“Where’d Rhett get his name?”

“He’s named after our grandfather.”

“Rhett told me your grandfather was a pirate.”

“He did?” Rosemary laughed. “He would say that. Granddaddy ran the English blockade in the Revolution just like Rhett ran the Yankee blockade in our war. He was bound and determined to get his rice crop out, and he wouldn’t let anything stop him. I imagine he did some pretty sharp trading on the side, but mainly he was a rice planter. Dunmore Landing has always been a rice plantation. That’s why I get so mad at Rhett—”

Scarlett rocked faster. If she starts going on about rice again, I’ll scream.

The loud double report of a shotgun crashed through the night and Scarlett did scream. She jumped up from the chair and ran toward the door. Rosemary leapt up and ran after her. She threw her strong arms around Scarlett’s middle and held her back.

“Let me go, Rhett might be—” Scarlett croaked.

Rosemary was squeezing the breath out of her. Rosemary’s arms tightened. Scarlett struggled to get free. She heard her own strangled breath loud in her ears and—strangely more distinct—the creak creak creak of the rocker, slowing even as her breath was slowing. The lighted room seemed to be turning dark.

Her flailing hands fluttered weakly and her straining throat made a faint rasping noise. Rosemary let her go. “I’m sorry,” Scarlett thought she heard Rosemary say. It didn’t matter. The only thing that mattered was to draw great gulps of air into her lungs. It even made no difference that she’d fallen onto her hands and knees. It was easier to breathe that way.

It was a long time before she could speak. She looked up then, saw Rosemary standing with her back against the door. “You almost killed me,” Scarlett said.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to hurt you. I had to stop you.”

“Why? I was going to Rhett. I’ve got to go to Rhett.” He meant more to her than all the world. Couldn’t this stupid girl understand that? No, she couldn’t, she’d never loved anybody, never had anybody love her.

Scarlett tried to scrabble to her feet. Oh, sweet Mary, Mother of God, I’m so weak. Her hands found the bedpost. Slowly she pulled herself upright. She was as white as a ghost, her green eyes blazed like cold flames.

“I’m going to Rhett,” she said.

Rosemary struck her then. Not with her hands or even her fists. Scarlett could have withstood that.

“He doesn’t want you,” Rosemary said quietly. “He told me so.”

24

Rhett paused in mid-sentence. He looked at Scarlett and said, “What is this? No appetite? And they say that country air is supposed to make people hungry. You astonish me, my dear. I do believe this is the first time I’ve ever seen you peck at your food.”

She looked up from her untouched plate to glare at him. How did he even dare to speak to her when he had been talking about her behind her back? Who else had he talked to besides Rosemary? Did everybody in Charleston know that he had walked out in Atlanta and that she’d made a fool of herself by coming after him?

She looked down and continued to push bits of food from place to place.

“So then what happened?” Rosemary demanded. “I still don’t understand.”

“It was just what Miss Julia and I expected. Her field hands and my phosphate diggers had cooked up a plot. You know that work contracts are signed on New Year’s Day for the year to follow. Miss Julia’s men were going to tell her that I paid my miners almost twice what she paid and that she’d have to jack up their salaries or they’d come to me. My men were going to play the same game, only the other way around. It never entered their heads that Miss Julia and I were on to them.

“The grapevine started humming the minute we rode over to Ashley Barony. All of them knew the game was up. You saw how industrious all the Barony workers were in the rice fields. They didn’t want to risk losing their jobs, and they’re all scared to death of Miss Julia.

“Things weren’t quite that smooth here. Word had gotten out that the Landing blacks were scheming something, and the white sharecroppers across the Summerville road got edgy. They did what poor whites always do, grabbed their guns and got ready for a little shooting. They came to the house and broke in and stole my whiskey, then passed the bottle around to get up a good head of steam. After you were safely out of range I told them I’d take care of my business myself, and I high-tailed it out to the back of the house. The blacks were scared, as well they might be, but I persuaded them that I could calm the whites down and that they should go home.

“When I got back to the house, I told the sharecroppers that I’d settled everything with the workers and they should go on home, too. I probably gave it to them too fast. I was so relieved myself that there hadn’t been any trouble that it made me careless. I’ll be smarter next time. If, God forbid, there is a next time. Anyhow, Clinch Dawkins flew off the handle. He was looking for trouble. He called me a nigger lover and cocked that cannon of a shotgun he’s got and turned it in my direction. I didn’t wait to find out if he was drunk enough to shoot, I just stepped over and knocked it up. The sky got a couple of holes in it.”

“Is that all?” Scarlett half-shouted. “You could have let us know.”

“I was too busy, my pet. Clinch’s pride was wounded, so he pulled a knife. I pulled mine and we had an active ten minutes or so before I cut off his nose.”

Rosemary gasped.

Rhett patted her hand. “Only the end of it. It was too long anyhow. His looks are significantly improved.”

“But Rhett, he’ll come after you.”

Rhett shook his head. “No, I can assure you he won’t. It was a fair fight. And Clinch is one of my oldest companions. We were in the Confederate Army together. He was loader for the cannon I commanded. There’s a bond between us that a small slice of nose can’t damage.”

“I wish he’d killed you,” said Scarlett distinctly. “I’m tired and I’m going to bed.” She pushed her chair back and walked with a dignified tread from the room.

Rhett’s words, deliberately drawled, followed her. “No greater blessing can be granted a man than the devotion of a loving wife.”

Scarlett’s heart grew hot with anger. “I hope Clinch Dawkins is outside this house right this minute,” she muttered, “just waiting for a clean shot.”

For that matter, she wouldn’t exactly cry her eyes out if the second barrel got Rosemary.

Rosemary lifted her wine glass to Rhett in a salute. “All right, now I know why you said supper was a celebration. I, for one, am celebrating this day being over.”

“Is Scarlett sick?” Rhett asked his sister. “I was only half-joking about her appetite. It’s not like her not to eat.”

“She’s upset.”

“I’ve seen her upset more times than you can count, and she’s eaten like a longshoreman every time.”

“This isn’t just her temper, Rhett. While you were chopping noses, Scarlett and I had a wrestling match ourselves.” Rosemary described Scarlett’s panic and her determination to go to him. “I didn’t know how dangerous things might be downstairs, so I held her back. I hope I did right.”

“You did absolutely right. Anything could have happened.”

“I’m afraid I held a little too tight,” Rosemary confessed. “She almost passed out, she couldn’t breathe.”

Rhett threw his head back and laughed. “By God, I wish I’d seen that. Scarlett O’Hara pinned to the mat by a girl. There must be a hundred women in Georgia who would have clapped the skin off their hands applauding you!”

Rosemary considered confessing the rest. She realized that what she’d said to Scarlett had hurt her more than the fight. She decided not to. Rhett was still chuckling; no sense in dimming his good mood.

Scarlett woke before dawn. She lay motionless in the dark room, afraid to move. Breathe like you’re still asleep, she told herself, you wouldn’t wake up in the middle of the night unless there’d been a noise or something. She listened for what seemed like an eternity, but the silence was heavy and unbroken.

When she realized that it was hunger that had wakened her, she almost cried with relief. Of course she was hungry! She’d had nothing to eat since breakfast the day before, except for a few tea sandwiches at Ashley Barony.

The night air was too cold for her to wear the elegant silk dressing gown she’d brought with her. She wrapped herself in the coverlet from the bed. It was heavy wool and still held in it the warmth of her body. It trailed awkwardly around her bare feet as she crept quietly through the dark hallway and down the stairs. Thank goodness, the banked fire in the great fireplace gave out some heat still, and enough light for her to see the door to the dining room and the kitchen beyond. She didn’t care what she might find; even cold rice and stew would be all right. With one hand holding the dark coverlet around her, she groped for the doorknob. Was it to the left or the right? She hadn’t noticed.

“Stop right there, or I’ll blow a hole through your middle!” Rhett’s harsh voice made her jump. The blanket fell away and cold air assaulted her.

“Great balls of fire!” Scarlett turned on him and bent to gather up the folds of wool. “Didn’t I have enough to scare me witless yesterday? Do you have to start up again? You nearly made me jump out of my skin!”

“What are you doing wandering around at this hour, Scarlett? I could have shot you.”

“What are you doing skulking around scaring people?” Scarlett draped the coverlet around her shoulders as if it were an imperial robe of ermine. “I’m going to the kitchen to get some breakfast,” she said with all the dignity she could muster.

Rhett smiled at the absurdly haughty figure she cut. “I’ll make up the fire in the stove,” he said. “I was thinking of some coffee myself.”

“It’s your house. I reckon you can have coffee if you want some.” Scarlett kicked the trailing coverlet behind her as if it were the train on a ball gown. “Well? Aren’t you going to open the door for me?”

Rhett threw some logs into the fireplace. The hot coals touched off a flare of dried leaves on one branch of wood. He quickly sobered the expression on his face before Scarlett could see it. He opened the door to the dining room and stepped back. Scarlett swept past him, but had to stop almost at once. The room was completely dark.

“If you’ll allow me—” Rhett struck a match. He touched it to the lamp above the table, then carefully adjusted the flame.

Scarlett could hear the laughter in his voice but somehow it didn’t make her angry. “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse,” she admitted.

“Not a horse, please,” Rhett laughed. “I’ve only got three, and two of them are no damn good.” He settled the glass chimney on the lamp and smiled down at her. “How about some eggs and a slice of ham?”

“Two slices,” said Scarlett. She followed him into the kitchen and sat on a bench by the table with her feet tucked up under the blanket while he lit a fire in the big iron stove. When the pine kindling was crackling, she stretched her feet out to the warmth.

Rhett brought a half-eaten ham and bowls of butter and eggs from the pantry. “The coffee grinder’s on the table behind you,” he said. “The beans are in that can. If you’ll grind some while I slice the ham, breakfast will be ready that much sooner.”

“Why don’t you grind them while I cook the eggs?”

“Because the stove’s not hot yet, Miss Greedy. There’s a pan of cold corn bread next to the grinder. That should tide you over. I’ll do the cooking.”

Scarlett swivelled around. The pan under the napkin had four squares of corn bread left in it. She dropped her wrap to reach for a piece. While she was chewing she put a handful of coffee beans into the grinder. Then she alternated taking bites of corn bread with turning the handle. When the corn bread was almost gone, she heard the sizzle as Rhett dropped ham slices into a skillet.

“That smells like heaven,” she said happily. She finished grinding the coffee with a spurt of rapid cranks. “Where’s the coffee pot?” She turned, saw Rhett, and began to laugh. He had a dishtowel tucked into the waistband of his trousers and a long fork in one hand. He waved the fork in the direction of a shelf by the door.

“What’s so funny?”

“You. Dodging the fat spatters. Cover the stove hole or you’ll set the whole pan on fire. I should have known you wouldn’t know what to do.”

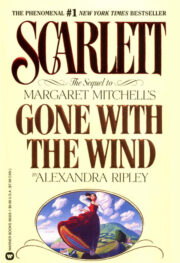

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.