"All right, Grandmère," I said. I sat at the kitchen table while she put up the water. "Grandpère Jack is doing some guiding for hunters again. I just saw him in the swamp with two men. They shot a deer."

"He was one of the best at it," she said. "The rich Creoles were always after him when they came here to hunt, and none ever left empty-handed."

"It was a beautiful deer, Grandmère."

She nodded.

"And the thing is, they won't care about the meat; they just want a trophy."

She stared at me a moment. "What did you tell Paul?" she finally asked.

"That we shouldn't just be with each other, that we should see other people. I told him because I was an artist, I wanted to meet other people, but he didn't believe me. I'm not a good liar, Grandmère," I moaned.

"That's not a bad fault, Ruby."

"Yes, it is, Grandmère," I retorted quickly. "This is a world built on lies, lies and deceptions. The stronger and the more successful are good at it."

Grandmère Catherine shook her head sadly.

"It looks that way to you right now, Ruby honey, but don't give into the comfort of hating everything and everyone around you. Those you call stronger and successful might seem so to you, but they're not really happy, for there is a dark place in their hearts that they cannot deny and it makes their souls ache. In the end they are terrified because they know the darkness is what they will face forever."

"You've seen so much evil and so much sickness, Grandmère. How can you still feel hopeful?" I asked.

She smiled and sighed.

"It's when you stop feeling hopeful that the sickness and the evil wins over you and then what becomes of you? Never lose hope, Ruby. Never stop fighting for hope," she advised. "I know how much you're hurting now and how much poor Paul is suffering, too, but just like this sudden storm, it will end for you and the sun will be out again.

"I always dreamed," she said, coming over to sit beside me and stroke my hair, "that you would have the magical wedding, the one in the Cajun spider legend. Remember? The rich Frenchman imported those spiders from France for his daughter's wedding and released them into the oaks and pines where they wove their canopy of webs. Over them, he sprinkled gold and silver dust and then they had the candlelight wedding procession. The night glittered all around them, promising them a life of love and hope.

"Someday, you will marry a handsome man who could be a prince and you, too, will have a wedding in the stars," Grandmère promised. She kissed me and I threw my arms around her to bury my head in her soft shoulder. I cried and cried and she petted me and soothed me. "Cry honey," she said. "And like the summer rains turn to sunshine so will your tears."

"Oh, Grandmère," I moaned. "I don't know if I can."

"You can," she said. She lifted my chin and looked into my eyes, hers those dark, mesmerizing orbs that had seen evil spirits and visions of the future, "you can and you will," she predicted.

The teapot whistled. Grandmère wiped the tears from my cheeks and kissed me again, and then got up to pour us our cups.

Later that night, I sat by my window and looked up at the clearing sky and I wondered if Grandmère was right; I wondered if I would have a wedding in the stars. The glitter of gold and silver dust danced under my eyelids when I lay my head on the pillow, but just before I fell asleep, I saw Paul's wounded face once more and then I saw the marsh deer open its mouth to voice an unheard scream as it crumbled to the grass.

5

Who is the Little Girl If It's Not Me?

The weeks before summer and the end of the school year took ages and ages to pass. I dreaded every day I attended school, for I knew that some time during the day, I would see Paul or he would see me. During the first few days following our terrible talk, he continued to glare at me furiously whenever he saw me. His once beautiful, soft blue eyes that had gazed upon me with love so many times before were now granite cold and full of scorn and contempt. The second time we approached each other in the corridor, I tried to speak to him.

"Paul," I said, "I'd like to talk to you, to just—"

He behaved as if he didn't hear me or he didn't see me and walked past me. I wanted him to know that I wasn't seeing another boy on the side. I felt dreadful and spent most of my school day with a heart that felt more like a lump of lead in my chest.

Time wasn't healing my wounds and the longer we went on not talking to each other, the harder and colder Paul seemed to become. I wished that I could simply rush up to him one day and gush the truth so he would understand why I said the things I had said to him at my house, but every time I decided I would do just that, Grandmère Catherine's heavy words returned: "Do you want to be the one who puts enmity in his heart and drives him to despise his own father?" She was right. In the end he would hate me more, I concluded. And so I kept my lips sealed and the truth buried beneath an ocean of secret tears.

Many times I had found myself furious with Grandmère Catherine or Grandpère Jack for not revealing the secrets in their hearts and keeping my family history a deep mystery, a mystery it should no longer have been for me at my age. Now, I was no better than they had been, keeping the truth from Paul, but there was nothing I could do about it. Worst of all, I had to stand by and watch him fall in love with someone else.

I always knew that Suzzette Daisy, a girl in my class, had a crush on Paul. She didn't wait long to pursue him, but ironically, when Paul first began spending more and more time with Suzzette Daisy, I felt a sense of relief. He would direct more of his energies toward caring for her and less toward hating me, I thought. From across the room, I watched him sit with her and eat his lunch and soon saw them holding hands when they walked through the school corridors. Of course, a part of me was jealous, a part of me raged over the injustice and cried when I saw them laughing and giggling together. Then I heard he had given her his class ring which she wore proudly on a gold chain, and I spent a night drenching my pillow in salty tears.

Most of the girls who had once been envious of Paul's affection for me now gloated. Marianne Bruster actually turned to me in the girls' room one June afternoon and blared, "I guess you don't think you're someone special anymore since you were dumped for Suzzette Daisy."

The other girls smiled and waited for me to respond.

"I never thought I was someone special, Marianne," I said. "But thank you for thinking so," I added.

For a moment she was dumbfounded. Her mouth opened and closed. I started past her, but she spun about, flinging her hair over her face, then tossing it back and whipping around to make it fan out in a circle as she grinned broadly at me.

"Well, that's just like you," she said, her hands on her hips, her head wagging from side to side as she spoke. "Just like you to be smart about it. I don't know where you come off being snotty," she continued, now building on her anger and frustration. "You're certainly no better than the rest of us."

"I never said I was, Marianne."

"If anything, you're worse. You're a bastard child. That's what you are," she accused. The others nodded. Encouraged, she reached out to seize my arm and continue. "Paul Tate finally has shown some sense. He belongs with someone like Suzzette and certainly not a low-class Cajun like a Landry," she concluded.

I pulled away and brushed at my tears as I rushed from the girls' room. It was true—everyone thought Paul belonged with someone like Suzzette Daisy and thought they were the perfect couple. She was a pretty girl with long, light brown hair and stately features, but more important, her father was a rich oil man. I was sure Paul's parents were overjoyed at his choice of a new girlfriend. He'd have no trouble getting the car and going to dances with Suzzette.

Yet despite his apparent happiness with his new girlfriend, I couldn't help but detect a wistful look in his eyes when he saw me occasionally and especially at church. Starting a relationship with Suzzette, and the passage of more time since our split-up, finally began to calm him. I even thought he was close to speaking to me, but every time he seemed to be headed in that direction, something stopped him and turned him away again.

Finally, mercifully, the school year ended, and with it my daily contact with Paul, as slight as it had been. Outside of school he and I truly did live in two different worlds. He no longer had any reason to come my way. Of course, I still saw him at church on Sunday, but in the company of his parents and sisters, he especially wouldn't even look in my direction. Occasionally, I would hear what sounded like his motor scooter's engine and go running to my doorway to look out in anticipation and in the hope that I would see him pull into our drive just as he used to so many times before. But the sound either turned out to be someone else on a motorcycle or some old car passing by.

These were my days of darkness, days when I was so sad and tired that I had to fight to get out of bed each morning. Making everything seem worse and harder was the intensity with which the heat and the humidity greeted the bayou this particular summer. Everyday temperatures hovered near a hundred with humidity often only a degree or two less. Day after day the swamps were calm, still, not even the tiniest wisp of a breeze weaving its way up from the Gulf to give us any relief.

The heat took a great toll on Grandmère Catherine. More than ever, she was oppressed by the layers and layers of heavy humidity. I hated it when she had to walk somewhere to treat someone for a bad spider bite or a terrible headache. More often than not, she would return exhausted, drained, her dress drenched, her hair sticking to her forehead and her cheeks beet red; but these trips and the work she did resulted in some small income or some gifts of food for us and with the tourist trade dwindling down to practically nothing during the summer months, there wasn't much else.

Grandpère Jack wasn't any help. He stopped even his infrequent assistance. I heard he was hunting alligators with some men from New Orleans who wanted to sell the skins to make pocketbooks and wallets and whatever else city folk made out of the swamp creatures' hides. I didn't see him much, but whenever I did, he was usually floating by in his canoe or drifting in his dingy and guzzling some homemade cider or whiskey, satisfied to turn whatever money he had made from his gator hunting into another bottle or jug.

Late one afternoon, Grandmère Catherine returned from a treateur mission more exhausted than ever. She could barely speak. I had to rush out to help her up the stairs. She practically collapsed in her bed.

"Grandmère, your legs are trembling," I cried when helped her take off her moccasins. Her feet were blistered and swollen, especially her ankles.

"I'll be all right," she chanted. "I'll be all right. Just get me a cold cloth for my forehead, Ruby, honey."

I hurried to do so.

"I'll just lay here a while until my heart slows down," she told me, and forced a smile.

"Oh, Grandmère, you can't make these long trips anymore. It's too hot and you're too old to do it."

She shook her head.

"I must do it," she said. "It's why the good Lord put me here."

I waited until she fell asleep and then I left the house and poled our pirogue out to Grandpère's shack. All of the sadness and days of melancholy I had endured the past month and a half turned into anger and fury directed at Grandpère. He knew how hard it was for us during the summer months. Instead of drinking up his spare money every week, he should think about us and come around more often, I decided. I also decided not to discuss it with Grandmère Catherine, for she wouldn't want to admit I was right and she wouldn't want to ask him for a penny.

The swamp was different in the summer. Besides the waking of the hibernating alligators who had been sleeping with tails fattened with stores, there were dozens and dozens of snakes, clumps of them entwined together or slicing through the water like green and brown threads. Of course, there were clouds of mosquitos and other bugs, choruses of fat bullfrogs with gaping eyes and jiggling throats croaking and families of nutrias and muskrats scurrying about frantically, stopping only to eye me with suspicion. The insects and animals continually changed the swamp, their homes making it bulge in places it hadn't before, their webs linking plants and tree limbs. It made it all seem alive, like the swamp was one big animal itself, forming and reforming with each change of season.

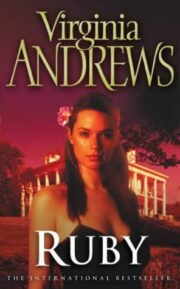

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.