“Grainne will be expecting us, Momma. We made a lot of noise.”

“All right, honey, I’m coming.”

The wise woman looked no older, no different from the first time Scarlett had seen her. I’d even be willing to bet those are the same shawls she was wearing, Scarlett thought. Cat busied herself in the small dark cottage, getting cups from their shelf, raking the ancient-smelling burning peat into a mound of glowing embers for the kettle. She was very much at home. “I’ll fill the kettle at the spring,” she said as she carried it outside. Grainne watched her lovingly.

“Dara visits me often,” said the wise woman. “It’s her kindness to a lonely soul. I haven’t the heart to send her away, for she sees the right of it. Lonely knows lonely.”

Scarlett bristled. “She likes to be alone, she doesn’t have to be lonely. I’ve asked her time and again if she’d like to have children come play, and she always says no.”

“It’s a wise child. They try to stone her, but Dara is too quick for them.”

Scarlett couldn’t believe she’d heard right. “They do what?” The children from the town, Grainne said placidly, hunted through the woods for Dara, like a beast. She heard them, though, long before they got to her. Only the biggest ever came near enough to throw the stones they carried. And those came near only because they could run faster than Dara on longer, older legs. She knew how to escape even them. They wouldn’t dare chase her into her tower, they were afraid of it, haunted as it was by the ghost of the young hanged lord.

Scarlett was aghast. Her precious Cat tormented by the children of Ballyhara! She’d whip every single one of them with her own hands, she’d evict their parents and break every stick of their furniture into splinters! She started up out of her chair.

“You will burden the child with the ruin of Ballyhara?” said Grainne. “Sit you down, woman. Others would be the same. They fear anyone different to themselves. What they fear they try to drive away.”

Scarlett sank back onto the chair. She knew the wise woman was right. She’d paid the price for being different herself, again and again. Her stones had been coldness, criticism, ostracism. But she had brought it on herself. Cat was only a little girl. She was innocent. And she was in danger! “I can’t just do nothing!” Scarlett cried. “It’s intolerable. I’ve got to make them stop.”

“Ach, there’s no stopping ignorance. Dara has found her own way, and it is enough for her. The stones do not wound her soul. She is safe in her tower room.”

“It’s not enough. Suppose a stone hit her? Suppose she got hurt? Why didn’t she tell me she was lonely? I can’t bear that she’s unhappy.”

“Listen to an old woman, The O’Hara. Listen from your heart. There is a land that men know of only from the songs of the seachain. Its name is Tir na nOg, and it lies beneath the hills. Men there are, and women too, who have found the way to that land and have never been seen again. There is no death in Tir na nOg, and no decay. There is no sorrow and no pain, nor hatred, nor hunger. All live in peace with one another, and there is plenty without labor.

“This is what you would give your child, you would say. But listen well. In Tir na nog, because there is no sorrow, there is no joy.

“Do you hear the meaning of the seachain’s song?”

Scarlett shook her head.

Grainne sighed. “Then I cannot ease your heart. Dara has more wisdom. Leave her be.” As if the old woman had called her, Cat came through the door. She was concentrating on the heavy, waterfilled kettle, and she didn’t look at her mother and Grainne. The two of them watched silently while Cat methodically set the kettle on the iron hook over the coals, then raked more coals into a heap below it.

Scarlett had to turn her head. If she continued to look at her child, she knew she wouldn’t be able to stop herself from grabbing Cat in her arms and holding her tightly in a protective embrace. Cat would hate that. I mustn’t cry, either, Scarlett told herself. It might frighten her. She’d sense how frightened I am.

“Watch me, Momma,” said Cat. She was carefully pouring steaming water into an old brown china teapot. A sweet smell rose from the steam, and Cat smiled. “I put in all the right leaves, Grainne,” she chortled. She looked proud and happy.

Scarlett caught hold of the wise woman’s shawl. “Tell me what to do,” she begged.

“You must do what’s given you to do. God will guard Dara.”

I don’t understand anything she says, thought Scarlett. But somehow her terror was relieved. She drank Cat’s brew in the companionable silence and warmth of the herb-scented shadowy room, glad that Cat had this place to come to. And the tower. Before she returned to Dublin, Scarlett gave orders for a new, stronger rope ladder.

88

Scarlett went to Punchestown for the races this year. She’d been invited to Bishopscourt, the seat of the Earl of Clonmel, who was known as Earlie. To her delight, Sir John Morland was also a guest. To her dismay, the Earl of Fenton was there.

Scarlett rushed over to Morland as soon as she could. “Bart! How are you? You’re the biggest stay-at-home I’ve ever heard of in my life. I look for you all the time, but you’re never anywhere.”

Morland was gleaming with happiness and cracking his knuckles loudly. “I’ve been busy, the most splendid kind of busy, Scarlett. I’ve got a winner, I’m sure of it, after all these years.”

He’d talked like this before. Bart so loved his horses that he was always “sure” each foal was the next Grand National champion. Scarlett felt like hugging him. She’d have loved John Morland even if he had no connection at all to Rhett.

“. . . named her Diana, fleet of foot and all that sort of thing, you know, plus John for me. Hang it all, I’m practically her father except for the biology part. It came out Dijon when I put it together. Mustard, I thought, that won’t do at all. Too damn French for an Irish horse. But then I thought again. Hot and peppery, so strong it makes your eyes water. That’s not a bad profile. Sort of ‘get out of my way, I’m coming through’ and all that. So Dijon it is. She’s going to make my fortune. Better lay a fiver on her, Scarlett, she’s a sure thing.”

“I’ll make it ten pounds, Bart.” Scarlett was trying to think of some way to mention Rhett. What John Morland was saying didn’t register at first.

“. . . be really sunk if I’m wrong. My tenants are doing that rent strike thing the Land League dreamed up. Leaves me without money for oats. I wonder now how I could have thought so highly of Charles Parnell. Never thought the fellow would end up hand in glove with those barbarian Fenians.”

Scarlett was horrified. She’d never dreamed the Land League would be used against anyone like Bart.

“I can’t believe it, Bart. What are you going to do?”

“If she wins here, even places, then I suppose the next big one is Galway and after that Phoenix Park, but maybe I’ll sort of tuck in one or two smaller races in May and June, to keep her mind on what’s expected of her, so to speak.”

“No, no, Bart, not about Dijon. What are you going to do about the rent strike?”

Morland’s face lost some of its glow. “I don’t know,” he said. “All I’ve got are my rents. I’ve never evicted, never even thought of it. But now I’m up against it, I might have to. Be a bloody shame.”

Scarlett was thinking about Ballyhara. At least she was safe from any trouble. She’d forgiven all rents until the harvest was in.

“I say, Scarlett, I forgot to mention it. I received some good news from our American friend Rhett Butler.”

Scarlett’s heart leapt. “Is he coming over?”

“No. I was expecting him. Wrote to him about Dijon, you see. But he wrote back that he couldn’t come. He’s to be a father in June. They took extra care this time, kept the wife in bed for months until there wasn’t any danger of what happened last time. But everything’s splendid now. She’s up and happy as a lark, he says. He is too, of course. Never saw a man in my life cared as much about being a proud father as Rhett.”

Scarlett caught hold of a chair for support. Whatever unrealistic daydreams and hidden hopes she might have had were over.

Earlie had reserved a complete section of the white iron grillework stands for his party. Scarlett stood with the others, scanning the course through mother-of-pearl opera glasses. The turf track was brilliant green, the infield of the long oval was a mass of movement and color. People stood on wagons, on the seats and roofs of their carriages, walked around singly and in groups, massed at the interior rail.

It began to rain and Scarlett was grateful for the second her of grandstand overhead. It made a roof for the privileged seat-holders below.

“Good show,” Bart Morland chortled. “Dijon is a great little mudder.”

“Do you fancy anything, Scarlett?” said a smooth voice in her ear. It was Fenton.

“I haven’t decided yet, Luke.”

When the riders came onto the track, Scarlett cheered and applauded with the rest. She agreed twenty times with John Morland that even the naked eye could pick out Dijon as the handsomest horse there. All the time she was talking and smiling her mind was methodically making its way through the options, the plusses and the minuses of her life. It would be highly dishonorable to marry Luke. He wanted a child, and she could not give him one. Except Cat, who would be safe and secure. No one would ever question who her real father was. Not quite true, they would wonder but it would make no difference. She would eventually be The O’Hara of Ballyhara, and the Countess of Fenton.

What kind of honor do I owe Luke? He has none himself, why should I feel he’s entitled to it from me?

Dijon won. John Morland was in transports. Everyone crowded around him, shouting and pounding on his back.

Under cover of the happy rowdiness, Scarlett turned to Luke Fenton. “Tell your solicitor to see mine about the contracts,” she said. “I choose late September for the wedding date. After Harvest Home.”

“Colum, I’m going to marry the Earl of Fenton,” said Scarlett.

He laughed. “And I’ll take Lilith for a bride. Such merrymaking there’ll be, with the legions of Satan for guests at the wedding feast.”

“It’s not a joke, Colum.”

His laughter stopped as if severed by a blade, and he stared at Scarlett’s pale, determined face. “I’ll not allow it,” he shouted. “The man’s a devil and an Anglo.”

Patches of red blotched Scarlett’s cheeks. “You . . . will . . . not . . . allow?” she said slowly. “You . . . will . . . not . . . allow? Who do you think you are, Colum? God?” She walked to him, eyes blazing, and thrust her face close to his. “Listen to me, Colum O’Hara, and listen good. Not you or anybody else on earth can talk to me like that. I won’t take it!”

His stare matched hers, and his anger, and they stood in stony confrontation for a timeless moment. Then Colum tilted his head to one side and smiled. “Ah, Scarlett darling, if it isn’t the O’Hara temper in the both of us, putting words we don’t mean in our two mouths. I’m begging your forgiveness, now; let’s talk this thing over.”

Scarlett stepped back. “Don’t charm me, Colum,” she said sadly, “I don’t believe it. I came to talk to my closest friend, and he’s not here. Maybe he never was.”

“Not so, Scarlett darling, not so!”

Her shoulders hunched in a brief, dejected shrug. “It doesn’t matter. I’ve made up my mind. I’m going to marry Fenton and move to London in September.”

“You’re a disgrace to your people, Scarlett O’Hara.” Colum’s voice was like steel.

“That’s a lie,” said Scarlett wearily. “Say that to Daniel, who’s buried in O’Hara land that was lost for hundreds of years. Or to your precious Fenians, who’ve been using me all this time. Don’t worry, Colum, I’m not going to give you away. Ballyhara will stay just as it is, with the inn for the men on the run, and the bars for you all to talk against the English in. I’ll make you bailiff for me, and Mrs. Fitz will keep the Big House going just the way it is. That’s really what you care about, not me.”

“No!” The cry burst from Colum’s lips. “Ach, Scarlett, you’re grievous wrong. You’re my pride and my delight, and Katie Colum holds my heart in her tiny hands. ’Tis only that Ireland is my soul and must be first.” He held out his hands to her in supplication. “Say you believe me, for I’m speaking the plain truth of it.”

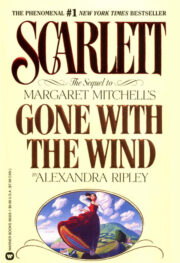

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.