The oars creaked in their locks as the waterman bent to his work and we made good speed upriver on an incoming tide. We did not have far to go, and to make the journey pass even more swiftly, Father pointed out the sights along the way. They were all new to me. Since the day John Malte first took me home with him, I had not once ventured beyond London’s city walls. Even within them, I had rarely gone farther from Watling Street than the shops of Cheapside.

The south bank of the Thames was largely open countryside. We could see across it to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s palace, rising up in distant Lambeth. On the London side, we first passed Blackfriars. Once a great religious house, it had in more recent years been carved up into residences for wealthy pensioners and minor lords.

“Many great noblemen have houses along this stretch of the river,” Father said. “The road that runs from Ludgate to the city of Westminster is called the Strand. We might have ridden along it to our destination, but then we would not have been able to enjoy the best view.”

I agreed that the riverside houses were indeed magnificent. Most had terraces and gardens that ran all the way down to the Thames. Many had their own water gates and landing stairs, too.

The river itself was crowded with every sort of watercraft, from small hired boats like our own to magnificent private barges. Sturdy commercial vessels carried goods downriver for sale in London or export to foreign lands. We made steady progress in spite of the traffic, traveling much faster than if we’d taken the land route. In the Strand, pedestrians, carts, and wagons prevent those on horseback from any better pace than a slow walk.

“Look,” Father instructed as we rounded the bend in the river. I gasped with pleasure as I beheld the gleaming towers of Whitehall, the king’s palace at Westminster. The waterman put his back into his work and guided the boat to the water stairs Father indicated.

A liveried sergeant porter inspected us before we were allowed to pass into the king’s privy garden. He knew Father on sight but he gave me an odd look. I paid him no mind. I was too entranced by my surroundings.

March is not the most beautiful time of year in any garden, but the topiary work and the greenery in the raised beds were very fine. There were gardeners busy everywhere I looked. Some were planting. Others were digging a large, deep hole.

“That will be a pond for the swans,” Father said. “When it is finished it will be bounded by hedges secured to latticework.”

Overlooking the gardens were galleries. Through their large windows I glimpsed courtiers walking back and forth for exercise. I was too far away to make out their faces. It did not occur to me until much later that they could see me as well as I could see them.

We walked along the graveled paths, in no apparent hurry to enter the palace. I wondered at that, and plied Father with questions, but he just shook his head and counseled patience.

The sound of the workmen’s shovels digging into sodden earth seemed loud in the silence that fell between us. In the distance I heard a boatman shout, “Eastward, ho!” And then, without warning, came a strange racket, half bark and half bay. It filled the air, heralding the appearance of a pack of dogs.

They burst out of the shrubbery only a few feet in front of me, tumbling one over another in eager play. I would have been terrified had they been deerhounds, or even terriers, but these dogs belonged to a breed I had never seen before. They were tiny, the largest no more than five inches in height at the shoulder. I counted eight in all.

First one pup, then another, caught sight of me and bounded my way. Then two veered off and began to tussle with each other. The first one bit the second’s ear. Then that pup went for the first dog’s tail. A third, the smallest of the lot, his fur a motley white, red, lemon, and orange-brown, lost interest in me and raced back to join the fun. All three rolled off the graveled path and into the hole the men had been digging.

“Oh, no! They will be hurt!” Alarmed, I ran toward the place where they’d disappeared, trailed by the remaining dogs.

The runt reappeared first, now colored an all-over brown. As I reached him, he gave himself a vigorous shake, spattering my skirt with mud. I could not help myself. I burst out laughing and reached down to lift his warm, filthy, wriggling little body into my arms. Ecstatic at this show of affection, he licked my face.

And so it was, for the second time in my life, that I remained oblivious to the presence of the king, accompanied by a band of his retainers, until His Grace stood not a foot away from me.

King Henry cleared his throat.

I looked up and froze. Dumbstruck, I clutched the small dog closer to my bosom. I had the mad idea that I must protect him from the king.

“Your Majesty,” Father said, bowing low. “May I present my youngest daughter, Audrey Malte.”

I continued to stare at the king, taking in his appearance bit by bit. He was so very splendid to look at that I did not think to curtsey until Father caught my forearm and jerked me downward.

In full sunlight, King Henry the Eighth dazzled the eye. The jewels set into his doublet and his plumed cap reflected the brightness of the day. The rings he wore on every finger glittered, too. And yet, had he been clad in the roughest, undecorated homespun, he’d still have awed onlookers with his magnificence.

Taller by a head than any man in his company, he was broad of shoulder and chest and sturdy of leg. No jewel could outshine the radiance of his nimbus of bright red-gold hair. Its brilliant shade was mirrored in his full beard. Only his eyes lacked gemlike qualities, being a muted blue-gray, but he had an intense and penetrating gaze.

He was also smiling.

“Rise, Audrey,” the king commanded. Then he turned to my father, clapping him on the back as he straightened from his obeisance and causing him to stagger a little. “And good morrow to you, Malte. Well met.”

They began to walk together along the same graveled path Father and I had been following when we encountered the dogs. I looked around for the rest of the pack and spotted them frolicking in one of the newly planted beds. One was digging with wild abandon. The king ignored these antics, apparently unconcerned with the destruction.

Reluctant to be left behind, I joined the king’s entourage, walking behind His Grace and my father. I looked down at the puppy I still held cradled in my arms. Soft brown eyes gazed back at me, full of trust and affection. Belatedly, I noticed that he wore a decorative collar made of red velvet and kid. One of the badges King Henry used—the Tudor rose—was attached to it.

Anthony Denny, the courtier who had brought the king’s message to the tailor shop, fell into step beside me. “That pup you are holding is a called a glove beagle,” he said. “The breed takes its name from the fact that even when full grown, they fit into the palm of a heavy leather hunting glove.”

“Are they lapdogs for ladies, then?” I asked.

“They are most commonly used to hunt rabbits. They ride along on a hunt, usually in a saddlebag, until the larger hounds run the prey to the ground. Then they are released to continue the chase through the underbrush.”

I had never heard of such a thing, but then I knew nothing of hunting, with or without the use of dogs.

Ahead of us, the king continued his conversation with my father, speaking to him in a companionable way that surprised me. No man was the equal of the king. King Henry, as head of the church in England, was only a trifle less to be revered than God Himself. Surely only noblemen were supposed to be on such familiar terms with His Grace.

I considered the evidence before my eyes and came to a conclusion. Father regularly saw His Grace stripped down to his linen—in order that he might fit the king for new clothes. This enforced intimacy must have created a bond between them.

The glove beagles, tired of ravaging through the flower beds, came hurtling after the king. Although he smiled indulgently at the pack, he ordered that they be taken back to their kennel.

“I will take that one now,” one of His Grace’s henchmen said, reaching for the little dog I still held.

“Could I not keep him with me just a little longer?” I asked.

The pup stared up at me with a pleading expression in his dark brown eyes and my heart melted. I darted a glance at the king and quailed when I saw that he was watching me. I feared I had offended him, or broken some rule about how to behave at court, and hastily dropped my gaze.

Heavy footsteps approached, crunching on the gravel, until King Henry stood right in front of me. “Would you like to keep him, Audrey?” he asked.

“More than anything,” I whispered, daring to meet his eyes.

His Grace must have seen the look in mine a thousand times before. Petitioners of all ages and stations in life flocked to court daily to ask for this boon or that. But with me the king was generous.

“Take him as our gift to you, young Audrey,” King Henry said. “Feed him on bread, not meat. That will discourage him from developing hunting instincts. And keep him on a leash or in a fenced yard when you take him out of doors, lest he run off and become lost.”

“I will take most excellent care of him, Your Grace,” I promised, thrilled beyond measure.

Satisfied, the king nodded and straightened. I barely noticed when His Grace left us a few minutes later, along with his escort. I was too busy playing with my new friend.

5

April 1538

I named the glove beagle Pocket, since he was small enough for me to carry in the pocket I wore tied around my waist. Because this pocket was hidden beneath my skirt—reached through a purpose-cut placket—Pocket caused more than one person to start and stare when he poked his head out without warning and announced himself in that strange baying bark that was distinctive to his breed. Mother Anne dubbed it a howl.

Elizabeth and Muriel responded to the little dog much as I had, with instant adoration. He returned their affection. Winning over Mother Anne took longer, nearly a week. Only Bridget refused to be charmed. She was still sulking because I had been chosen to meet the king and she had not.

A month after my visit to Whitehall, I was sleeping soundly when a harsh whisper jerked me awake.

“They are speaking of you,” Bridget hissed into my ear. “Come with me now.”

Still groggy, I allowed myself to be lured from the bedchamber. For once, I left Pocket behind. He was curled into a ball at the foot of the bed, lost in puppy dreams.

Following my sister, I crept quietly down the narrow staircase. Halfway to the lower level, when the rumble of Father’s voice reached me, I tried to pull back, but Bridget was relentless. She caught my arm in a tight grip and all but dragged me the rest of the way.

I knew where she was taking me. From a young age, she had made a habit of concealing herself behind the wall hanging in the hall—an embroidered scene of a picnic in a forest glade—to eavesdrop on Father and Mother Anne.

For one terrifying moment, we were exposed in the doorway and as we scuttled toward this hiding place, our white linen smocks shining like beacons as they caught the candlelight. Then we were safe in the stifling darkness. Neither Father nor Mother Anne had glanced our way.

Father was pacing. I could hear the slap of his slippered feet against the floor as he came close to the wall hanging and then moved away again. After a bit, he spoke.

“The court is a dangerous place for a young girl.”

“Then keep Audrey at home,” Mother Anne replied. The whisper of fabric against fabric told me she held an embroidery frame in her lap. She was calm where Father sounded agitated.

“I have no choice. I must obey the king.”

The news that King Henry wanted me to return to court surprised me. It irritated Bridget. She pinched me. Twice.

Father’s voice faded as he moved away. I missed a few words. And then he was talking about a recent outbreak of violence among the courtiers. “It has been as deadly as any plague,” he complained. “I do not know what spawned it, but there have been brawls, duels, and even murders, all within the verge.”

“The verge?” Mother Anne asked.

“That is the ten-mile radius that surrounds the person of the king. As you know, the king and his courtiers move about a good deal, but wherever King Henry is, that is the court and the verge moves with it.”

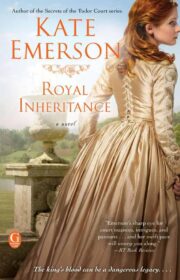

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.