The entire way was strewn with rushes and roses and our neighbors had turned out in force with makeshift instruments, everything from saucepan lids and tin kettles with pebbles inside to drums made of hollow bones. It was an old, old tradition—the noise was supposed to keep evil influences away.

The ceremony was one I’d witnessed many times before. I scarce listened to the droning words but the scene itself affected me strongly. In my mind’s eye, I did not see Master Scutt. Jack Harington stood there, plighting his troth, far more toothsome, and with more teeth left, too. In Bridget’s place, I imagined myself, face radiant, heart slamming against my ribs in anticipation of spending the rest of my life with the man I loved.

“Love, honor, and obey,” I whispered along with my sister, “till death us do part.”

I snapped back to reality when the wedding sermon began. It dealt with the duties of wedlock. The groom was urged to be tolerant, the bride faithful. I wondered if Bridget had any intention of keeping that vow. Most assuredly, she would never stop flirting with any man who appealed to her.

But for the present, the new husband and wife were in harmony. They passed the bride cup around to all the guests. Sops—small pieces of bread—floated in the wine. Before each person drank, he or she dipped a sprig of rosemary into the contents of the cup.

Afterward, everyone returned to Father’s house. A great feast had been prepared, but first Muriel and I had another tradition to uphold, that of breaking a cake over the bride’s head and reading her future in its pieces. It is possible that I enjoyed this act a bit more than I should have, and left a great many more crumbs than necessary ground into Bridget’s long yellow hair, but the chunks that fell to the floor foretold much that was desirable—a son and heir and great wealth. Pleased, Bridget contented herself with finding occasion to pinch me—twice—during the festivities.

It was difficult not to be in a convivial mood. Food and drink were plentiful. Gifts were generous, both from the guests to the newly wed couple and from the bride to those who’d come to see her wed. I did not know all of them. Some were friends of John Scutt and others kin to Bridget’s late mother. I was about to slip away to help Muriel and Mother Anne prepare for the last event of the day when Father beckoned to me.

“This is Audrey, Richard,” he said to the young man standing beside him, a gangly, dark-haired youth who was a stranger to me. I judged him to be a year or two younger than I was. “Audrey, this is Master Richard Darcy. He is about to begin his studies at Cambridge.”

I attempted to make polite conversation by asking him what he would study there. The expression on Darcy’s face put me in mind of a rabbit Pocket had flushed out of the bushes at Ashridge. Did he think I would bite?

He managed to stutter out a reply but it made little sense. I thought he might be rattling off the names of Greek and Latin authors. None was familiar to me.

My effort to talk to him about the wedding was even less successful, but it gave me an excuse to escape. “I must go and help my sister now,” I told him. “It is time for the bedding.”

“Oh, er, yes,” he mumbled, and the rims of his ears turned bright red.

I could not resist. “We’ll put her to bed stark naked,” I said, “and when Master Scutt is brought in, he’ll have been stripped of his clothing, too. They have to consummate their marriage, you know, or it will not be legal.”

He looked everywhere but at me. Then he made a choking sound and fled.

I was smiling as I hastened to the bridal chamber. It was the room where Father and Mother Anne were accustomed to sleep, the best in the house.

Once the bride and groom were tucked under the covers together, Bridget’s blue garters were presented to Master Scutt’s groomsmen and all the pins she’d worn during the day were thrown away. Then Muriel threw one of Bridget’s stockings over her shoulder. She laughed with delight when young John Horner caught it. He’d be next to marry, or so tradition said, and we all knew that his father had been talking to ours about betrothing him to Muriel.

Once Bridget and her new husband drank their posset, we left them alone. I yawned, ready to seek my own bed as soon as all the guests had left the house, but Father waylaid me, drawing me into the window embrasure where we could speak in private. He looked as tired as I felt.

“What did you think of young Darcy?” he asked.

I made a face.

He laughed. “It is early days yet, but consider that he might be a suitable match for you.”

“I do not like him!”

“You have scarce had a chance to get to know him. What is wrong with him?”

He was not Jack Harington, but I could not say that to Father. “I do much dislike his chin,” I said instead. It was the sort that sloped backward toward his neck. I frowned, trying to remember where else I had seen a face with such a feature.

Father sighed. “If you continue to find him distasteful when you get to know him better, I will not force the issue, but will you promise me to give him a fair chance? He’s young yet, and timid in the presence of a pretty girl. He will doubtless improve on further acquaintance.”

At least, I thought, Darcy was not as old as John Scutt. Nor, I supposed, was he as wealthy. “How can a mere stripling like that one provide for me?” I asked.

“It is my duty to make certain that you want for nothing. If you marry, his father will make a settlement of land on the two of you and I will do the same. Indeed, whatever man you wed, you will have a respectable dowry, Audrey, as befits your father’s wealth and position.”

Unspoken was the supposition that any prospective husband, or his family, would match or surpass Father’s contribution to the marriage. That meant that Father would never consider Jack, even though he liked him. Jack had no land of his own and no wealthy father to grant him any. He was no better than a servant in the household of Sir Thomas Seymour, who was himself a younger son.

I knew it was foolish to pine for what could never be. And if I was honest with myself, I had to admit that Jack had never expressed an interest in courting me. We’d been friends. He’d opened up new worlds for me. But more than a year had passed since I’d last seen him. For all I knew, he had forgotten my very existence.

“I know you want only the best for me, Father,” I said, resigned. “I will try to be fair-minded when it comes to Master Darcy.”

23

Soon after Bridget’s wedding, Father purchased leases for lands and manors in Somerset valued at nearly two thousand pounds. He had some idea of spending summers in the country, where there was less danger from the plague. Mother Anne would not hear of it.

“I was born in London and I’ll die in London,” she told him.

“What would we do with ourselves, locked away in some remote manor house?” Muriel wanted to know. Away from her newly acquired betrothed, she meant.

I was wholeheartedly in agreement with them. Only years later did I come to appreciate the joys of country life. That summer, the one during which I celebrated the sixteenth anniversary of my birth, I fed on the energy created by the sheer number of people living inside the old London wall. The wards and parishes throbbed with it.

Even on those days when all we women did was sit by the window, our needles busy on a piece of embroidery or a hem, all manner of things happened just beyond the panes. London is never quiet, never still. Bells toll the hour. Hawkers shout to sell their wares. Riders swear, attempting to make their way through a crush of pedestrians. Carts clatter past, filled with wares from every part of England. All that summer, finely dressed ladies and gentlemen sauntered by Father’s shop, surveying the goods on display.

When we ventured out of the house, I found city life even more stimulating. Blue-coated apprentices mingled with black-clad clergymen, serving maids with staid dowagers. There was bustle and confusion and excitement. We had to be on our guard because pickpockets went everywhere to ply their trade, but that was part of the thrill. A retreat into peace and quiet and safety held little appeal.

In that year, the plague was not the threat people feared most. Invasion by French troops appeared to pose a far greater danger to life and property. We were at war again with our ancient enemy. In mid-July, the king himself left England to lead his troops into battle. His Grace named Queen Kathryn as regent during his absence.

The queen took up residence at Hampton Court, where Prince Edward already had his household, and sent for the two princesses to join them. I was not summoned. I had not expected to be. Nor did Father go to court. With the king gone, there was no employment there for the king’s tailor.

John Scutt, Bridget’s new husband, was royal tailor to the queen. He traveled back and forth by boat throughout the last half of July and all of August. When he was at home in London, he shared the latest court news with his young wife. Sometimes Bridget repeated what he told her. At others she hugged it close to her chest, delighting in knowing something Muriel and I did not.

On one late August evening when the air held the threat of rain, Bridget slipped through the yard and into our house by way of the kitchen. I’d seen Master Scutt return from Hampton Court less than half an hour earlier. Add to that the cat-swallowed-the-linnet expression on Bridget’s face as she burst into the hall and it took no astrologer’s horoscope to predict that she had a secret she was eager to share. I exchanged a speaking glance with Muriel, who knew our sister’s ways as well as I did.

Father and Mother Anne had gone to a supper at the Merchant Taylors’ Hall. So, I presumed, had Master Scutt. The merchant tailors often held meetings and social gatherings there. I do not remember what the occasion was for this one, but in consequence Bridget, Muriel, and I found ourselves alone save for Pocket, and he was sound asleep on a cushion. Edith and the other maidservants remained belowstairs, leaving us to serve ourselves comfits and wine and fresh fruit.

“You will never guess what I just heard.” Bridget’s smirk made me want to strike her.

“That is very true. Perhaps you should simply tell us.” I had been composing a new tune for the lute when she arrived. Now I set that instrument aside and folded my hands in my lap. That seemed the safest place for them if I was to resist the urge to slap my sister’s face.

Bridget wandered with apparent aimlessness from chair to table to window. She ran her hand over every surface, every piece of plate and glass beaker—as if she was trying to evaluate their cost. She had always been acquisitive. Since her marriage she seemed inclined to put a price on everything . . . even information. “What is it worth to you?”

I started to say “nothing” but Muriel spoke first.

“A penny.”

“Not enough.”

“Sixpence, then.” When I looked at her askance, she spread her hands wide to indicate how helpless she was to resist. “Look at her, Audrey. She’s bubbling over like a pot on the boil.”

“And sooner or later she’ll tell all without the necessity of payment. She will not be able to stop herself.”

“Oh.” Crestfallen, Muriel sent Bridget a resentful look. “I suppose you still want the sixpence?”

Bridget held out one hand, palm up, and waited until Muriel paid her. Her fingers curled tight over the silver coin, as if she feared her sister would try to snatch it back. Only after she’d tucked it securely into the purse she wore attached to her belt did she speak.

“The queen means to go on progress next month through Surrey and Kent.”

“There is a royal progress every year,” I said impatiently. “That is not news worth sixpence. I’d value it at less than a farthing.”

“She will take the royal children with her.”

“A penny’s worth. No more.” And not enough to account for Bridget’s barely suppressed glee.

“Master Scutt has seen the itinerary.”

I said nothing to this. A list of stops proposed for the progress did not interest me and I had vowed never to ask why, months after their wedding, Bridget did not yet call her husband by his Christian name. I did not want to be privy to the intimate details of their marriage.

“The queen will stay at Mortlake, Byfleet, Guildford, and Beddington,” Bridget continued, “and at other great houses, too. Her Grace will honor friends at Allington Castle and Merewood with brief visits.”

I pantomimed a yawn. Bridget’s answering scowl pleased me very much.

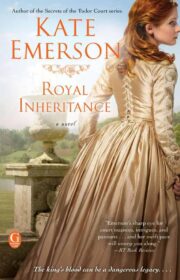

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.