“Cat doesn’t like town. Can we ride to the river?”

“All right. I haven’t been to the river in a long time, that’s a good idea.”

“May I climb up in the tower?”

“You may not. The door’s too high, and it’s more than likely full of bats.”

“Will we go see Grainne?”

Scarlett’s hands tightened on her reins. “How do you know Grainne?” The wise woman had told her to keep Cat away, to guard her close to home. Who had taken Cat there? And why?

“She gave Cat some milk.”

Scarlett didn’t care for the sound of it. Cat only referred to herself in the third person when something made her nervous or angry. “What didn’t you like about Grainne, Cat?”

“She thinks Cat is another little girl named Dara. Cat told her, but she didn’t hear.”

“Oh, honey, she knows it’s you. That’s a very special name she gave you when you were just a little baby. It’s Gaelic, like the names you gave Ree and Ocras. Dara means oak tree, the best and strongest tree of all.”

“That’s silly. A girl can’t be a tree. She doesn’t have leaves.”

Scarlett sighed. She was overjoyed when Cat wanted to talk, the child was so often quiet, but it wasn’t always easy to talk to her. She’s such an opinionated little thing, and she always can tell when you’re fudging a little. The truth, the whole truth, or she gives you a look that could kill.

“Look, Cat, there’s the tower. Did I tell you the story how old it is?”

“Yes.”

Scarlett wanted to laugh. It would be wrong to tell a child to lie, but sometimes a polite fib would be welcome.

“I like the tower,” said Cat.

“I do too, sweetheart.” Scarlett wondered why she hadn’t come here for so long. She’d almost forgotten how strange the old stones made her feel. It was eerie and peaceful at the same time. She made a promise to herself not to let so many months slip away before her next visit. This was, after all, the real heart of Ballyhara, where it had begun.

The blackthorn was already blooming in the hedges and it was still April. What a season they were having! Scarlett slowed the buggy for a long sniff. There was no real need to hurry, the dresses would wait. She was driving into Trim for a package of summer clothes Mrs. Sims had sent. There were six invitations to June house parties on her desk. She wasn’t sure she was ready to start partying so soon, but she was ready to see some grown-ups. Cat was her heart of hearts, but . . . And Mrs. Fitz was so busy running the big household that she never had time for a friendly cup of tea. Colum had gone to Galway to meet Stephen. She didn’t know how she felt about Stephen coming to Ballyhara. Spooky Stephen. Maybe he wouldn’t be so spooky in Ireland. Maybe he’d just been so strange and silent in Savannah because he was mixed up in the gun business. At least that was over! The extra income she was getting now from the little houses in Atlanta was pleasant, too. She must have given the Fenians a fortune. Much better spent on frocks; frocks didn’t hurt anyone.

Stephen would have all the news from Savannah, too. She was longing to know how everyone was. Maureen was just as bad about writing letters as she was. She hadn’t heard anything about the Savannah O’Haras in months. Or about anyone else. It made sense that when she’d made the decision to sell up in Atlanta she’d decided to put everything in America behind her and never look back.

Still, it would be nice to hear about Atlanta folks. She knew, from the profits she was making, that the little houses were selling, so Ashley’s business must be good. What about Aunt Pittypat, though? And India? Had she dried up so much she was dust? And all those people who had once been so important to her so long ago? I wish I’d kept in touch with the aunts myself instead of leaving money with my lawyer to send them their allowance from. I was right not letting them know where I was, I was right to protect Cat from Rhett. But maybe he wouldn’t do anything now; look at the way he was at the Castle. If I write to Eulalie, I’ll get all the Charleston news from her. I’ll hear about Rhett. Could I bear it to hear that he and Anne are blissfully happy, raising racehorses and Butler babies? I don’t believe I want to know. I’ll let the aunts stay like they are.

All I’d get anyhow is a million crossed pages of lecturing, and I get enough lecturing from Mrs. Fitz to fill that hole. Maybe she’s right about giving some parties; it is a shame to have that house and all those servants standing idle. But she’s dead wrong about Cat. I don’t give a fig what Anglo mothers do, I’m not going to have a nanny running Cat’s life. I see little enough of her now, the way she’s always off at the stables or in the kitchen or wandering over the place or up a tree somewhere. And the idea of sending her away to some convent school is just plain crazy! When she’s old enough, the school in Ballyhara will do just fine. She’ll have friends there, too. It’s worrisome to me sometimes that she never wants to play with any other children… What on earth is going on? It’s not Market Day. Why’s the bridge all jammed up with people like this?

Scarlett leaned down from the buggy and touched a hurrying woman on the shoulder. “What’s happening?” The woman looked up. Her eyes were bright, her whole face excited.

“It’s a flogging. Better hurry, or you’ll miss it.”

A flogging. Scarlett didn’t want to see some poor devil of a soldier being whipped. She had an idea that flogging was punishment in the military. She tried to turn the buggy around, but the pushing, hurrying mass of people avid to see the spectacle caught her up in their press. Her horse was buffeted, her buggy rocked and pushed. The only thing she could do was get down and hold the bridle; soothe the horse with strokes and soft sounds, walking at the pace of the people around her.

When forward motion stopped, Scarlett could hear the whistling of the lash and the dreadful liquid sound it made when it landed. She wanted to cover her ears, but she needed her hands to gentle the frightened horse. It seemed to her that the ghastly noises went on forever.

“. . . one hundred. That’s it,” she heard, then the groaning disappointment of the mob. She held tightly on to the bridle; the pushing and shoving was worse than before as the crowd dispersed.

She didn’t shut her eyes until too late. She’d already seen the mutilated body, and the picture was burned on her brain. He was tied onto an upright spoked wheel, his wrists and ankles bound with leather thongs. A purple-stained blue shirt hung over his rough woolen pants from the waist, baring what must have once been a broad back. Now it was a giant red wound with loose red strips of flesh and skin hanging from it.

Scarlett turned her head into the horse’s mane. She felt sick. Her horse tossed his head nervously, throwing her away. There was a terrible sweet smell in the air.

She heard someone vomiting, and her stomach heaved. She leaned over as best she could without releasing the bridle and was sick onto the cobbles.

“All right then, lad, there’s no shame to losing your breakfast after a flogging. Go along to the pub and have a large whiskey. Marbury’ll help me cut him down.” Scarlett raised her head to look at the speaker, a British soldier in the uniform of a sergeant in the Guards. He was talking to an ashen-faced private. The private stumbled away. Another came forward to assist the sergeant. They cut the leather from behind the wheel, and the body fell into the bloodsoaked mud beneath it.

That was green grass last week, Scarlett thought. This can’t be. That’s meant to be soft green grass.

“What about the wife, Sergeant?” A pair of soldiers were holding the arms of a silent, straining woman in a hooded black cloak.

“Let her go. It’s over. Let’s go. The cart will come later to take him away.”

The woman ran after the men. She caught the sergeant’s goldstriped sleeve. “Your officer promised I could bury him,” she cried. “He gave me his word.”

The sergeant shoved her away. “I only had orders for the flogging, the rest is none of my business. Leave me be, woman.”

The black-cloaked figure stood alone on the street, watching the soldiers walk into the bar. She made one sound, a shuddering sob. Then she turned and ran to the wheel, the blood-covered body. “Danny, oh Danny, oh my dear.” She crouched, then kneeled in the ghastly mud, trying to lift torn shoulders and lolling head into her lap. Her hood fell away, revealing a pale fine-boned face, neatly chignoned golden hair, blue eyes in shadowed circles of grief. Scarlett was frozen in place. To move, to clatter wheels over cobbles would be an obscene intrusion on the woman’s tragedy.

A dirty little boy ran barefoot across the square. “Can I have a button or something, lady? My ma wants a keepsake.” He shook the woman’s shoulder.

Scarlett raced over the cobbles, the blood-spattered grass, the edge of the churned mud. She grabbed the boy’s arm. He looked up, startled, mouth gaping. Scarlett slapped his face with all the strength in her arm. The sound of it was like the crack of a rifle shot. “Get out of here, you filthy little devil! Get out of here.” The boy ran, bawling with fear.

“Thank you,” said the wife of the man who had been beaten to death.

She was in it now, Scarlett knew. She had to do what little could be done. “I know a doctor in Trim,” she said. “I’ll go get him.”

“A doctor? Will he want to bleed him, do you think?” Her bitter, desperate words were English-accented, like the voices at the Castle balls.

“He’ll prepare your husband for burial,” said Scarlett quietly.

The woman’s bloody hand seized the hem of Scarlett’s skirt. She lifted it to her lips, an abject kiss of gratitude. Scarlett’s eyes clouded with tears. My God, I don’t deserve this. I would have turned the buggy if I could. “Don’t,” she said, “please don’t.”

The woman’s name was Harriet Stewart, her husband’s Daniel Kelly. That was all Scarlett knew until Daniel Kelly was in the closed coffin inside the Catholic Chapel. Then the widow, who had spoken only to answer the priest’s questions, looked around her with wild, darting eyes. “Billy, where’s Billy? He should be here.” The priest found out that there was a son, locked in a room at the hotel to keep him away from the flogging. “They were very kind,” said the woman, “they let me pay with my wedding ring, though it’s not gold.”

“I’ll bring him,” Scarlett said. “Father? You’ll take care of Mrs. Kelly?”

“That I will. Bring a bottle of brandy, too, Mrs. O’Hara. The poor lady’s near breaking.”

“I will not break down,” Harriet Kelly said. “I cannot. I must take care of my boy. He’s such a little boy, only eight.” Her voice was thin and brittle as new ice.

Scarlett hurried. Billy Kelly was a sturdy blond boy, big for his age, loud with anger. At his captivity behind the thick locked door. At the British soldiers. “I’ll get a rod of iron from a smithy and smash their heads till they shoot me,” he shouted. The innkeeper needed all his burly strength to hold the boy.

“Don’t be a fool, Billy Kelly!” Scarlett’s sharp words were like cold water thrown in the child’s face. “Your mother needs you, and you want to add to her grief. What kind of man are you?”

The innkeeper could release him then. The boy was still. “Where is my mother?” he said, and he sounded as young and frightened as he was.

“Come with me,” said Scarlett.

80

Harriet Stewart Kelly’s story was revealed slowly. She and her son had been at Ballyhara for more than a week before Scarlett learned even the bare bones of it. Daughter of an English clergyman, Harriet had taken a post as assistant governess in the family of Lord Witley. She was well educated, for a woman, nineteen, and completely ignorant of the world.

One of her duties was to accompany the children of the house on their rides before breakfast. She fell in love with the white smile and playful lilting voice of the groom who also accompanied them. When he asked her to run away with him, she thought it the most romantic adventure in the world.

The adventure ended on the small farm of Daniel Kelly’s father. There were no references and so no jobs for a runaway groom or governess. Danny worked the stony fields with his father and brothers, Harriet did what his mother told her to do, for the most part scrubbing and darning. She had mastered fine embroidery as one of the accomplishments necessary to a lady. That Billy was her only child was testimony to the death of the romance. Danny Kelly missed the world of fine horses in grand stables and the dashing striped waistcoat, top hat, and tall leather boots that were a groom’s dress livery. He blamed Harriet for his fall from grace, consoled himself with whiskey. His family hated her because she was English, and Protestant.

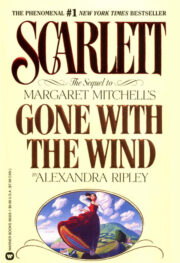

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.