it was sheer folly to tempt fate by plotting against them. Every attempt to replace King Henry’s eldest daughter as queen had failed. First, supporters of the Lady Jane Grey had attempted to usurp the throne. Then there had been an ill-conceived rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger. Arrests and executions had resulted from both. Following Wyatt’s disastrous uprising, and as a direct result of it, Jack had found himself in the Tower.

She could not fault her husband’s loyalty to Princess Elizabeth, or to the religious faith in which they’d both been reared, but so long as Mary sat on the throne, either allegiance might have deadly consequences. The fires of Smithfield burned bright to consume so-called heretics. A dank, cold cell in the Tower awaited those judged to be traitors, followed by the most terrible and ignominious death imaginable—to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, the severed parts afterward displayed to strike fear into all who saw them.

A shudder racked Audrey’s thin frame. Only a few months earlier, the so-called Dudley Conspiracy had come to light. Jack had sworn he was not involved with the conspirators and she’d believed him, but he was plotting something now. She was certain of it.

“You cannot help the Lady Elizabeth if you are in prison, or if you are dead.”

“Would you have me run away? Go into exile in France or the German states?”

“Others have, there to wait for the queen to die. Mary has borne no child and likely will not, given her age. In time, Elizabeth will succeed her half sister.”

“How much time? We have already waited three long years.”

“As long as it takes! Think of your daughter, Jack, if not of me! If you are condemned, your estate is forfeit. She will be left destitute.”

“You have kin who will take you in.” His cold voice held no hint of the laughing young man Audrey had once known.

“I’d rather beg in the street than throw myself on Bridget’s mercy.”

“You—”

“There is no one else, Jack. No one. Father, Mother Anne, and Muriel have all gone to their reward. My family consists of you and Hester and I will fight for what is best for our child.”

He drew in a deep breath and ran the fingers of one hand through his thick, dark hair. He’d grown a beard since she first knew him, a luxuriant thing with a mustache above. He tugged on it, as if debating with himself how much to tell her.

“Have I ever betrayed you?” she asked.

He sighed again. “No. But the less you know, the better. All this may come to nothing.”

“They why do we flee London? For that is what you are doing, Jack. Running away.”

“Running to,” he corrected her. “To safety.” The rueful sound he made was not quite a chuckle. “I should think you’d be pleased about that.”

“So you have done nothing yet to incriminate yourself?”

“Naught but listen.”

That meant it was Princess Elizabeth who was planning something dangerous, Audrey thought. “Has she asked you to assist her?”

“No, she has not.”

Audrey thought some more. It was no secret that Queen Mary wanted her half sister to wed the Duke of Savoy. Once married, King Henry’s troublesome younger daughter, Mary’s heir so long as she bore no child of her own, would fall under the control of a husband who was not only Mary’s ally and a good Catholic, but a foreigner. He could take the princess out of England and keep her away.

“I pray every night for a return to the Church of England and an end to Spain’s influence,” she said in a hoarse whisper, “but treason is a fool’s game.”

“Do you not think I’ve learned that? I’ve seen far too many men I admired go to their deaths because they acted against those in power. My one desire is to keep Elizabeth safe from harm. She has only to survive to one day succeed her sister, peacefully and without civil war. There has been enough blood spilt.”

So passionate was this declaration that Audrey found herself unable to argue with it. She slid her arms around her husband’s waist and simply held him for a long moment. Then she pulled away and announced in a brusque and businesslike voice that she would have the household ready to leave Stepney within two days.

Two hectic weeks later, they were settled in at Catherine’s Court. During that time, there had been no opportunity for Audrey to share further confidences with her daughter. She had warned Hester not to speak of what she had already learned. She felt strangely reluctant to have Jack find out what she had begun. She did not think he would approve.

Audrey was still in her bedchamber, breaking her fast with bread and cheese and ale, when Hester burst into the room. “Father has gone off with his steward to tour the estate!” she announced. “He will not be back for hours and hours.”

Her daughter’s excess of energy made Audrey feel tired just looking at her, but what the child wanted was abundantly clear. And she was correct. This was the perfect time to resume her narrative.

22

April 1544

Another war with both France and Scotland seemed imminent in the days just before my sister Bridget married John Scutt. Like Father, he was a royal tailor. A few years earlier, he had been master of the Merchant Taylors’ Company.

He had been courting Bridget for the best part of two years, giving her all the traditional gifts a young lover sends to his future bride. But he was not a young lover. He was nearly fifty to Bridget’s seventeen and had been married twice before. He had a daughter, Margaret, who was eight years old. But he was very wealthy.

Bridget greedily accepted everything he offered—coins, rings, gloves, purses, ribbons, laces, slippers, kerchiefs, hats, shoes, aprons, hose, whistles, crosses, lockets, brooches, gilt knives, silk smocks, a pincase, garters fringed with gold, and even a gown with satin sleeves. As we had all been encouraged to since earliest childhood, she’d stitched linens against the day she’d marry. She had accumulated a goodly supply and Father was prepared to provide anything else that was necessary for her to set up housekeeping.

“But will you be happy with Master Scutt?” Muriel asked her as we dressed her for the ceremony in a new russet wool gown with a kirtle of fine worsted. It was a lovely spring morning. Even London’s air seemed fresher than usual. Our bedchamber was filled with the mingled scents of rosemary, to strengthen memory, and roses, to prevent strife.

Bridget laughed and tossed her long yellow hair, worn loose down her back like a veil on the occasion of her wedding. “He is besotted with me and I mean to keep him so.”

“But he is so old,” her sister persisted.

“If he cannot keep me satisfied,” Bridget confided in a whisper, “I know how to find those who can.”

“Really, Bridget,” Mother Anne chided her, “you should not say such things, not even in jest.”

“Are you certain I am jesting?”

“You had better be. You may not have experienced it yet, but Master Scutt has an evil temper when he feels he has been wronged. You would be wise never to provoke it.”

Bridget only laughed some more. I was the one who worried. Although it rarely deterred any female from marrying, it was common knowledge that after the exchange of vows a husband took control of every facet of his wife’s life. He owned everything that had once belonged to her. She was beholden to him for the clothes on her back and the food on their table. Worse, he could beat her if he chose, and no one would intervene. Once they were one in the eyes of God, he acquired ownership of all her possessions and also of her person. She was as much his chattel as a sheep or a cow.

Muriel and I had spent the last several days before the wedding knotting yards of floral rope. This now hung on every wall of the house. As Bridget’s attendants, we had one more duty. We set to work stitching ribbon favors to her bodice, sleeves, and skirt.

“Baste loosely,” Mother Anne warned us. After the ceremony, these favors would be tugged free by the wedding guests.

When she was ready, Bridget smirked at herself in the looking glass. She did look very fine, even though she wore only two pieces of jewelry. The “brooch of innocence” was prominently displayed on her breast. A gold betrothal ring glinted on one finger. Muriel handed her a garland made of rosemary, myrtle leaves, and gilded wheat ears to carry to the church. That done, we three set out to walk the short distance west along Watling Street from Father’s house to St. Augustine’s church.

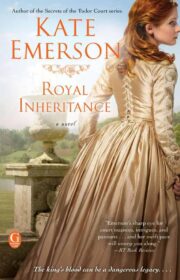

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.