She tried to keep her mind on what Rhett’s mother was saying, but she couldn’t. She didn’t care about the Confederate Home for Widows and Orphans. Her fingers touched the bodice of her dress, but there were no cascades of lace to fiddle with. Surely he wouldn’t care about her clothes if he really didn’t care about her, would he?

“. . . so the school just sort of grew by itself because there was no place else really for the orphans to go,” Mrs. Butler was saying. “It’s been more successful than we would have dared to hope. Last June, there were six graduated, all of them teachers now themselves. Two of the girls have gone to Walterboro to teach, and one actually had a choice of places, either Yemassee or Camden. Another one—such a sweet girl—wrote to us, I’ll show you the letter . . .”

Oh, where is he? What could be taking him so long? If I have to sit still much longer, I’ll scream.

The bronze clock on the mantel chimed and Scarlett jumped. Two . . . three . . . “I wonder what’s keeping Rhett?” said his mother. Five . . . six. “He knows we have supper at seven, and he always enjoys a toddy first. He’ll be soaked to the skin, too; he’ll have to change his clothes.” Mrs. Butler put her tatting down on the table at her side. “I’ll just go see if the rain’s stopped,” she said.

Scarlett leapt to her feet. “I’ll go.” She walked quickly, released, and pulled back an edge of the heavy silk curtain. Outside a heavy mist was billowing over the sea-wall promenade. It swirled in the street and coiled upward like a live thing. The street lamp was a glowing, undefined brightness in the moving whiteness surrounding it. She drew back from the eerie formlessness and dropped the silk over the sight of it. “It’s all foggy,” she said, “but it’s not raining. Do you think Rhett’s all right?”

Eleanor Butler smiled. “He’s been through worse than a little wet and fog, Scarlett, you know that. Of course he’s all right. You’ll hear him at the door any minute now.”

As if the words had caused it, there came the sound of the great front door opening. Scarlett heard Rhett’s laughter and the deep voice of Manigo, the butler.

“You best hand me them wet things, Mist’ Rhett, boots, too. I got your house shoes right here,” Manigo was saying.

“Thank you, Manigo. I’ll go up and change. Tell Mrs. Butler I’ll be with her in a minute. Is she in the drawing room?”

“Yessir, her and Missus Rhett.”

Scarlett listened for Rhett’s reaction, but she heard only his quick firm tread on the steps. It seemed a century before he came back down. The clock on the mantel had to be wrong. Each minute took an hour to pass.

“You look tired, dear,” exclaimed Eleanor Butler when Rhett entered the drawing room.

Rhett lifted his mother’s hand and kissed it. “Don’t cluck over me, Mama, I’m more hungry than tired. Supper soon?”

Mrs. Butler started to rise. “I’ll tell the kitchen to serve right now.” Rhett gently touched her shoulder to halt her effort.

“I’ll have a drink first, don’t rush.” He walked to the table holding the drinks tray. As he poured whiskey into a glass, he looked at Scarlett for the first time. “Will you join me, Scarlett?” His raised eyebrow taunted her. So did the smell of the whiskey. She turned away, as if insulted. So, Rhett was going to play cat and mouse, was he? Try to force her or trick her into doing something that would make his mother turn against her. Well, he’d have to be mighty smart to catch her out. Her mouth curved and her eyes began to sparkle. She’d have to be mighty smart herself to outwit him. A little pulse of excitement throbbed in her throat. Competition always thrilled her.

“Miss Eleanor, isn’t Rhett shocking?” she laughed. “Was he a wicked little boy, too?” Behind her she sensed Rhett’s abrupt movement. Ha! That had struck home. He’d felt guilty for years about the pain he’d caused his mother when his escapades made his father disown him.

“Supper’s served, Miz Butler,” said Manigo from the doorway.

Rhett offered his mother his arm, and Scarlett felt a stab of jealousy. Then she reminded herself that his devotion to his mother was the very thing that permitted her to stay, and she swallowed her anger. “I’m so hungry I could eat half a cow,” she said, her voice bright, “and Rhett’s just starving, aren’t you, darling?” She had the upper hand now; he had admitted that much. If she lost it, she’d lose the whole game, she’d never get him back.

As it turned out, Scarlett needn’t have worried. Rhett took command of the conversation the moment they were seated. He recounted his search for the tea service in Philadelphia, transforming it into an adventure, painting deft word portraits of the succession of people he talked to, mimicking their accents and idiosyncrasies with such skill that his mother and Scarlett found themselves laughing until their sides ached.

“And after following that long trail to get to him,” Rhett concluded with a theatrical gesture of dismay, “just imagine my horror when the new owner seemed to be too honest to sell the tea service for the twenty times its value I offered. For a minute, I was afraid I’d have to steal it back, but fortunately he was receptive to the suggestion that we amuse ourselves with a friendly game of cards.”

Eleanor Butler tried to look disapproving. “I do hope you didn’t do anything dishonest, Rhett,” she said. But there was laughter beneath the words.

“Mama! You shock me. I only deal from the bottom when I’m playing with professionals. This miserable ex-colonel in Sherman’s army was such an amateur I had to cheat to let him win a few hundred dollars to ease his pain. He was like the reverse side of an Ellinton.”

Mrs. Butler laughed. “Oh, the poor man. And his wife—my heart goes out to her.” Rhett’s mother leaned toward Scarlett. “Some of the skeletons in my side of the family,” Eleanor Butler said in a mock whisper. She laughed again and began to reminisce.

The Ellintons, Scarlett learned, were famous all up and down the East Coast for the family weakness: they would gamble on anything. The first Ellinton to settle in Colonial America was part of the shipload only because he had won a land grant in a wager with the owner as to who could drink the most ale and remain standing. “By the time he won,” Mrs. Butler said, in neat conclusion, “he was so drunk that he thought it made sense to go take a look at his prize. They say he didn’t even know where he was going until he got there, because he won most of the sailors’ rum ration playing dice.”

“What did he do when he sobered up?” Scarlett wanted to know.

“Oh, my dear, he never did. He died only ten days after the ship made landfall. But in the meantime he had wagered some other gambler at dice and won a girl—one of the indentured servants from the ship—and, since later she turned out to be carrying his child, there was a sort of ex post facto wedding at his grave marker, and her son became one of my great-great-grandfathers.”

“He was rather a gamester himself, wasn’t he?” Rhett asked.

“Oh, of course. It truly ran in the family.” And Mrs. Butler continued along the family tree.

Scarlett glanced at Rhett often. How many surprises were there in this man she hardly knew? She’d never seen him so relaxed and happy and totally at home. I never made a home for him, she realized. He never even liked the house. It was mine, done the way I wanted, a present from him, not his at all. Scarlett wanted to break in on Miss Eleanor’s stories, to tell Rhett that she was sorry for the past, that she’d make up for all her mistakes. But she kept silent. He was content, enjoying himself and his mother’s ramblings. She mustn’t break this mood.

The candles in their tall silver holders were reflected in the polish of the mahogany table and in the pupils of Rhett’s gleaming black eyes. They bathed the table and the three of them in a warm, still light, making an island of soft brilliance in the shadows of the long room. The world outside was closed off by the thick folds of curtains at the windows and by the intimacy of the small candlelit island. Eleanor Butler’s voice was gentle, Rhett’s laughter a quiet, encouraging chuckle. Love made an airy yet unbreakable web between mother and son. Scarlett had a sudden consuming yearning to be enclosed in that web.

Then Rhett said, “Tell Scarlett about Cousin Townsend, Mama,” and she was safe in the warmth of the candlelight, included in the happiness that ringed the table. She wished that it could last forever, and she begged Miss Eleanor to tell about Cousin Townsend.

“Townsend’s not really a cousin-cousin, you know, only a third cousin twice removed, but he is the direct descendent of Great-Great-Grandfather Ellinton, only son of an eldest son of an eldest son. So he inherited that original land grant, and the Ellinton gambler’s fever, and the Ellinton luck. They were always lucky, the Ellintons. Except for one thing: there’s another Ellinton family trait, the boys are always cross-eyed. Townsend married an extremely beautiful girl from a fine Philadelphia family—Philadelphia called it the wedding of beauty and the beast. But the girl’s father was a lawyer and a very sensible man about property, and Townsend was fabulously rich. Townsend and his wife settled in Baltimore. Then, of course, the War came. Townsend’s wife went running home to her family the minute Townsend went off to join General Lee’s army. She was a Yankee, after all, and Townsend would more than likely get killed. He couldn’t shoot a barn, much less a barn door, because of his cross eyes. However, he still had the Ellinton luck. He never got anything worse than chilblains although he served all the way through to Appomattox. Meanwhile, his wife’s three brothers and her father were all killed, fighting in the Union Army. So she inherited everything piled up by her careful father and his careful ancestors. Townsend’s living like a king in Philadelphia and doesn’t care a fig that all his property in Savannah was confiscated by Sherman. Did you see him, Rhett? How is he?”

“More cross-eyed than ever, with two cross-eyed sons and a daughter that, thank God, takes after her mother.”

Scarlett hardly heard Rhett’s answer. “Did you say the Ellintons were from Savannah, Miss Eleanor? My mother was from Savannah,” she said eagerly. The crisscross of relations that was so much a part of Southern life had long been a frustrating lack in her own. Everyone she knew had a network of cousins and uncles and aunts that covered generations and hundreds of miles. But she had none. Pauline and Eulalie had no children. Gerald O’Hara’s brothers in Savannah were childless, too. There must be lots of O’Haras still in Ireland, but that did her no good, and all the Robillards except her grandfather were gone from Savannah.

Now here she was, again hearing about somebody else’s family. Rhett had kin in Philadelphia. No doubt he was related to half of Charleston, too. It wasn’t fair. But maybe these Ellinton people were tied to the Robillards somehow. Then she’d be part of the web that included Rhett. Perhaps she could find a connection to the world of the Butlers and Charleston, the world that Rhett had chosen and she was determined to enter.

“I remember Ellen Robillard very well,” said Mrs. Butler. “And her mother. Your grandmother, Scarlett, was probably the most fascinating woman in all of Georgia, and South Carolina, too.”

Scarlett leaned forward, enthralled. She’d heard only bits and pieces of stories about her grandmother. “Was she really scandalous, Miss Eleanor?”

“She was extraordinary. But when I knew her best, she wasn’t scandalous at all. She was too busy having babies. First your Aunt Pauline, then Eulalie, then your mother. As a matter of fact, I was in Savannah when your mother was born. I remember the fireworks. Your grandfather hired some famous Italian to come down from New York and put on a magnificent fireworks display every time your grandmother gave him a baby. You wouldn’t remember, Rhett, and I don’t suppose you’ll thank me for remembering, either, but you were scared witless. I took you outside especially to see them, and you cried so loud that I nearly died of shame. All the other children there were clapping their hands and shrieking with joy. Of course, they were older. You were still in dresses, barely over a year old.”

Scarlett stared at Mrs. Butler, then at Rhett. It wasn’t possible! Rhett couldn’t be older than her mother. Why, her mother was—her mother. She’d always taken it for granted that her mother was old, past the age of strong emotions. How could Rhett be older? How could she love him so desperately if he was that old?

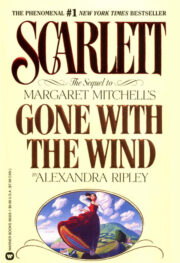

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.