“Nonsense, madam. I prefer the adventure of the open flame. It takes me back to the delightful days of frying fresh buffalo steaks at a campfire.” But he slid the skillet to one side of the opening in the stove top.

“Did you really eat buffalo? In California?”

“Buffalo and goat and mule—and the meat off the dead body of the person who didn’t make the coffee when I wanted it.”

Scarlett giggled.

She ran across the cold stone floor to get the pot. They ate silently at the kitchen table, both concentrating hungrily on the food. It was warm and friendly in the dark room. An open door on the stove gave an uneven reddish light. The smell of coffee brewing on the stove was dark and sweet. Scarlett wanted the breakfast to last forever. Rosemary must have lied. Rhett couldn’t have told her he didn’t want me.

“Rhett?”

“Hmm?” He was pouring the coffee.

Scarlett wanted to ask him if the comfort and laughter could last, but she was afraid it would ruin everything. “Is there any cream?” she asked instead.

“In the pantry. I’ll get it. Keep your feet warm by the stove.”

He was gone only a few seconds.

While she stirred sugar and cream into her coflee, she stirred up her nerve. “Rhett?”

“Yes?”

Scarlett’s words tumbled out in a burst, quickly so that he couldn’t stop her. “Rhett, can’t we have good times like this forever? This is a good time, you know it is. Why do you have to keep acting as though you hate me?”

Rhett sighed. “Scarlett,” he said wearily, “any animal will attack if it’s cornered. Instinct is stronger than reason, stronger than will. When you came to Charleston, you were backing me into a corner. Crowding me. You’re doing it now. You can’t leave well enough alone. I want to be decent. But you won’t let me.”

“I will, I will let you. I want you to be—”

“You don’t want kindness, Scarlett, you want love. Unquestioning, undemanding, unequivocal love. I gave you that once, when you didn’t want it. I used it all up, Scarlett.” Rhett’s tone was growing colder, edged with harsh impatience. Scarlett shrank away from it, unconsciously touching the bench at her side, trying to find the warmth of the discarded coverlet.

“Let me put it in your terms, Scarlett. I had in my heart a thousand dollars’ worth of love. It was in gold, not greenbacks. And I spent it on you, every penny of it. As far as love is concerned, I’m bankrupt. You’ve wrung me dry.”

“I was wrong, Rhett, and I’m sorry. I’m trying to make up for it.” Scarlett’s mind was racing frantically. I can give him my heart’s thousand dollars’ worth of love, she thought. Two thousand, five, twenty, a thousand thousand. Then he’ll be able to love me because he won’t be bankrupt any more. He’ll have it all back, and more. If he’ll just take it. I have to make him take it . . .

“Scarlett,” Rhett was saying, “there’s no ‘making up’ for the past. Don’t destroy the little that is left. Let me be kind, I’ll feel better for it.”

She seized on his words. “Oh, yes! Yes, Rhett, please. Be kind, the way you were before I ruined the happy time we were having. I won’t crowd you. Let’s just have fun, be friends, until I go back to Atlanta. I’ll be content if we can just laugh together; I had such a good time at breakfast. My, you are a sight in that apron thing.” She giggled. Thank God he couldn’t see her any better than she could see him.

“That’s all you want?” Relief took the edge from Rhett’s voice. Scarlett took a big swallow of coffee while she planned what to say. Then she managed an airy laugh.

“Well, of course, silly. I know when I’m beat. I figured it was worth a try, that’s all. I won’t crowd you any more, but please make the Season good for me. You know how much I love parties.” She laughed again. “And if you really want to be kind, Rhett Butler, you can pour me another cup of coffee. I don’t have a hot-holder, and you do.”

After breakfast Scarlett went upstairs to get dressed. It was still night, but she was much too excited to think about going back to sleep. She’d patched things up pretty well, she thought. His guard was down. He had enjoyed their breakfast, too, she was sure of it.

She put on the brown travelling costume she had worn on the boat to the Landing, then brushed her dark hair back from her temples and tucked combs in to hold it. Then she rubbed just a small amount of eau de cologne across her wrists and throat, just a whiff reminder that she was feminine and soft and desirable.

Walking along the hall and down the stairs she was as quiet as she could be. The longer Rosemary stayed asleep, the better. The east-facing window on the stair landing was distinct in the darkness. It was nearly dawn. Scarlett blew out the flame in the lamp she was carrying. Oh, please let this be a good day, let me do everything right. Let it be like breakfast all day long. And all night after. It’s New Year’s Eve.

The house had the special quality of quiet that wraps the earth just before sunrise. Scarlett stepped carefully to make no noise until she reached the center room below. The fire was burning brightly; Rhett must have put more logs on while she was dressing. She could just make out the dark shape of his shoulders and head framed by the gray semi-light of a window beyond him. He was in his office with the door ajar, his back to her. She tiptoed across the room and tapped gently on the door frame with the tips of her fingers. “May I come in?” she whispered.

“I thought you’d gone back to bed,” said Rhett. He sounded very tired. She remembered that he’d been up all night guarding the house. And her. She wished she could cradle his head against her heart and stroke his tiredness away.

“There wasn’t much point to going to sleep, there’ll be roosters crowing like crazy as soon as the sun’s up.” She put one foot tentatively across the doorsill. “Is it all right if I sit in here? There’s not such a reek in your office.”

“Come in,” Rhett said without looking at her.

Scarlett moved quietly to a chair just inside the office. Over Rhett’s shoulder she could see the window becoming more distinct. I wonder what he’s looking for so hard. Are those Crackers outside again? Or Clinch Dawkins? A cock crowed, and her whole body jerked.

Then the first weak rays of red dawn light touched the scene outside the window. The jagged tumbled brick ruins of Dunmore Landing’s house were dramatically lit, red against the dark sky behind them. Scarlett cried out. It looked as if they were still smoldering. Rhett was watching the death throes of his home.

“Don’t look, Rhett,” she begged, “don’t look. It will only break your heart.”

“I should have been here, I might have stopped them.” Rhett’s voice was slow, distant, as if he didn’t know that he was speaking.

“You couldn’t have. There must have been hundreds of them. They would have shot you and burned everything anyhow!”

“They didn’t shoot Julia Ashley,” said Rhett. But he sounded different now. There was a glimmer of wryness, almost humor, beneath his words. The red light outside was changing, becoming more golden, and the ruins were only blackened bricks and chimneys with the sun-touched sheen of dew on them.

Rhett’s swivel chair swung around. He rubbed his hand over his chin, and Scarlett could almost hear the rasp of the unshaven whiskers. He had shadows under his eyes, visible even in the shadowy room, and his black hair was dishevelled, a cowlick standing up on the crown, an untidy lock falling on his forehead. He stood, yawned, and stretched. “I believe it’s safe to sleep a little now. You and Rosemary stay in the house till I wake up.” He lay down on a wooden bench and fell asleep at once.

Scarlett watched him as he slept.

I mustn’t ever tell him again that I love him. That makes him feel pressured. And when he turns nasty, I feel small and cheap for having said it. No, I’ll never say it again, not until he’s told me first that he loves me.

25

Rhett was busy from the moment he woke after an hour’s heavy sleep, and he told Rosemary and Scarlett bluntly to keep away from the butterfly lakes. He was building a platform there for the speeches and hiring ceremonies the next day. “Working men don’t take kindly to the presence of women.” He smiled at his sister. “And I certainly don’t want Mama asking me why I permitted you to learn such a colorful new vocabulary.”

At Rhett’s request, Rosemary led Scarlett on a tour of the overgrown gardens. The paths had been cleared but not gravelled, and Scarlett’s hem was soon black from fine dust. How different everything was from Tara, even the soil. It seemed unnatural to her that the paths and the dust weren’t red. The vegetation was so thick, too, and many of the plants were unfamiliar. It was too lush for her upland taste.

But Rhett’s sister loved the Butler plantation with a passion that surprised her. Why, she feels about this place just the way I feel about Tara. Maybe I can get along with her after all.

Rosemary did not notice Scarlett’s efforts to find a common ground. She was lost in a lost world: Dunmore Landing before the War. “This was called ‘the hidden garden’ because of the way the tall hedges along the paths kept you from seeing it until all of a sudden you were in it. When I was little I’d hide in here whenever bath time was coming. The servants were wonderful to me—they’d thrash around the hedges shouting back and forth about how they knew they’d never find me. I thought I’d been so clever. And when my Mammy stumbled through the gate, she’d always act surprised to see me . . . I loved her so much.”

“I had a Mammy, too. She—”

Rosemary was already moving on. “Down this way is the reflecting pool. There were black swans and white ones. Rhett says maybe they’ll come back once the reeds are cut out and all that filthy algae cleaned up. See that clump of bushes? It’s really an island, purpose built for the swans to nest on. It was all grass, of course, clipped when it wasn’t nesting season. And there was a miniature Greek temple of white marble. Maybe the pieces are somewhere in the tangle. A lot of people are afraid of swans. They can do terrible injury with their beaks and wings. But ours let me swim with them once the cygnets were out of the nest. Mama used to read me The Ugly Duckling sitting on a bench by the pool. When I learned my letters, I read it to the swans . . .

“This path goes to the rose garden. In May you could smell them for miles on the river before you ever got to the Landing. Inside the house, on rainy days with the windows closed, the sweetness from all the big arrangements of roses made me feel sick as a dog . . .

“Down there by the river was the big oak with the treehouse in it. Rhett built it when he was a boy, then Ross had it. I’d climb up with a book and some jam biscuits and stay for hours and hours. It was much better than the playhouse Papa had the carpenters make for me. That was much too fancy, with rugs on the floors and furniture in my size and tea sets and dolls . . .

“Come this way. The cypress swamp is over there. Maybe there’ll be some alligators to watch. The weather’s been so warm they’re not likely to be in their winter dens.”

“No, thank you,” said Scarlett. “My legs are getting tired. I believe I’ll sit on that big stone for a while.”

The big stone turned out to be the base of a fallen, broken statue of a classically draped maiden. Scarlett could see the stained face in a thicket of brambles. She wasn’t really tired of walking, she was tired of Rosemary. And she certainly had no desire to see any alligators. She sat with the sun warm on her back and thought about what she’d seen. Dunmore Landing was beginning to come to life in her mind. It hadn’t been at all like Tara, she realized. Life here had been lived on a scale and in a style she knew nothing about. No wonder Charleston people had a reputation for thinking they were the be-all and end-all. They had lived like kings.

Despite the warmth of the sun she felt chilled. If Rhett worked day and night for the rest of his life, he’d never make this place what it once was, and that was exactly what he was determined to do. There wasn’t going to be much time in his life for her. And knowing about onions and yams wouldn’t be much help to her in sharing his life, either.

Rosemary returned, disappointed. She hadn’t seen a single ’gator. She talked nonstop while they were walking back to the house, giving their old names to gardens that were now only areas of rank weeds, boring Scarlett with complex descriptions of the varieties of rice once grown in fields that were now gone to marsh grass, reminiscing about her childhood. “I hated it when summer came!” she complained.

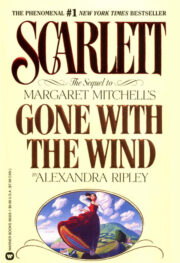

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.