"Oh, it's wonderful, Grandmère. I'm just . . . worried about him."

"Well, worry about him on a full stomach," she ordered. I forced myself to eat, and, despite my disappointment, even enjoyed Grandmère Catherine's custard pie. I helped her clean up and then I went back outside and sat on the galerie, waiting and watching and wondering what had happened to ruin what would have been a wonderful evening. Almost an hour later, I heard Paul's motor scooter and saw him coming down the road as fast as he could. He pulled up and dropped his scooter roughly to run up to the house.

"What happened to you?" I cried, standing.

"Oh, Ruby, I'm sorry. My parents . . . they forbade me to come. My father ordered me to my room when I refused to have dinner with them. Finally, I decided to climb out the window and come here anyway. I must apologize to your grandmother.‖

I sank to the steps of the galerie.

"Why wouldn't they let you come?" I asked. "Because of my grandfather and what happened in town last night?"

"That . . . as well as other things. But I don't care how angry they get at me," he said, stepping up to sit beside me. "They're just being stupid snobs."

I nodded. "Grandmère said this would happen. She knew."

"I'm not going to let them keep me away from you, Ruby. They have no right. They—"

"They're your parents, Paul. You've got to do what they tell you to do. You should go home," I said dryly. My heart felt like it had turned into a glob of swamp mud. It was as if cruel Fate had dropped a sheet of dark gloom over the bayou, and just like Grandmère Catherine often said, Fate was a grim reaper, never kind, with little respect for who was loved and needed.

Paul shook his head. Years seemed to melt from him, and he sat there vulnerable, helpless as a child of six or seven, no more comprehending than I.

"I'm not going to give you up, Ruby. I'm not," he insisted. "They can take away everything they've given me, and I still won't listen to them."

"They'll only hate me more, Paul," I concluded.

"It doesn't matter. What matters is that we care for each other. Please, Ruby," he said, taking my hand. "Say that I'm right."

"I want to, Paul." I looked down. "But I'm afraid."

"Don't be," he told me, reaching out to tilt my head toward him. "I won't let anything happen to you."

I stared at him with huge, wistful eyes. How could I explain? I wasn't worried about myself, I was concerned for him because as Grandmère Catherine always told me, defiance of fate just meant disaster for those you loved. Defying it was as futile as trying to hold back the tide.

"All right?" Paul pursued. "Okay?"

"Oh, Paul."

"It's settled then. Now," he said, standing. "I'm going in to apologize to your grandmother."

I waited for him on the steps. He returned a few minutes later.

"Looks like I missed a real feast. It makes me so angry," he said, gazing out at the road with eyes as furious as Grandpère Jack's could get. I didn't feel comfortable with him hating his parents. At least he had parents, a home, a family. He should hold on to those things and not risk them for the likes of me, I thought. "My parents are unreasonable," he declared firmly.

"They're just trying to do what they think is best for you, Paul," I said.

"You're what's best for me, Ruby," he replied quickly. "They're just going to have to understand that." His blue eyes gleamed with determination. "Well, I'd better go back," he said. "Once again, I'm sorry I ruined your dinner, Ruby."

"It's over now, Paul." I stood up and we gazed at each other for a long moment. What did the Tates fear would happen if Paul loved me? Did they really believe my Landry blood would corrupt him? Or was it merely that they wanted him to know only girls from rich families?

He took my hand into his.

"I swear," he said, "I'll never let them do anything to hurt you again."

"Don't fight with your parents, Paul. Please," I begged.

"I'm not fighting with them; they're fighting with me," he replied. "Good night," he said, and leaned forward to kiss me quickly on the lips. Then he went to his motor scooter and drove into the night. I watched him disappear in the darkness. When I turned around, I saw Grandmère Cather-ne standing in the doorway.

"He's a nice young man," she said, "but you can't rip a Cajun man away from his mother and father. It will tear his heart in two. Don't put all your heart in this, Ruby. Some things are just not meant to be," she added, and turned around to go back into the house.

I stood there, the tears streaming down my face. For the first time, I understood why Grandpère Jack liked living in the swamp away from people.

Despite what had happened on Sunday, I still had high hopes for the Saturday night fais dodo. But whenever I brought it up with Grandmère, she simply replied, "We'll see." On Friday night, I pressed her harder.

"Paul's got to know if he can come by to pick me up, Grandmère. It's not fair to keep him dangling like bait on a fish line," I said. It was something Grandpère Jack would say, but I was frustrated and anxious enough to risk it.

"I just don't want you to suffer another disappointment, Ruby," she told me. "His parents aren't going to let him take you and they would just be furious if he defied them and did so anyway. They would be angry with me, too."

"Why, Grandmère? How can they blame you?"

"They just would," she said. "Everybody would. I'll take you myself," she said nodding. "Mrs. Bourdeaux is going and she and I can sit together and watch the young people. Besides, it's been a while since I heard good Cajun music."

"Oh, Grandmère," I moaned. "Girls my age are going with boys; some have been on dates for more than a year already. It's not fair; I'm fifteen. I'm not a baby anymore."

"I didn't say you were, Ruby, but—"

"But you're treating me like one," I cried, and ran up to my room to throw myself on my bed.

Maybe I was worse off living with a grandmother who was a spiritual treater, who saw evil spirits and danger in every dark shadow, who was always chanting and lighting candles and putting totems on people's doorways. Maybe the Tates just thought we were a crazy family and that was why they wanted Paul to stay away from me.

Why did my mother have to die so young and why did my real father have to desert me? I had a grandfather who lived like an animal in the middle of the swamp and a grandmother who thought I was a small child. My sadness was mixed suddenly with rage. Here I was, fifteen with other girls my age far less pretty than I enjoying themselves on real dates while I was expected to go trailing along with my Grandmère to the fais dodo. Never before did I feel like running away as much as I did now.

I heard Grandmère coming up the stairs, her steps heavier than usual. She tapped gently on my door and looked in. I didn't turn around.

"Ruby," she began. "I'm only trying to protect you."

"I don't want you to protect me," I snapped. "I can protect myself. I'm not a baby," I insisted.

"You don't have to be a baby to need protection," she replied in a tired voice. "Strong grown men often cry for their mothers."

"I don't have a mother!" I shot back, and regretted it as soon as the words left my mouth.

Grandmère's eyes saddened and her shoulders slumped. Suddenly, she looked very old to me. She put her hand on her heart and took a deep breath, nodding.

"I know, child. That's why I try so hard to do what's right for you. I know I can't be your mother, too, but I can do some of what a mother would do. It's not enough; it's never enough, but—"

"I didn't mean to say you don't do enough for me, Grandmère. I'm sorry, but I want to go to the dance with Paul very much. I want to be treated like a young woman and not a child anymore. Didn't you want that when you were my age?" I asked. She stared at me a long moment before sighing.

"All right," she said. "If the Tate boy can take you, you can go with him, but you must promise me you will be home right after the dance."

"I will, Grandmère. I will. Thank you."

She shook her head.

"When you're young," she began, "you don't want to face up to what has to be. Your youth gives you the strength to defy, but defiance doesn't always lead to victory, Ruby. More often than not, it leads to defeat. When you come face-to-face with Fate, don't charge headlong into him. He welcomes that; it feeds him and he's got an insatiable appetite for stubborn, foolish souls."

"I don't understand, Grandmère," I said.

"You will," she told me with that heavy, prophetic tone of hers. "You will." Then she straightened up and sighed again. "I guess I'd better iron your dress," she said.

I wiped the tears from my cheeks and smiled.

"Thank you, Grandmère, but I can do it."

"No, that's all right. I want to keep myself busy," she said, then walked out, her head still hanging lower than usual.

All day Saturday, I debated about my hair. Should I wear it brushed down, tied with a ribbon in the back, or should I wear it up in a French knot? In the end I asked Grandmère to help me put my hair up.

"You have such a pretty face," Grandmère Catherine said. "You should wear your hair back more often. You're going to have a lot of nice boyfriends," she added, more to soothe herself than to please me, I thought. "So remember not to give away your heart too quickly." She took my hand into both of hers and fixed her eyes on me, eyes that looked sad and tired. "Promise?"

"Yes, Grandmère. Grandmère," I said, "are you feeling all right? You've looked very tired all day."

"Just that old ache in the back and my quickened heartbeat now and again. Nothing out of the ordinary," she said.

"I wish you didn't have to work so hard, Grandmère. Grandpère Jack should do more for us instead of drinking up his money or gambling it away," I declared.

"He can't do anything for himself, much less for us. Besides, I don't want anything from him. His money's tainted," she said firmly.

"Why is his money any more tainted than any other trapper's in the bayou, Grandmère?"

"His is," she insisted. "Let's not talk about it. If anything sets my heart beating like a parade drum, that does."

I swallowed my questions, afraid of making her sicker and more tired. Instead, I put on my dress and polished my shoes. Tonight, because the weather was unstable with intermittent showers and stronger winds, Paul was going to use one of his family's cars. He told me his father had said it was all right, but I had the feeling he hadn't told them everything. I was just too frightened to ask and risk not going to the dance. When I heard him drive up, I rushed to the door. Grandmère Catherine followed and stood right behind me.

"He's here," I cried.

"You tell him to drive slowly and be sure you're home right after the dancing," Grandmère said.

Paul rushed up to the galerie. The rain had started again, so he held an umbrella open for me.

"Wow, Ruby, you look very pretty tonight," he said, then saw Grandmère Catherine step out from behind me. "Evening, Mrs. Landry."

"You get her home nice and early," she ordered.

"Yes, ma'am."

"And drive very carefully."

"I will."

"Please, Grandmère," I moaned. She bit down on her lip to keep herself silent and I leaned forward to kiss her cheek.

"Have a good time," she muttered. I ran out to slip under Paul's umbrella and we hurried to the car. When I looked back, Grandmère Catherine was still standing in the doorway looking out at us, only she looked so much smaller and older to me. It was as if my growing up meant she was to grow older, faster. In the midst of my excitement, an excitement that made the rainy night seem like a star-studded one, a small cloud of sadness touched my thrilled heart and made it shudder for a second. but the moment Paul started driving away, I smothered the trepidation and saw only happiness and fun ahead.

The fais dodo hall was on the other side of town. All furniture, except for the benches for the older people, was moved out of the large room. In a smaller, adjoining room, large pots of gumbo were placed on tables. We didn't have a stage as such, but platforms were used to provide a place for the musicians, who played the accordion, the fiddle, the triangle, and guitars. There was a singer, too.

People came from all over the bayou, many families bringing their young children as well. The little ones were put in another adjoining room to sleep. In fact, fais dodo was Cajun baby talk for go-to-sleep, meaning put all the small kids to bed so the older folks could dance. Some of the men played a card game called bourré while their wives and older children danced what we called the Two-step.

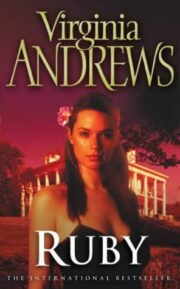

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.