She did her best thinking then, with the salt wind in her face. Mostly she planned. She had a lot to do. She had to find a buyer for her store. And there was the house on Peachtree Street. Rhett paid for the upkeep, but it was ridiculous to have it sitting there empty when she’d never use it again . . .

So she’d sell the Peachtree Street house and the store. And the saloon. That was sort of too bad. The saloon produced excellent income and was no trouble at all. But she’d made up her mind to cut herself free of Atlanta, and that included the saloon.

What about the houses she was building? She didn’t know anything at all about that project. She had to check and make sure the builder was still using Ashley’s lumber . . .

She had to make sure Ashley was all right. And Beau. She’d promised Melanie.

Then, when she was done with Atlanta, she would go to Tara. That must be last. Because once Wade and Ella learned they were going home with her, they’d be anxious to get going. It wouldn’t be fair to keep them dangling. And saying goodbye to Tara would be the hardest thing she had to do. Best to do it quickly; it wouldn’t hurt so much then. Oh, how she longed to see it.

The long slow miles up the Savannah River from the sea to the city seemed to go on forever. The ship had to be towed by a steampowered tugboat through the channel. Scarlett walked restlessly from one side of the deck to the other with Cat in her arms, trying to enjoy the baby’s excited reaction to the marsh birds’ sudden eruption into flight. They were so close now, why couldn’t they get there? She wanted to see America, hear American voices.

At last. There was the city. And the docks. “Oh, and listen, Cat, listen to the singing. Those are black folks’ songs, this is the South, feel the sun? It will last for days and days. Oh, my darling, my Cat, Momma’s home.”

Maureen’s kitchen was just as it had been, nothing had changed. The family was the same. The affection. The swarms of O’Hara children. Patricia’s baby was a boy, almost a year old, and Katie was pregnant. Cat was embraced at once into the daily rhythms of the three-house home. She regarded the other children with curiosity, pulled their hair, submitted to hers being pulled, became one of them.

Scarlett was jealous. She won’t miss me at all, and I cannot bear to leave her, but I have to. Too many people in Atlanta know Rhett and might tell him about her. I’d kill him before I’d let him take her from me. I can’t take her with me. I have no choice. The sooner I go, the sooner I’ll be back. And I’ll bring her own brother and sister as a gift for her.

She sent telegrams to Uncle Henry Hamilton at his office, and to Pansy at the house on Peachtree Street, and took the train for Atlanta on the twelfth of May. She was both excited and nervous. She’d been gone so long—anything might have happened. She wouldn’t fret about it now, she’d find out soon enough. In the meantime she’d simply enjoy the hot Georgia sun and the pleasure of being all dressed up. She’d had to wear mourning on the ship, but now she was radiant in emerald green Irish linen.

But Scarlett had forgotten how dirty American trains were. The spittoons at each end of the car were soon surrounded by evil-smelling tobacco juice. The aisle became a filthy debris trap before twenty miles were done. A drunk lurched unevenly past her seat and she suddenly realized that she should not be travelling alone. Why, anybody at all could move my little hand valise and sit next to me! We do things an awful lot better in Ireland. First Class means what it says. Nobody intrudes on you in your own little compartment. She opened the Savannah newspaper as a shield. Her pretty linen suit was already rumpled and dusty.

The hubbub at the Atlanta Depot and the shouting daredevil drivers in the maelstrom at Five Points made Scarlett’s heart race with excitement, and she forgot the grime of the train. How alive it all was, and vital, and always changing. There were buildings she’d never seen before, new names above old storefronts, noise and hurry and push.

She looked eagerly out the window of her carriage at the houses on Peachtree Street, identifying the owners to herself, noting the signs of better times for them. The Merriwethers had a new roof, the Meades a new color paint. Things weren’t nearly as shabby as they’d been when she left a year and a half back.

And there was her house! Oh. I don’t remember it being so crowded on the lot like that. There’s hardly any yard at all. Was it always so close to the street? For pity’s sake, I’m just being silly. What difference does it make? I’ve already decided to sell it anyhow.

This was no time to sell, said Uncle Henry Hamilton. The depression was no better, business was bad everywhere. The hardest hit market of all was real estate, and the hardest hit real estate was the big places like hers. People were moving down, not up.

The little houses, now, like the ones she’d been building on the edge of town, they were selling as fast as people could put them up. She was making a fortune there. Why did she want to sell anyhow? It wasn’t as if the house cost her anything, Rhett paid all the bills with money left over, too.

He’s looking at me like I smelled bad or something, Scarlett thought. He blames me for the divorce. For a moment she felt like protesting, telling her side of the story, telling what had really happened. Uncle Henry was the only one left who was on my side. Without him there won’t be a soul in Atlanta who doesn’t look down on me.

And it doesn’t matter a bit. The idea burst in her mind like a Roman candle. Henry Hamilton’s wrong in judging me just like everybody else in Atlanta was wrong in judging me. I’m not like them, and I don’t want to be. I’m different, I’m me. I’m The O’Hara.

“If you don’t want to bother with selling my property, I won’t take it against you, Henry,” she said. “Just tell me so.” There was a simple dignity in her manner.

“I’m an old man, Scarlett. It would probably be better for you to hook up with a younger lawyer.”

Scarlett rose from her chair, held out her hand, smiled with real fondness for him. It was only after she was gone that he could put words to the difference in her. “Scarlett’s grown up. She didn’t call me ‘Uncle Henry.’ ”

“Is Mrs. Butler at home?”

Scarlett recognized Ashley’s voice immediately. She hurried from the sitting room into the hall; a quick gesture of her hand dismissed the maid who’d answered the door. “Ashley, dear, I’m so happy to see you.” She held out both her hands to him.

He clasped them tightly in his, looking down at her. “Scarlett, you’ve never looked lovelier. Foreign climates agree with you. Tell me where you’ve been, what you’ve been doing. Uncle Henry said you’d gone to Savannah, then he lost touch. We all wondered.”

I’ll just bet you all wondered, especially your adder-tongued old sister, she thought. “Come in and sit down,” she said, “I’m dying to hear all the news.”

The maid was hovering to one side. Scarlett said quietly as she passed her, “Bring us a pot of coffee and some cakes.”

She led the way into the sitting room, took one corner of a settee, patted the seat beside her. “Sit here beside me, Ashley, do. I want to look at you.” Thank the Lord, he’s lost that hangdog look he had. Henry Hamilton must have been right when he said that Ashley was doing fine. Scarlett studied him through lowered lashes while she busied herself clearing room on a table for the coffee tray. Ashley Wilkes was still a handsome man. His thin aristocratic features had become more distinguished with age. But he looked older than his years. He can’t be more than forty, Scarlett thought, and his hair’s more silver than gold. He must spend a lot more time in the lumberyard than he used to, he’s got a nice color to his skin, not that office gray look he had before. She looked up with a smile. It was good to see him. Especially looking so fit. Her obligation to Melanie didn’t seem so burdensome now.

“How’s Aunt Pitty? And India? And Beau? He must be practically a grown man!”

Pitty and India were just the same, said Ashley with a quirk of his lips. Pitty got the vapors at every passing shadow and India was very busy with committee work to improve the moral tone of Atlanta. They spoiled him abominably, two spinsters trying to see which one was the best mother hen. They tried to spoil Beau, too, but he’d have none of it. Ashley’s gray eyes lit up with pride. Beau was a real little man. He’d be twelve soon, but you’d take him for almost fifteen. He was president of a sort of club the neighborhood boys had formed. They’d built a tree house in Pitty’s backyard, made from the best lumber the mill turned out, too. Beau had seen to that; he already knew more about the lumber business than his father, said Ashley with a mixture of ruefulness and admiration. And, he added with intensified pride, the boy might have the makings of a scholar. He’d already won a school prize for Latin composition, and he was reading books far above his age level—

“But you must be bored by all this, Scarlett. Proud fathers can be very tedious.”

“Not a bit, Ashley,” Scarlett lied. Books, books, books, that was exactly what was wrong with the Wilkeses. They did all their living out of books, not life. But maybe the boy would be all right. If he knew lumber already, there was hope for him. Now, if Ashley would just not get all stiff-necked, she had one more promise to Melly that she could settle. Scarlett put her hand on Ashley’s sleeve. “I’ve got a big favor to beg,” she said. Her eyes were wide with entreaty.

“Anything, Scarlett, you should know that.” Ashley covered her hand with his.

“I’d like for you to promise that you’ll let me send Beau to University and then with Wade on a Grand Tour. It would mean a lot to me—after all, I think about him as practically my son, too, seeing that I was there when he was born. And I’ve come into really a lot of money lately, so that’s no problem. You can’t be so mean that you’d say no.”

“Scarlett—” Ashley’s smile was gone. He looked very serious.

Oh, bother, he’s going to be difficult. Thank goodness, here’s that slowpoke girl with the coffee. He can’t talk in front of her and I’ll have a chance to jump in again before he has a chance to say no.

“How many spoons of sugar, Ashley? I’ll fix your cup.”

Ashley took the cup from her hand, put it on the table. “Let the coffee wait for a minute, Scarlett.” He took her hand in his. “Look at me, dear.” His eyes were softly luminous. Scarlett’s thoughts were distracted. Why, he looks almost like the old Ashley, Ashley Wilkes of Twelve Oaks.

“I know how you came into that money, Scarlett. Uncle Henry let it slip. I understand how you must feel. But there’s no need. He was never worthy of you, you’re well rid of Rhett, never mind how. You can put it all behind you, as if it never happened.”

Great balls of fire, Ashley’s going to propose!

“You’re free from Rhett. Say you’ll marry me, Scarlett, and I’ll pledge my life to making you happy the way that you deserve to be.”

There was a time when I would have traded my soul for those words, Scarlett thought, it’s not fair that now I hear them and don’t feel anything at all. Oh, why did Ashley have to do that? Before the question was formed in her mind, she knew the answer. It was because of the old gossip, so long ago it seemed to be now. Ashley was determined to redeem her in the eyes of Atlanta society. If that wasn’t just like him! He’ll do the gentlemanly thing even if it means tearing up his whole life.

And mine, too, by the way. He didn’t bother to think of that, I don’t suppose. Scarlett bit her tongue to keep from unleashing her anger on him. Poor Ashley. It wasn’t his fault he was the way he was. Rhett said it: Ashley belonged to that time before the War. He’s got no place in the world today. I can’t be angry or mean. I don’t want to lose anyone who was part of the glory days. All that’s left of that world is the memories and the people who share them.

“Dearest Ashley,” Scarlett said, “I don’t want to marry you. That’s the all of it. I’m not going to play belle games with you and tell lies and keep you panting after me. I’m too old for that, and I care for you too much. You’ve been a big piece of my life all along, and you always will be. Say you’ll let me keep that.”

“Of course, my dear. I’m honored you feel that way. I won’t distress you by referring again to marriage.” He smiled, and he looked so young, so much like the Ashley of Twelve Oaks that Scarlett’s heart turned over. Dearest Ashley. He mustn’t ever guess that she’d clearly heard relief in his voice. Everything was all right. No, better than all right. Now they could truly be friends. The past was neatly finished.

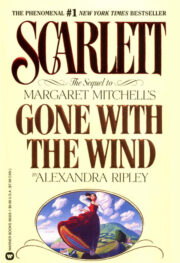

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.