I had walked no farther than the Merchant Taylors’ Hall before another servant came running to fetch me back. Mary Heveningham welcomed me with open arms.

We cried together over the fate of the Earl of Surrey.

After she roundly cursed Sir Richard Southwell for his part in the downfall of the Howards, I admitted that Sir Richard was the reason I had sought her out. My story did not take long to tell. She had guessed most of it already.

“Do you want to claim royal blood as your inheritance?” she asked me in her familiar blunt fashion.

“No!”

“That is wise. But consider that it is also true that your dowry is sufficient to make Sir Richard determined upon the match. And for a certainty, that wretched man does not like to be thwarted.”

“Let him find some other heiress!”

“Young Richard is baseborn, Audrey. That counts against him with some girls’ fathers.”

“But a bastard is good enough for a bastard? Is that it?” I let my bitterness show.

“Still,” Mary said thoughtfully, “there may be some advantage to continued resistance. I have not done so badly refusing to be rushed into marriage.”

“But Tom Clere died,” I objected.

For a moment, her eyes swam with unshed tears. She hastily brushed them away. “He did. And I will grieve all my life for him. But I have a good husband and a fine healthy daughter and am about to return to them. I only came to London to fulfill a promise to the duchess.”

I was suddenly ashamed. I had not even thought to ask after the Duchess of Richmond. “Where is Her Grace?”

“At Reigate in Surrey, not so very far away. She has been granted the care of her brother’s daughters.”

“And their governess?”

“Your Edith’s mother? Yes. She is with them. They’re safe enough, and have sufficient funds to live upon, although all of the duchess’s possessions were confiscated by the Crown at the same time they took everything that belonged to her father and brother. She was fortunate the king allowed her to keep the clothes on her back.”

“Will they execute the duke?”

Mary shook her head. “I wish I knew. That is why I came here—to present a petition to the new Privy Council to spare Norfolk’s life. The Lord Protector granted me a few minutes of his time, but he was not encouraging. I very much fear that, at the least, the duke will remain a prisoner so long as young Edward is king.”

“I pray the king will spare the Duchess of Richmond’s father,” I murmured, acutely aware that it had been my own father, who even now still lay in state in Westminster, who had imprisoned Norfolk and wanted him dead.

“And I will pray that God spare yours.” At my startled look, Mary said, not unkindly, “John Malte, Audrey. Perhaps he is not as ill as you think. Has a physician been called in?”

“He will not have one. He consulted a doctor the last time he was seriously ill and the treatments the fellow prescribed were so distasteful, and so ineffectual, that he lost all faith in medical men.”

“A healer then? Some wise woman skilled in the use of herbs?”

But I shook my head. “He’ll take possets from Mother Anne—his wife—but naught else. And those do little but ease his pain. I fear he is dying, Mary. He grows weaker every day. I . . . I think he has lost the will to live, especially after word reached him of the king’s death.” As Mary had, I swiped at my tears before they could fall. Fishing a handkerchief out of my pocket, I blew my nose.

“I am saddened by your grief, my friend, and you will not like me much for saying this, but it will serve you best if John Malte does not recover.”

At first I did not think I could have heard her correctly, but she repeated this outrageous statement, adding, “You know already that one of the few rights a girl has is to refuse a marriage that is distasteful to her. There is another part of the law you may not have heard. I suspect that men keep silent about it for their own advantage. It is this: a girl who is fourteen or older and not yet betrothed to anyone at the time of her father’s death can inherit in her own right. So long as she remains unmarried, she keeps control of her property and her person. You must not, no matter how great your desire to ease John Malte’s mind, allow him to extract a deathbed promise from you. Stand fast, my friend, and you will soon be free.”

I swallowed hard. This was good news, but it brought with it a terrible sense of guilt. How could I wish for Father to die the sooner? I loved him. I wanted him to live as long as possible. And I was certain that, unlike Mary’s father, John Malte would never force me into accepting a betrothal against my will.

I returned home in an even greater perturbation of mind than when I’d left.

I do not like to remember the days that followed. Father was in pain and I made it worse by refusing to countenance a betrothal. Without Mary’s warning, I might well have thought to ease his suffering with a lie, making a promise I had no intention of keeping. Had I done so, my fate would have been sealed. Such a vow, before witnesses, is binding.

The funeral cortege taking King Henry’s body to Windsor for burial left Westminster on the fourteenth day of February. On the fifteenth, John Malte breathed his last.

We were all at his bedside. Mother Anne and I had been in nearly constant attendance for weeks. At the end we were joined by Mary, Elizabeth, Bridget, and Muriel and their husbands.

“I’ve named you executor,” Father said to John Scutt, although he had to pause for breath between words. “You and Bridget together. Anne will give you my will when the time comes.”

Bridget looked so pleased that I wanted to kick her.

“Take care of Audrey. She has no one else.”

Scutt frowned but promised.

Then Father turned to me. I feared he was about to ask me once again to agree to marry Sir Richard Southwell’s son, but he only smiled a little sadly, closed his eyes, and died.

Mother Anne and I clung together, weeping, for a very long time. By the time I recovered myself enough to pay attention, Bridget had Father’s will in hand and was working herself up into a fine fury over the provisions.

“Listen to this!” she exclaimed. “To Joanna Dingley, otherwise Joanna Dobson, twenty pounds. Five pounds to the foundling child left at my gate. To Audrey Malte my bastard daughter begotten on the body of Joanna Dingley, now wife of one Dobson, the manor of Andesay otherwise Nyland in Somerset.” She stopped reading, her face purpling with rage. The list of manors in my inheritance, I supposed, went on and on and on.

“Father was generous to all of us,” Muriel said in a futile attempt to cool her sister’s temper.

“But he loved her best. It was ever so!”

I knew from long experience that it was no good trying to reason with Bridget. I ignored her outburst and concentrated on comforting Mother Anne as best I could. Of all of us, she would feel Father’s loss most deeply. Adding to her grief was the responsibility of running the tailor’s shop and seeing that Father’s apprentices finished their training. She would have to decide whether to take over, as was her right as a widow, or sell out to another member of the Merchant Taylors’ Company.

The new king’s coronation took place a few days after Father died. The entire city turned out for his procession through London to the Tower. They celebrated with bonfires and fireworks when he was duly crowned. Although King Edward was just a little boy and England would, it seemed, be ruled by his uncle, the Duke of Somerset, most ordinary citizens looked upon the change in the monarchy as a reason for celebration. King Henry had not been as popular in his last years as when he first came to the throne. Many hoped the new regime would be better.

I simply hoped that Sir Richard Southwell had less influence with the new king than with the old one. In this I feared I was to be disappointed. He sent word through John Scutt that he awaited my agreement to the marriage contract he and Father had negotiated.

“I am past the age of fourteen,” I informed Bridget’s husband. “I am of age to inherit on my own and to decide my own fate, as well. Tell Sir Richard that I will not marry his son and that I will never change my mind.”

That son left his studies at Lincoln’s Inn to come to the house and ask to see me. I refused to speak with him.

Master Scutt delayed submitting Father’s will for probate, which meant I had no ready money of my own and no way to claim the lands bequeathed to me. I therefore also lacked the wherewithal to do anything but stay on in Watling Street with Mother Anne.

Although she was still deeply sunk in her own grief, she kept a watchful eye on me. I could tell that something worried her. That suspicion was confirmed when she took me aside and warned me to guard myself well anytime I ventured out of the house.

She looked as if she wished to say more but was unsure whether she dared voice her thoughts.

“What have you heard?” I took both her hands in mine and willed her to meet my eyes.

“Nothing.”

“Then what do you suspect?”

She pulled free of my grip and went to stand by the window. “What do you see from here, Audrey?”

“John Scutt’s house.”

“The day you turned Southwell’s son away, he left here and went directly there.”

I considered that. As executor of Father’s will, Master Scutt had already shown himself willing to delay handing over my inheritance. Such meddling did not alter my rights. I could not be forced into marriage. Indeed, if he continued to withhold my property, I could take him to court.

Confident that, in time, any legal issues would be settled in my favor, I counted my blessings. I had a roof over my head and food in my belly. And even though he was now a very old dog, I had Pocket to cuddle when I needed comfort.

41

February 27, 1547

On the first Sunday in Lent, we went to church as we always did. The congregation included my sisters and their husbands, all of us still wearing mourning for Father, as we would be expected to for some months to come. Mother Anne would wear black for him for the rest of her life.

I avoided Bridget and Master Scutt, but Mother Anne spent some little time talking with them before we returned to the house. Her worried frown warned me she had more bad news to impart.

“Does he still refuse to fulfill his duties as executor?” I asked. “Mayhap it is time to consult a lawyer.”

“It is more than that.” Unaware that she did so, Mother Anne twisted her hands in the fabric of her skirt, clenching and releasing, clenching and releasing.

I took her arm and led her to the window seat with its view of the street below. “Tell me. Together we will deal with it, whatever it is.”

“You are a good girl, Audrey, but it is yourself you must have a care for, not me. Bridget has never made any secret of her resentment of you. I fear she has let envy rule her. And now Sir Richard seems willing to make it worth her while to conspire with him—”

“Conspire? To do what? No one can force me into a marriage I do not want.”

“I do much fear you may be wrong about that. Heiresses have been kidnapped ere now. And priests bribed.” She seized me by the shoulders, her fingers biting into my arms. “There is no denying that men are stronger than women. You could easily be carried away against your will. Imagine yourself in some remote spot, all the doors locked and guarded by Sir Richard’s men. If, then, his son forced himself upon you to consummate the marriage, there could be no possibility of an annulment.”

“But if there is no marriage, no betrothal, that would be rape.”

“You could be beaten into submission. Thrashed until you signed the papers.”

The picture she painted was an ugly one. I wanted to say she was imagining things, but it was all horribly possible. What recourse would I have if I were subjected to such treatment?

Best to avoid any chance of being captured by such villains, but if Bridget was in league with Sir Richard . . .

I slept little that night. With both Father and King Henry gone, I had only myself to rely upon. I’d heard not a word from Jack Harington since the day he’d brought me back from Windsor Castle. I thought he was still with the new Baron Seymour of Sudeley, but I was not even certain of that.

I needed the protection of someone more powerful than I was if I wished to keep my freedom. There was only one person I could think of who might be persuaded to take me in.

In the very early hours of the next morning, I ordered Edith to pack my belongings and hire a cart to take my boxes to Paul’s Wharf. I told the boatman where I wished to go and in short order we were headed westward on the Thames. It was bone-chillingly cold. The waterman said there was ice-meer in the water—cakes of ice that floated up from the bottom of the river, where it was frigid enough to freeze. Stones and gravel came up with it, making travel by water more hazardous than usual.

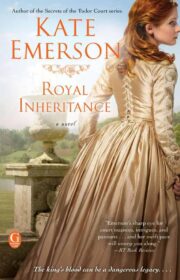

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.