Orders had been given, although I was unaware of them at the time. I was to be clothed and looked after until such time as arrangements could be made for me. The king—for that bejeweled and gentle red-haired man had been no other than King Henry the Eighth himself—had taken exception to my mistreatment by my mother’s husband.

I was taken from my mother and given into the keeping of the king’s tailor, one John Malte by name, and his wife, Anne. Malte was a little man, lean and wiry, with straw-colored hair and sympathetic blue eyes and freckles that danced across the nose and cheeks of a clean-shaven face. His speech was slow and measured—he was wont to choose all his words with care—and even before he knew who I was, he treated me with kindness and consideration. When I fell asleep on a padded bench in his workroom, he covered me with a length of expensive damask.

Many years passed before I learned what transpired while I slept. At the time, I knew only what I was told when I awoke. John Malte took my small hand in his bigger, callused one and informed me that I was to come home with him to London. From that day forward, he said, my name was Audrey Malte.

3

I settled happily into my new life and soon forgot the old. Home was a tall house in Watling Street in London in the parish of St. Augustine by Paul’s Gate. The entire parish stood in the shadow of St. Paul’s.

I shared this house with Mother Anne, Father’s second wife, with her daughter by her first marriage, and with the two daughters Father’s first wife had given him before she died. Elizabeth, at nine, was five years my senior. Bridget was six when I arrived and old enough to resent the addition of yet another sister. Muriel, at age five, welcomed a new playmate.

Time passed.

When I was eight, Father explained my origins to me. He had, he said, begotten me on my mother during one of his many visits to Windsor Castle in the king’s service. I was, he said, a merry-begot, for there had been much joy in my making. I thought this a much nicer word than baseborn or illegitimate or bastard.

In the greater world, the king had married Anne Boleyn, Lady Marquess of Pembroke, and they’d had a daughter, Princess Elizabeth. And then he had divorced and beheaded Queen Anne. When he took another English gentlewoman to wife—Mistress Jane Seymour—she gave birth to a son, a prince who would later ascend the throne as King Edward VI. Then Queen Jane died. That was during the autumn following my ninth birthday.

Father was summoned to court to make mourning garments for the king. Kings wear purple for mourning, but everyone else must dress in black. After Candlemas, the second day of February, courtiers were permitted to resume their normal attire. Father was inundated with orders for new clothes. He worked late into the night and his apprentices with him, squinting in the candlelight to see what they were stitching.

From the beginning, I spent many happy hours in the tailor shop that occupied the large single room on the ground floor of the Watling Street house. A stairway led down to it from the living quarters above, giving me easy access. On occasion, Mother Anne dispatched me with messages for Father. More often, I visited because my sister Bridget persuaded me to go with her. She liked to watch the apprentices work. At eleven, Bridget was already showing signs of budding womanhood. The apprentices liked to watch her, too.

Father customarily set the boys to performing various tasks appropriate to their skill. Since the fabrics he worked with were valuable and not to be cut into lightly, he personally oversaw the laying out of paper patterns traced from buckram pieces onto luxurious fabrics as varied as satin, damask, and cloth of silver.

“Match the grain lines and make certain that the pile runs in the same direction,” he warned. “And the woven designs must be balanced.”

More important still, the pattern pieces had to be arranged so that there was as little waste as possible. Once Father approved the placement of the pattern pieces, he used tailor’s chalk to mark the pattern lines on silk or wool camlet, and even on cloth of gold, but on velvet it was necessary to trace-tack the pattern pieces instead.

Bridget wound a lock of long, pale yellow hair around her finger while she watched two of the apprentices outline each shape with thread. When they were done and Father had checked their stitches, he supervised the removal of the pattern pieces. These were made of stiff brown paper. Father kept them until they wore out, adjusting them to use for more than one person.

In addition to making clothes for the king, Father also had many private clients, women as well as men. They paid him well for his services, allowing us to live in considerable luxury. He had even made a few garments for Queen Anne and for Queen Jane, although it was our neighbor in Watling Street, John Scutt, who held the post of queen’s tailor. Poor Master Scutt lost his wife at about the same time Queen Jane died. Like the queen, she did not survive childbirth. She left her husband with a baby girl he named Margaret.

“I want to help with the cutting,” I announced on this particular day. I was already reaching for Father’s best pair of shears when he stopped me.

“This length of cloth, uncut, must first be sent to the embroiderers. There it will be stretched taut on a frame and they will use our shapes to guide them. See there? All the seam lines are clearly marked. And from the shape, the embroiderers will know whether they are stitching on the front or the back of the garment.”

“And then may I cut it?”

“Then I will cut it. Or Richard will. And afterward, we will make this length of velvet into clothing, with suitable linings and interlinings.”

Richard Egleston was one of Father’s former apprentices. When he finished his training, he married another of Father’s daughters, Mary, the child of his first wife by her first husband, and stayed on in the shop as a cutter.

“I would do a most excellent job for you, Father.” Eager to prove my worth, I persisted in trying to convince him. It had not yet been impressed upon me that girls could not be apprenticed as tailors, or indeed in any other trade.

“You have not had the necessary training to work with such expensive cloth.”

“I can sew,” I argued. “Mother Anne taught me.”

What Father might have said to that, I do not know, for at that precise moment a gentleman entered the shop. I had never seen him before, but I could tell he was a courtier by the way he was dressed. Beneath a fur-lined cloak with the king’s badge on the shoulder he wore the black livery that marked him as a member of the royal household.

He blinked upon first coming inside out of the sunlight. Then his gaze fell upon me. Whatever he had been about to say seemed to fly out of his head. He stood there, silent and staring, until Father spoke to him.

“How may I serve you, Master Denny?” Father’s voice sounded a trifle sharper than usual. “Does His Grace the King require my presence at court?”

Jolted out of his trance, the newcomer recollected his purpose. “He does, Goodman Malte, and His Grace bade me give you this.” Reaching into an inner pocket in his doublet, he withdrew a letter bearing the royal seal.

Bridget and I stayed where we were, our eyes fixed on the stranger. He was younger than Father, but he still seemed quite old to me. He had a very fine brown beard and mild gray eyes.

“Who is he?” I whispered to my sister as Father read the king’s message.

“He must be Anthony Denny, a yeoman of the wardrobe and a groom of the king’s privy chamber.”

That sounded very important, although no more so than “royal tailor.” I was too young yet to grasp the difference between a gentleman born and a merchant whose wealth allowed him to rise into the ranks of the gentry.

When Father finished reading he tossed the missive into the fire burning in the hearth. “We will set out on the morrow,” he promised.

“Is this the lass?” Master Denny jerked his head in my direction.

Bridget, sitting next to me on one of the long workroom tables, assumed he meant her and preened.

“Yes,” Father said. “Audrey, come and make your curtsey to Master Denny.”

I heard Bridget squeak in outrage as I hopped down to obey. She’d come to expect the admiration of males of all ages and was not accustomed to being relegated to second place.

“Tomorrow, Audrey,” Father said, “at King Henry’s request, you will accompany me to court.”

My heart began to beat a little faster. “To court?”

He nodded. “Go along with you now. You and Bridget both. I must speak further of this matter with Master Denny.”

Bridget held her tongue only until we reached the hall on the floor above, the central chamber of our living quarters. Another goodly blaze crackled in that fireplace, sending out waves of welcome warmth and the soothing smell of burning applewood.

“Why were you chosen to visit the king when I am older?”

“How am I to know? Ask Father.”

Bridget pinched my arm hard enough to leave a bruise before turning to the eldest of our sisters. “Elizabeth! Audrey is to go to court with Father! It should have been me!”

Elizabeth glanced up from her embroidery, a puzzled expression on her plump-cheeked face. “Why would either of you want to go to court?” She was nearly fifteen and soon to marry. She cared for little beyond making plans for the household and servants she would have after she wed.

Muriel sat beside Elizabeth on the low settle, all her concentration fixed on the small, even stitches she was using to hem a linen shirt. She had the same yellow hair as Bridget but none of her vivacity. Muriel’s idea of an entertaining afternoon was one spent in the garden feeding bread crumbs to the birds.

“Everyone wants to go to court to see the king!” The exasperation in Bridget’s voice made her opinion clear—if Elizabeth had possessed even a grain of sense, she would never have had to ask.

I said nothing. Although I had not thought of the incident for years, Bridget’s words brought back to me the last occasion upon which I had seen King Henry. At the time, he had frightened me half to death with his booming voice. In hindsight, I realized that he had very likely saved my life.

“It is not fair,” Bridget wailed.

“There is no call to raise your voices,” Mother Anne admonished her, entering the hall from the gallery that crossed over the yard from the countinghouse above the kitchen. “What is all this to-do about?”

Our town house, a tall, sturdy structure made of wood and Flemish wall, was so large and commodious that both a warehouse and a kitchen opened off the cobblestone-paved courtyard at the back of the shop. The family sleeping chambers were above the hall—Elizabeth, Bridget, Muriel, and I shared a room. The apprentices slept in the garret at the very top of the house.

Bridget was only too willing to repeat her complaints for Mother Anne’s benefit.

“Bridget can go in my place,” I offered. “No one will know the difference.”

Mother Anne shook her head. She was a round little dumpling of a woman, good-natured and affectionate, but she could take a firm stand when one was needed. “I very much fear, sweetings, that the king can tell the difference between a redheaded girl and one with yellow curls. You will do as your father tells you, Audrey, and we will none of us mention Bridget’s complaints to him. As for you, Bridget, remember that envy is a sin. Do not allow yourself to fall prey to it.”

4

March 1538

It was still early spring, with a chill in the air. Father bundled me into a warm cloak for the trip upriver to the king’s great palace of Whitehall, in the city of Westminster. We went by boat, embarking from the stairs at Paul’s Wharf.

Father assisted me into the small watercraft he’d waved ashore and indicated that I should sit on one of the embroidered cushions. I watched him closely as he settled in beside me. He did not seem at all nervous about venturing out onto the Thames. I was less sanguine, viewing the choppy water with darkest suspicion. It was a dirty brown in color and there were objects floating in it. I did not want to look too closely at any of them, for I suspected that at least a few were the carcasses of dead animals. I will not even attempt to describe the foul stench that wafted up from beneath the surface.

The waterman extended one grimy hand in our direction while using the other to hold his boat steady. Father gave him a threepenny piece. This seemed extravagant to me. Mother Anne had taught all of her daughters to be frugal with household expenses. Threepence was sufficient to purchase a half-dozen silk points. Two of the small silver coins would have bought a whole pig.

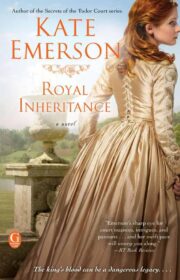

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.