“You look a bit shaken, Emma,” Mrs. Butler was saying. She and the stout woman touched cheeks, one side then the other. “Have a restful cup of tea, but first let me present Rhett’s wife, Scarlett.”

“It’ll take more than a cup of tea to repair my nerves after that little ride, Eleanor,” said the woman. She held out her hand. “How do you do, Scarlett? I’m Emma Anson, or rather what remains of Emma Anson.”

Eleanor embraced the younger woman and led her to Scarlett. “This is Margaret, dear, Ross’s wife. Margaret, meet Scarlett.”

Margaret Butler was a pale, fair-haired young woman with beautiful sapphire-blue eyes that dominated her thin colorless face. When she smiled, a network of deep, premature lines bracketed them. “I’m delighted to know you at last,” she said. She took Scarlett’s hands in hers and kissed her cheek. “I always wanted a sister, and a sister-in-law is practically the same thing. I hope you and Rhett will come to us for supper sometime soon. Ross will be longing to meet you, too.”

“I’d love to, Margaret, and I’m sure Rhett would, too,” said Scarlett. She smiled, hoping she was telling the truth. Who could say whether Rhett would escort her to his brother’s house or anyplace else? But it was going to be mighty hard for him to say no to his own family. Miss Eleanor and now Margaret were on her side. Scarlett returned Margaret’s kiss.

“Scarlett,” said Mrs. Butler, “do come meet Sally Brewton.”

“And Edward Cooper,” added a male voice. “Don’t deprive me of the chance to kiss Mrs. Butler’s hand, Eleanor. I’m already smitten.”

“Wait your turn, Edward,” Mrs. Butler said. “You young people have no manners at all.”

Scarlett hardly looked at Edward Cooper, and his flattery escaped her altogether. She was trying not to stare, but staring nonetheless at Sally Brewton, the monkey-faced driver of the carriage.

Sally Brewton was a tiny woman in her forties. She was shaped like a thin, active young boy, and her face did, in fact, greatly resemble a monkey’s. She wasn’t in the least upset by Scarlett’s rude stare. Sally was accustomed to the reaction; her remarkable ugliness—to which she had adapted long, long ago—and her unconventional behavior often astonished people who were strangers to her. She walked over to Scarlett now, her skirts trailing behind her like a brown river. “My dear Mrs. Butler, you must think us as mad as March hares. The truth is—boring though it may be—that there’s a perfectly rational explanation for our—shall we say?—dramatic arrival. I am the only surviving carriage possessor in town and I find it impossible to keep a coachman. They object to ferrying my dispossessed friends, and I insist on it. So I’ve given up hiring men who are going to quit almost at once. And—if my husband is otherwise occupied—I do the driving myself.” She put her small hand on Scarlett’s arm and looked up into her face. “Now I ask you, doesn’t that make perfectly good sense?”

Scarlett found her voice and said, “Yes.”

“Sally, you mustn’t trap poor Scarlett like that,” said Eleanor Butler. “What else could she say? Tell her the rest.”

Sally shrugged, then grinned. “I suppose your mother-in-law is referring to my bells. Cruel creature. The fact is that I am an appallingly bad driver. So whenever I take the carriage out, I’m required by my humanitarian husband to bedeck it in bells, as advance warning to people to get out of my way.”

“Rather like a leper,” offered Mrs. Anson.

“I shall ignore that,” Sally said with an air of injured dignity. She smiled at Scarlett, a smile of such genuine good will that Scarlett felt warmed by it. “I do hope,” she said, “that you’ll call on me whenever you need the brougham, despite what you’ve seen.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Brewton, you’re very kind.”

“Not at all. The fact is, I adore careening through the streets, scattering scallywags and carpetbaggers to the four winds. But I’m monopolizing you. Let me present Edward Cooper before he expires . . .”

Scarlett responded automatically to the gallantries of Edward Cooper, smiling to create the beguiling dimple at the corner of her mouth and shamming embarrassment at his compliments while inviting more of them with her eyes. “Why, Mr. Cooper,” she said, “how you do run on. I declare you’re liable to turn my head. I’m just a country girl from Clayton County, Georgia, and I don’t know what to make of a sophisticated Charleston gentleman like you.”

“Miss Eleanor, please forgive me,” she heard a new voice say. Scarlett turned and drew in a sharp breath. There was a girl in the doorway, a young girl with shining brown hair that grew in a widow’s peak above her soft brown eyes. “I’m so sorry to be late,” the girl continued. Her voice was soft, a little breathless. She was wearing a brown dress with white linen collar and cuffs and an old-fashioned bonnet covered in brown silk.

She looks for all the world like Melanie when I first knew her, Scarlett thought. Like a soft little brown bird. Could she be a cousin? I never heard the Hamiltons had any kin in Charleston.

“You’re not late at all, Anne,” said Eleanor Butler. “Come have some tea, you looked chilled to the bone.”

Anne smiled gratefully. “The wind is picking up, and the clouds are coming in fast. I believe I beat the rain by only a few steps . . . Good afternoon, Miss Emma, Miss Sally, Margaret, Mr. Cooper.” She stopped, her lips parted, her eyes on Scarlett. “Good afternoon. I don’t think we’ve met. I’m Anne Hampton.”

Eleanor Butler hurried to the girl’s side. She was holding a steaming cup. “How barbaric of me,” she exclaimed. “I was so busy with the tea that I forgot that of course you don’t know Scarlett, my daughter-in-law. Here, Anne, drink this at once. You’re white as a ghost . . . Scarlett, Anne is our expert on the Confederate Home. She graduated from the school last year, and now she’s teaching there. Anne Hampton—Scarlett Butler.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Butler.” Anne extended a cold little hand. Scarlett felt it quiver in her own warm one when she shook it.

“Please call me Scarlett,” she said.

“Thank you . . . Scarlett. I’m Anne.”

“Tea, Scarlett?”

“Thank you, Miss Eleanor.” She hurried to take the cup, glad to escape from the confusion she felt when she looked at Anne Hampton. She’s Melly to the life. Just as frail, just as mousy, just as sweet—I can tell that already. She must be an orphan if she’s at that Home place. Melanie was an orphan, too. Oh, Melly, how I miss you.

The sky was darkening outside the windows. Eleanor Butler asked Scarlett to draw the curtains when she finished her tea.

As she drew the curtains on the last window, she heard a rumbling of thunder in the distance and a spattering of rain on the glass.

“Let’s come to order,” said Miss Eleanor. “We’ve got a lot of business to do. Everyone take a seat. Margaret, will you keep passing the tea cakes and sandwiches? I don’t want anyone distracted by an empty stomach. Emma, you’ll continue to pour, won’t you? I’ll ring for more hot water.”

“Let me go get it, Miss Eleanor,” said Anne.

“No, dear, we need you here. Scarlett, just pull that bell rope, please, my dear. Now, ladies and gentleman, the first order of business is very exciting. I’ve received a large check from a lady in Boston. What shall we do with it?”

“Tear it up and send the pieces back to her.”

“Emma! Is your brain asleep? We need all the money we can get. Besides, the donor is Patience Bedford. You remember her. We used to see her and her husband almost every year at Saratoga in the old days.”

“Wasn’t there a General Bedford in the Union Army?”

“There was not. There was a General Nathan Bedford Forrest in our army.”

“The finest cavalryman we had,” said Edward.

“I don’t think Ross would agree with that, Edward.” Margaret Butler put a plate of bread and butter down with a clatter. “After all, he was in the cavalry with General Lee.”

Scarlett yanked the bell rope a second time. Great balls of fire! Did all Southerners have to refight the War every time they met? What difference did it make if the money came from Ulysses Grant himself? Money was money, and you took it anywhere you found it.

“Truce!” Sally Brewton waved a white napkin in the air. “If you would give Anne an opening, she’s trying to say something.”

Anne’s eyes were glowing with emotion. “I’ve got nine little girls that I’m teaching to read, and only one book to teach from. If the ghost of Abe Lincoln came and offered to buy us some books, I’d—I’d kiss him!”

Good for you, cheered Scarlett silently. She looked at the astonishment on the faces of the other women. Edward Cooper’s expression was something quite different. Why, he’s in love with her, she thought. Just see the way he’s looking at her. And she doesn’t notice him at all, she doesn’t even know he’s yearning over her like a moon calf. Maybe I should tell her. He’s really quite attractive if you like the type, sort of slender and dreamy-looking. Not all that different from Ashley, come to think of it.

Sally Brewton was watching Edward, too, Scarlett noticed. Sally’s eyes met hers and they exchanged discreet smiles.

“We’re agreed, then, are we?” said Eleanor. “Emma?”

“We’re agreed. Books are more important than rancor. I’m being over-emotional. It must be dehydration. Is anyone ever going to bring that hot water?”

Scarlett rang again. Maybe the bell was broken; should she go down to the kitchen and tell the servants? She started from the corner, then saw the door opening.

“Did you ring for tea, Mrs. Butler?” Rhett pushed the door wider with his foot. His hands were holding a huge silver tray laden with gleaming tea pot, urn, bowl, sugar bowl, milk pitcher, strainer, and three tea caddies. “India, China, or chamomile?” He was smiling with delight at his surprise.

Rhett! Scarlett couldn’t breathe. How handsome he was. He’d been in the sun somewhere, he was brown as an Indian. Oh, God, how she loved him, her heart was beating so hard that everyone must be able to hear it.

“Rhett! Oh, darling, I’m afraid I’m going to make a spectacle of myself.” Mrs. Butler grabbed a napkin and wiped her eyes. “You said ‘some silver’ in Philadelphia. I had no idea it was the tea service. And intact. It’s a miracle.”

“It’s also very heavy. Miss Emma, will you please push that makeshift china to one side? I heard you mention something about thirst, I believe. I’d be honored if you’d brew your heart’s desire . . . Sally, my beloved, when are you going to agree to let me duel your husband to the death and abduct you?” Rhett placed the tray on the table, leaned across it, and kissed the three women sitting on the settee behind it. Then he looked around.

Look at me, Scarlett begged silently from the shadowy corner. Kiss me.

But he didn’t see her. “Margaret, how lovely you look in that gown. Ross doesn’t deserve you. Hello, Anne, it’s a pleasure to see you. Edward, I can’t say the same for you. I don’t approve of your organizing yourself a harem in my house when I’m out in the rain in the sorriest hansom cab in North America, clutching the family silver to my bosom to protect it from the carpetbaggers.” Rhett smiled at his mother. “Stop that crying, now, Mama dear,” he said, “or I’ll think you don’t like your surprise.”

Eleanor looked up at him, her face shining with love. “Bless you, my son. You make me very happy.”

Scarlett couldn’t stand another minute of it. She ran forward. “Rhett, darling—”

His head turned toward her, and she stopped. His face was rigid, blank, all emotion withheld by an iron control. But his eyes were bright; they faced one another for a breathless moment. Then his lips turned downward at one corner in the sardonic smile she knew so well and feared so much. “It’s a fortunate man,” he said slowly and clearly, “who receives a greater surprise than he gives.” He held his hands out for hers. Scarlett put her trembling fingers into his palms, conscious of the distance his outstretched arms kept between them. His mustache brushed her right cheek, then her left.

He’d like to kill me, she thought, and the danger of it gave her a strange thrill. Rhett put his arm around her shoulders, his hand clamped like a vise around her upper arm.

“I’m sure you ladies—and Edward—will excuse us if we leave you,” he said. There was an appealing mixture of boyishness and roguishness in his voice. “It’s been much too long since I’ve had a chance to talk to my wife. We’ll go upstairs and leave you to solve the problems of the Confederate Home.”

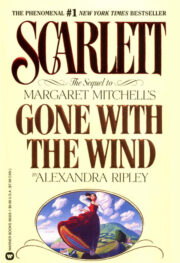

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.