People came pouring through the open doors, talking, laughing, pausing on the porch, reluctant to see the end of the evening. As they did every year, they said that this had been the best Saint Cecilia ever, the best orchestra, the best food, the best punch, the best time they had ever had.

The streetcar driver spoke to his horses. “I’ll get you to your stable, boys, don’t you fret.” He pulled the handle near his head and the brightly polished bell beside the blue light clanged its summons.

“Good night, good night,” cried obedient riders to the people on the porch and first one couple, then three, then a laughing avalanche of young people ran along the white canvas path. Their elders smiled and made comments about the tirelessness of youth. They moved at a slower, more dignified pace. In some cases their dignity failed to hide a certain unsteadiness of the legs.

Scarlett plucked Rhett’s sleeve. “Oh, do let’s ride the car, Rhett. The air feels so good and the carriage will be stuffy.”

“There’s a long walk after we get off.”

“I don’t care. I’d love to walk some.”

He took a deep breath of the fresh night air. “I would, too,” he said. “I’ll tell Mama. Go on to the car and save us a place.”

They hadn’t far to ride. The streetcar turned east on Broad Street, only a block away, then moved grandly through the silent city to the end of Broad in front of the Post Office building. It was a merry, noisy continuation of the party. Almost everyone on the crowded car joined in the song started by three laughing men when the car teetered around the corner. “Oh, the Rock Island Line, its a fine line! The Rock Island Line, it is the road to ride . . .”

Musically the performance left much to be desired but the singers neither knew nor cared. Scarlett and Rhett sang as loudly as the rest. When they stepped down from the car she continued to join in every time the chorus was repeated. “Get your ticket at the station for the Rock Island Line.” Rhett and three other volunteers helped the driver unharness the horses, lead them to the opposite end of the car, and rehitch them for the journey back along Broad then up Meeting to the terminal. They returned waves and cries of “good night” as the car moved away, taking the singers with it.

“Do you suppose they know any other song?” Scarlett asked.

Rhett laughed. “They don’t even know that one, and to tell the truth neither do I. It didn’t seem to make much difference.”

Scarlett giggled. Then she put her hand over her mouth. Her giggle had sounded very loud now that “The Rock Island Line” was faint in the distance. She watched the lighted car become smaller, then stop, then start, then disappear as it turned the corner. It was very quiet, and very dark outside the pool of light thrown by the street lamp in front of the Post Office. A breath of wind played with the fringe on her shawl. The air was balmy and soft. “It’s real warm,” she whispered to Rhett.

He murmured a wordless affirmative and took out his pocket watch, held it in the lamplight. “Listen,” he said quietly.

Scarlett listened. Everything was still. She held her breath to listen harder.

“Now!” said Rhett. Saint Michael’s bells chimed once, twice. The notes hung in the warm night for a long time. “Half past,” Rhett said with approval. He replaced the watch in its pocket.

Both of them had taken quite a bit of punch. They were in the condition known as “high flown,” where everything was somewhat magnified in effect. The darkness was blacker, the air warmer, the silence deeper, the memory of the pleasant evening even more enjoyable than the ball itself. Each felt a quietly glowing inner well-being. Scarlett yawned happily and tucked a hand into Rhett’s elbow. Without a word they began to walk into the darkness toward home. Their footsteps were loud on the brick sidewalk, bounced back from the buildings. Scarlett looked uneasily from side to side, and over her shoulder at the looming Post Office. She couldn’t recognize anything. It’s so quiet, she thought, like we were the only people on the face of the earth.

Rhett’s tall form was a part of the darkness, his white shirt front covered by his black evening cape. Scarlett tightened her hold on his arm, above the crook of the elbow. It was firm and strong, the powerful arm of a powerful man. She moved a little closer to his side. She could feel the warmth of his body, sense the bulk and strength of it.

“Wasn’t that a wonderful party?” she said too loudly. Her voice echoed, sounding strange to her ears. “I thought I’d laugh out loud at old look-down-your-nose Hannah. My grief, when she got a taste of how Southerners treat folks, her head was so turned I expected her to start walking backwards to see where she was going.”

Rhett chuckled. “Poor Hannah,” he said, “she may never again in her life feel so delightfully attractive and witty. Townsend’s no fool. He told me he wants to move back to the South. This visit will probably make Hannah agree. There’s a foot of snow on the ground in Philadelphia.” Scarlett laughed softly into the balmy darkness, then smiled with warm contentment. When she and Rhett walked through the light of the next streetlamp, she saw that he was smiling, too. There was no further need to talk. It was enough that they were both feeling good, both smiling, walking together, in no hurry to be any place else.

Their route took them past the docks. The sidewalk abutted a long row of ships chandlers, narrow buildings with tightly shuttered shops on street level and the darkened windows of living quarters above. Many of the windows were open to the almost-summery warmth of the night. A dog barked half-heartedly at the sound of their steps. Rhett commanded it to be quiet, his own voice muted. The dog whimpered once, then was still.

They walked forward, past widely spaced street lamps. Rhett adjusted his long stride automatically to match Scarlett’s shorter one, and the sound of heels on brick became a single clack clack clack clack—testimony of the comfortable unity of the moment.

One street lamp had gone out. In the patch of greater darkness Scarlett noticed for the first time that the sky seemed very near, its spangling of stars brighter than she could remember them ever before. One star looked almost close enough to touch. “Rhett, look at the sky,” she said softly. “The stars look so close.” He stopped walking, put his hand over hers to signal her to stop, too. “It’s because of the sea,” he said, the sound of his voice low and warm. “We’re past the warehouses now, and there’s only water. Listen and you can hear it breathing.” They stood very still.

Scarlett strained to hear. The rhythmic slap slap of the moving water against the invisible pilings of the seawall became audible. Gradually it seemed to get louder, until she was amazed she hadn’t been hearing it all the time. Then another sound merged with the cadence of the tidal river. It was music, a thin high slow procession of notes. The purity of them made her eyes fill with unexpected tears.

“Do you hear it?” she asked fearfully. Was she imagining things?

“Yes. It’s a homesick sailor on the ship anchored out there. The tune is ‘Across the Wide Missouri.’ They make those flute-like whistles themselves. Some of them have a real gift for playing. He must have the watch. See, there’s a lantern in the rigging, that’s where the ship is. The lantern’s supposed to warn any other ship traffic that she’s anchored there, but you always have a man on watch, too, to look for anything approaching. Maybe two in busy lanes like this river. There are always small boats, people who know the river moving at night when no one can see them.”

“Why would they do that?”

“A thousand reasons, all of them either dishonest or noble, depending on who’s telling the story.” Rhett sounded as if he were talking to himself more than to Scarlett.

She looked at him but it was too dark to see his face. She looked back at the ship’s lantern that she had mistaken for a star and listened to the tide and the music of the yearning, anonymous sailor. Saint Michael’s bells rang the three-quarter hour.

Scarlett tasted salt on her lips. “Do you miss the blockade running, Rhett?”

He laughed once. “Let’s just say I’d like to be ten years younger.” He laughed again, lightly mocking, amused at himself. “I play with sailboats under the guise of being kind to confused young men. It gives me the pleasure of being on the water and feeling the wind blowing free. There’s nothing like it for making a man feel like a god.” He moved forward, pulling Scarlett into motion. Their pace was slightly faster, but still in step.

Scarlett tasted the air and thought of the wing-like sails of the small boats that skimmed the harbor, almost flying. “I want to do that,” she said, “I want to go sailing more than anything in the whole world. Oh, Rhett, will you take me? It’s as warm as summer, you don’t absolutely have to go back to the Landing tomorrow. Say you will, please, Rhett.”

He thought for a moment. Very soon she’d be out of his life forever.

“Why not? It’s a shame to waste the weather,” he said.

Scarlett pulled at his arm. “Come on, let’s hurry. It’s late, and I want to get an early start.”

Rhett held back. “I won’t be able to take you sailing if you’ve got a broken neck, Scarlett. Watch your step. We’ve only got a few more blocks to go.”

She fell into step with him again, smiling to herself. It was wonderful to have something to look forward to.

Just before they reached the house Rhett stopped, stopping her. “Wait a second.” His head was lifted up, listening.

Scarlett wondered what he was hearing. Oh, for heaven’s sake, it was just Saint Michael’s clock again. The chimes ended and the deep reverberating single bell tolled three times. Distant but distinct in the warm darkness the voice of the watchman in the steeple called to the sleeping old city.

“Three . . . o’clock . . . and all’s well!”

31

Rhett looked at the costume Scarlett had assembled with such care, and one eyebrow skidded upward while his mouth twitched downward at the corner.

“Well, I didn’t want to get sunburned again,” she said defensively. She was wearing a wide-brimmed straw hat that Mrs. Butler kept near the garden door for protection from the sun when she went out to cut flowers. She had wrapped yards of bright blue tulle around the crown of the hat and tied the ends under her chin in a bow that she thought very becoming. She had her favorite parasol with her, a saucy pale blue flowered silk pagoda-shape with a dark blue tasselled fringe. It kept her dull, proper brown twill walking-out costume from being so boring, she thought.

What made Rhett think he could criticize anybody else, anyhow? He looked like a field hand, she thought, in those beat-up old breeches and that plain shirt without so much as a collar, never mind a proper cravat and coat. Scarlett set her jaw. “You said nine o’clock, Rhett, and that’s what it is. Shall we go?”

Rhett made a sweeping bow, then picked up a battered canvas bag and slung it over his shoulders. “We shall go,” he said. There was something suspicious about his voice. He’s up to something, Scarlett thought, but I’m not about to let him get away with it.

She’d had no idea that the boat was so small. Or that it would be at the bottom of a long ladder that looked so slimy wet. She looked accusingly at Rhett.

“Nearly low tide,” he said. “That’s why we had to get here by nine-thirty. After the tide turns at ten, we would have a hard time getting into the harbor. Of course it will be a help bringing us back up the river to dock. . . . If you’re quite certain that you want to go.”

“Quite, thank you.” Scarlett put her white-gloved hand on one projecting rail of the ladder and started to turn around.

“Wait!” said Rhett. She looked up at him with a stonily determined face. “I’m not willing to let you break your neck to spare me the trouble of taking you out for an hour. That ladder’s very slippery. I’ll go down one rung before you to make sure you don’t lose your footing in those foolish city boots. Stand by while I get ready.” He opened the drawstring of the canvas bag and took out a pair of canvas shoes with rubber soles. Scarlett watched in silent stubbornness. Rhett took his time, removing his hoots, putting on the shoes, placing the boots in the bag, tightening the drawstring, making an intricate-looking knot in it.

He looked at her with a sudden smile that took her breath away. “Stay right there, Scarlett, a wise man knows when he’s beaten. I’ll stow this gear and come back for you.” In a flash he hoisted the bag on his shoulder and was halfway down the ladder before Scarlett understood what he was talking about.

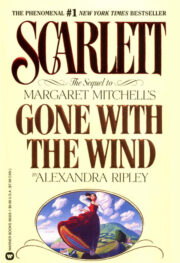

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.