The square of cake I’d just picked up crumbled in my hand. “He is a very bad man.”

She nodded. “And although he claims always to put the Duke of Norfolk’s interests at the forefront, his only true loyalty is to himself. You must never allow yourself to fall under his control, Audrey, else he’ll find a way to use you for his own ends.”

I did not see how he could benefit from an alliance with my family, other than by securing the use of my dowry, but I had every intention of following her advice. “I want nothing to do with him,” I assured her.

We talked of more pleasant matters for a time—fashion and food for the most part. When she asked if I had been to court of late, I admitted that I had not.

“Then come with me on the morrow. I mean to pay a visit to the duchess. She’s had lodgings at Whitehall these last few months, while she’s been attending on Queen Kathryn. She will be happy to see you again.”

I accepted with pleasure.

29

Whitehall, June 10, 1546

We found the Duchess of Richmond in an antechamber in the queen’s apartments, a comfortable little room set aside for quiet pastimes. Several other ladies-in-waiting sat on stools around a low table playing a game of cards. The duchess had been reading. She hastily put her book aside when Mary and I came in, and rose to embrace us warmly, each in turn.

We had scarce begun to exchange news when the Earl of Surrey appeared in the doorway. A ferocious scowl contorted his otherwise pleasant features.

Ignoring everyone else, he stalked toward his sister. Mary and I quickly rose from our places on either side of the duchess and backed away as the earl loomed over her. He did not seem to notice.

“Did you know of this?” His face turned a mottled red as he bellowed the question.

“Know of what, Brother?”

“Father’s grand plan for an alliance with the Earl of Hertford.”

Mary and I exchanged puzzled looks. The Earl of Hertford was Edward Seymour, oldest brother of the late Queen Jane and of Sir Thomas Seymour, Vice Admiral of England. The Duke of Norfolk had not been notably friendly toward any of the Seymours since Jane supplanted Anne Boleyn, Norfolk’s niece, as queen.

Despite her brother’s anger, the duchess remained calm. “Father does not confide in me, Harry. What is he plotting now?” A deep furrow marred the smoothness of her high forehead.

Surrey continued to glare at her. “He means to have you wed Sir Thomas Seymour.”

I gasped. So did two of the ladies playing cards. The duchess’s already fair skin turned whiter still. Beside me, I could feel Mary’s tension as if it were my own.

“There’s more. He proposes that my two sons marry two of Hertford’s daughters.” Vibrating with outrage, his voice rose to a shout. “Who are these Seymours but upstart country gentlemen! Father must be mad to treat with them.”

“They are the brothers of a queen and the uncles of our future king,” the duchess reminded him.

“We have as much royal blood in our veins as Prince Edward!” Surrey raged. “Better you should become the king’s mistress and play the part in England that the Duchess d’Étampes does in France than be married to a Seymour.”

This time the gasps were louder and there were more of them. The earl was oblivious to his audience as he continued to berate his sister. I did not follow most of his rant. I am not certain anyone could have. The shifting allegiances of the court were near impossible to track, even by those close to the center of power. That the duchess had the misfortune to be part of her father’s newest scheme to gain influence at court appeared to be sufficient to bring Surrey’s wrath down on her head. Clearly overwrought, his words were ruled by emotion rather than logic.

“Who is the Duchess d’Étampes?” I whispered to Mary.

“The chief mistress of King Francis of France,” she whispered back.

We retreated farther from the fray but others moved closer, reluctant to miss a word of the earl’s tirade. His ill-considered outburst was the talk of the entire court within an hour. Wagering was heavy that his rash words would have dire consequences the moment they were repeated to the king, but those who thought the earl would be clapped in gaol lost their money. Nothing happened as a result of the incident—no marriages, no alliances, and no arrests.

Or so it appeared at the time.

30

Hampton Court, August 1546

Mary Shelton had been correct about the risk Queen Kathryn had run by preaching to the king. The story was all over London in early August. King Henry had gone so far as to issue an order for the queen’s arrest. Then he had changed his mind. When one of his ministers appeared at court, warrant in hand, King Henry berated him loudly and with as much profanity as he ever allowed himself for daring to suggest that Queen Kathryn was aught but a loving and loyal spouse. To make up for the insult, His Grace showered the queen with gifts. She, having learned her lesson, stopped trying to influence the decisions he made as head of the Church of England.

A few weeks later, on the eve of St. Bartholomew’s Day, a delegation sent by the French king traveled by water to Hampton Court to sign the peace treaty between our two countries. The war was finally over. There were to be ten days of banquets and masques and hunting trips to celebrate.

King Henry sent for his royal tailor. Once again, Father was ordered to bring me along to court.

Tents of cloth of gold and velvet had been set up in the palace gardens at Hampton Court to house some two hundred French gentlemen. Two new banqueting houses had also been erected and were hung with rich tapestries. Awed by all these trappings, I wondered if I would have the courage to carry out the plan I had conceived the moment Father told me that the king wanted to see me.

I meant to demand the truth. His Grace owed me that much, did he not? If the speculation was untrue, then he should be glad to deny it. And if I was his daughter . . . my imagination stopped there. I did not expect anything from him beyond confirmation or denial, but would King Henry believe that? Daily, he was petitioned by hundreds of subjects, all of whom wanted something—lands, money, pardons. I sought knowledge, a far more dangerous thing.

When the king did not send for me, the news that he was to appear at an open-air reception seemed to present me with an opportunity to remind His Grace of my presence. I dressed with great care and left the palace—Father had been assigned both double lodgings and a workroom—to make my way through the grounds.

I stopped some little distance away from the marquee beneath which King Henry stood. His Grace had lost some of his girth since our last meeting. That should have made him appear healthier. Instead he just looked frail.

His clothing was as magnificent as ever, his jewels as plentiful and as sparkling, but he leaned heavily on the shoulder of Archbishop Cranmer, who stood beside him. From time to time, he even allowed the High Admiral of France, the French nobleman who had come to England to sign the peace treaty on behalf of the French king, to support him.

Both the Earl of Hertford and Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Seymour were in close attendance on His Grace. As soon as I recognized the latter, I looked around for Jack Harington. I did not see him at once, but only because of the size of the crowd. I found another familiar face first—that of Sir Richard Southwell.

He had not yet noticed me. Coward that I was, I considered creeping away before he did. Although our encounters had been few and far between, each one had left me with a bad taste in my mouth. I did not relish enduring another conversation with him.

I did not move quickly enough. The young man at his side turned his head my way. With a start, I saw that he was Richard Darcy, the boy Father intended me to marry. Darcy tugged on his father’s sleeve. A moment later, two coldly analytical stares pinned me where I stood.

“This way,” said a familiar voice behind me, and my heart began to race as fast as a cinquepace.

Jack Harington tugged on my arm, drawing me into the concealment of a very large yeoman of the guard. As swiftly as we could, given the crush of people, we fled toward the safety of the palace. I did not look back. If Southwell and his son were following us, I did not want to know it.

“Father’s workroom,” I hissed when we’d slipped through the nearest entrance. “No one will disturb us there.”

“Nor will we be private,” Jack whispered back.

When my steps faltered, he pulled me onward. He said no more but steered me away from the place where Father and two of his apprentices worked and into a deserted passageway. We paused by a window that overlooked the expanse of garden we’d just left. Sir Richard Southwell was still there. He had not pursued me.

Breathing a sigh of relief, I waited for Jack to speak. For the longest time, he did not. He simply stared at me, as if he were trying to memorize my appearance. All the while he looked deeply troubled.

Finally, I grew impatient. “What ails you, Jack?”

“I have begun to think I was wrong.” He reached out to finger a lock of my hair. It had come loose during our precipitous flight. With great care, he tucked it back into place. Everywhere he touched, I felt a line of fire.

“Wrong about what?” I spoke in a breathy whisper. Was he going to declare himself at last?

“About how beautiful you are.”

I frowned. I did not want praise. I wanted love. “I am eighteen years old and not yet betrothed,” I said bluntly.

“You soon will be. They will wear you down.”

I stepped back from him, a spurt of anger burning through my besotted state. “I cannot be forced to wed someone I do not like.”

“You can be coerced. As can I.”

“You are to marry?”

He must have heard the stunned surprise in my voice because a faint smile began to play around his lips. “No, Audrey. I mean that I have been warned to stay away from you.”

“By Sir Richard Southwell?”

“By Sir Thomas Seymour.”

I frowned. “But . . . Sir Richard is Surrey’s man, not Seymour’s.”

“Is he? There are forces at work at court that you know nothing about, Audrey. A struggle for power that will affect us all. You must have a care for yourself. Hold out too long, and there could be terrible consequences for all those you hold dear. For John Malte, mayhap. Or for your sisters.” He gave a short, bitter laugh. “And yes, mayhap for me. No one is safe from the king’s whim, not even the highest peer in the land.”

I blinked at him in confusion. The highest peer in the land was the Duke of Norfolk. Surely Jack did not mean to say that the duke was in danger. “Say what you mean in plain English, Jack.”

“If you anger Sir Richard sufficiently, he will turn vindictive, and he has King Henry’s ear. He has never hesitated to destroy those who stood in the way of something he wanted.”

“Perhaps I, too, have the king’s ear.”

Jack went very still. “Is it true, then?”

I looked away. So, he had wondered if I was a royal merry-begot. “I . . . I do not know. No one will tell me.”

We stood that way, unmoving, staring into each other’s eyes, until the sound of rapidly approaching footsteps broke the spell. A liveried page, scurrying past on some errand, barely spared us a glance, but his appearance was enough to remind us that to be seen together by anyone at this juncture would be most unwise.

“Know this,” Jack said before he left me. “If I were in a position to marry any woman I wished to, it would be you, Audrey.”

Then he was gone.

He hadn’t said he loved me.

Neither had he said that he did not.

Two days later, in Father’s company, I had my long-awaited audience with the king. There was no opportunity to speak with His Grace in private. He called us to him only to inform us that he intended to grant us, jointly, the lordship and manor of Kelston, the lordship and manor of Easton, the capital messuage of Catherine’s Court, and four hundred ewes. The properties were located in Somersetshire. They’d been monastic lands once, forfeited by the nunnery of Shaftesbury when it was dissolved. They were valued at slightly over thirteen hundred pounds.

“It is an exceeding generous gift,” I said to Father after we’d backed out of the presence chamber and returned to our lodgings.

“I am being pensioned off, Audrey,” Father said. “I am to leave my post at court before the end of the year.”

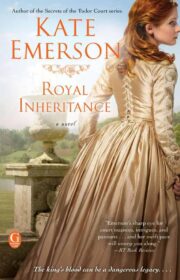

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.