“You skinnied down and up that thing like greased lightning,” she said with honest admiration when Rhett was beside her again.

“Or a monkey,” he corrected. “Come on, my dear, time and tide wait for no man, not even a woman.”

Scarlett was no stranger to ladders, and she had a good head for heights. As a child she had climbed trees to their topmost swaying branches and scampered up into the hayloft of the barn as if its narrow ladder were a broad flight of stairs. But she was grateful for Rhett’s steadying arm around her waist on the algae-coated rungs, and very glad to reach the relative stability of the small boat.

She sat quietly on the board seat in the stern while Rhett efficiently attached the sails to the mast and tested the lines. The white canvas lay in heaps, on the covered bow and inside the open cockpit. “Ready?” he said.

“Oh, yes!”

“Then let’s cast off.” He freed the lines that hugged the tiny sloop to the dock and pushed away from the barnacle-crusted pier support with a paddle. The fast-running ebb tide grabbed the little boat at once and pulled it into the river. “Sit where you are and keep your head down on your knees,” Rhett ordered. He hoisted the jib, cleared halyard and sheet, and the narrow sail filled with wind, luffing gently.

“Now.” Rhett sat on the seat beside Scarlett and hooked his elbow over the tiller between them. With his two hands he began to haul up the mainsail. There was a great noise of creaking and rattling. Scarlett stole a sideways look without lifting her head. Rhett’s eyes were squinting against the sun and he was frowning in concentration. But he looked happy, as happy as she had ever seen him.

The mainsail bellied out with a booming snap and Rhett laughed. “Good girl!” he said. Scarlett knew that he wasn’t talking to her.

“Are you ready to go in?”

“Oh, no, Rhett! Not ever.” Scarlett was in a transport of delight with the wind and the sea, unconscious of the spray spotting her clothes, the water running across her boots, the total ruin of her gloves and Miss Eleanor’s hat, the loss of her parasol. She had no thoughts, only sensation. The sloop was a mere sixteen feet long, its hull sometimes barely inches above the sea. It rode waves and current like an eager young animal, climbing to the crests, then swooping into the troughs with a dashing plunge that left Scarlett’s stomach somewhere high up near her throat and threw a fan of salty droplets into her face and open, exultant mouth. She was part of it—she was the wind and the water and the salt and the sun.

Rhett looked at her rapt expression, smiled at the sodden foolish tulle bow under her chin. “Duck,” he ordered, and put the tiller over for a short tack into the wind. They’d stay out a bit longer. “Would you like to take the tiller?” he offered. “I’ll teach you to sail her.”

Scarlett shook her head. She had no desire to control, she was happy simply to be.

Rhett knew how remarkable it was for Scarlett to turn down an opportunity to rule, understood the depth of her response to the joyous freedom of sail on sea. He had felt the same rapture often in his youth. Even now he had brief moments of it from time to time, moments that sent him back onto the water again and again in search of more.

“Duck,” he said again. And put the little sloop into a long reach. The suddenly increased speed brought water foaming onto the deep-slanted edge of the hull. Scarlett let out a cry of delight. Overhead the cry was repeated by a soaring sea gull, bright white against the high wide cloudless blue sky. Rhett looked up and grinned. The sun was warm on his back, the wind sharp and salty on his face. It was a good day to be alive. He lashed the tiller and moved forward in a stoop to get the canvas bag. The sweaters he pulled out of it were stretched and misshapen with age, stiff with dried brine. They were made of thick wool in a blue so dark that it looked almost black. Rhett crab-walked back to the stern and sat down on the raked outer edge of the cockpit. The cant of the hull dropped with his weight, and the lively little boat hissed through the water on an almost even keel.

“Put this on, Scarlett.” He held one of the sweaters out to her.

“I don’t need it. It’s like summertime today.”

“The air’s warm enough, but not the water. It’s February whether it seems like summer or not. The spray will chill you without your knowing it. Put on the sweater.”

Scarlett made a face, but she took the sweater from him. “You'll have to hold my hat.”

“I’ll hold your hat.” Rhett pulled the second, grimier sweater over his head. Then he helped Scarlett. Her head emerged, and the wind assaulted her dishevelled hair, pulling it free from dislodged combs and hairpins and tossing it in long, dark leaping streamers. She shrieked and grabbed wildly at it.

“Now look what you've done!” she shouted. The wind whipped a thick strand of hair into her open mouth, making her sputter and blow. When she pulled the hair free it tore out of her grasp and flew into snarled witches’ locks with the rest. “Give me my hat quick before I’m bald-headed,” she said. “My grief, I’m a mess.”

She had never in her life looked so beautiful. Her face was alight with joy, rosy from windburn, glowing amid the wild dark cloud of hair. She tied the ridiculous hat firmly on her head, tucked her subdued tangled hair into the back of the sweater. “I don’t suppose you have anything to eat in that bag of yours, do you?” she asked hopefully.

“Only sailors’ rations,” said Rhett, “hardtack and rum.”

“That sounds delicious. I’ve never tasted either one.”

“It’s not much past eleven, Scarlett. We’ll be home for dinner. Restrain yourself.”

“Can’t we stay out all day? I’m having such a good time.”

“Another hour; I have a meeting with my lawyers this afternoon.”

“Bother your lawyers,” said Scarlett, but under her breath. She refused to get angry and spoil her pleasure. She looked at the sunspangled water and the white curls of foam on each side of the bow, then flung out her arms and arched her back in a luxurious cat-like stretch. The sleeves of the sweater were so long that they extended past her hands, flapping in the wind.

“Careful, my pet,” Rhett laughed, “you might blow away.” He freed the tiller, preparing to come about, looking automatically for any other vessels that might be in his proposed path.

“Look, Scarlett,” he said urgently, “quick. Out there to starboard—to your right. I’ll bet you’ve never seen that before.”

Scarlett’s eyes scanned the marshy shore in the near distance. Then—halfway between boat and shore—a gleaming gray shape curved above the water for a moment before disappearing beneath it.

“A shark!” she exclaimed. “No, two—three sharks. They’re coming right at us, Rhett. Do they want to eat us?”

“My dear imbecilic child, those are dolphins, not sharks. They must be heading for the ocean. Hold tight and duck. I’m going to bring her around tight. Maybe we can travel with them. It’s the most charming thing in the world to be in the middle of a school of them. They love to play.”

“Play? Fish? You must think I’m mighty gullible, Rhett.” She bent under the swinging boom.

“They aren’t fish. Just watch. You’ll see.”

There were seven dolphins in the pod. By the time Rhett maneuvered the sloop onto the course the sleek mammals were following, the dolphins were far ahead. Rhett stood and shaded his eyes against the sun. “Damn!” he said. Then, immediately in front of the sloop, a dolphin leapt from the water, bowed its back, and dived with a splash back into the water.

Scarlett pounded on Rhett’s thigh with a sweater-mittened fist. “Did you see that?”

Rhett dropped onto the seat. “I saw it. He came to tell us to get a move on. The others are probably waiting for us. Look!” Two dolphins had broken water ahead. Their graceful leaps made Scarlett clap her hands. She pushed the sweater sleeves up her arms and clapped again, this time successfully. Two yards to her right the first dolphin surfaced, cleared his blow hole with a spurt of spume, then lazily rocked back down into the water.

“Oh, Rhett, I never saw anything so darling. It was smiling at us!”

Rhett was smiling, too. “I always think they’re smiling, and I always smile back. I love dolphins, always have.”

The dolphins treated Rhett and Scarlett to what could only be called a game. They swam alongside, under, across the bow, sometimes singly, sometimes in twos or threes. Diving and surfacing, blowing, rolling, leaping, looking from eyes that seemed human, seemed to be laughing above the engaging smile-like mouth at the clumsy, boat-bound man and woman.

“There!” Rhett pointed when one burst from the surface in a leap, and “There!” Scarlett yelled when another leapt in the opposite direction. “There!” and “There!” and “There!” whenever the dolphins broke water. It was a surprise each time, always in a spot that was different from the places where Scarlett and Rhett were looking.

“They’re dancing,” Scarlett insisted.

“Frolicking,” Rhett suggested.

“Showing off,” they agreed. The show was enchanting.

Because of it Rhett was careless. He didn’t see the dark patch of cloud that was spreading across the horizon behind them. His first warning was when the steady fresh wind suddenly dropped. The taut billowing sails went limp, and the dolphins nosed abruptly down into the water and disappeared. He looked then—too late—over his shoulder and saw the squall racing over the water and the sky.

“Get down into the belly of the boat, Scarlett,” he said quietly, “and hold on. We’re about to have a storm. Don’t be frightened, I’ve sailed through much worse.”

She looked behind and her eyes widened. How could it be so sunny and blue in front of them and so black back there? Without a word she slid down and found a handhold beneath the seat where she and Rhett had been sitting.

He was making rapid adjustments to the rigging. “We’ll have to run before it,” he said, then he grinned. “You’ll get wet, but it will be a hell of a ride.” At that moment the squall hit. Day turned to liquid near-night as the clouds blackened the sky and loosed sheets of rain on them. Scarlett opened her mouth to cry out, and it was immediately filled with water. “We’ll have to run before it,” he said, then he grinned. “You’ll get wet, but it will be a hell of a ride.” At that moment the squall hit. Day turned to liquid near-night as the clouds blackened the sky and loosed sheets of rain on them. Scarlett opened her mouth to cry out, and it was immediately filled with water.

My God, I’m drowning, she thought. She bent over and spat and coughed until her mouth and throat were clear. She tried to lift her head, to see what was happening, to ask Rhett what was that terrible noise. But her giddy battered hat was collapsed onto her face, and she couldn’t see anything. I’ve got to get rid of it or I’ll suffocate. She tore at the tulle bow under her chin with her free hand. Her other hand was desperately gripping the metal handle she had found. The boat was pitching and yawing, creaking as if it was coming apart. She could feel the sloop racing down, down—it must be almost standing on its nose, it’s going to go straight through the water, right to the bottom of the sea. Oh, sweet Mother of God, I don’t want to die!

With a shudder the sloop stopped its plunge. Scarlett pulled the wet tulle roughly over her chin, over her face, and she was free of the smothering folds of wet straw. She could see!

She looked at the water, then up, at water, then up . . . up . . . up. There was a wall of water higher than the tip of the mast, ready to fall and smash the frail wooden shell to bits. Scarlett tried to scream, but her throat was paralyzed by fear. The sloop was shaking and groaning; it rode with a sickening slide up the side of the wall, then hung on the top, shuddering, for an endless terrifying moment.

Scarlett’s eyes were narrowed against the rain pouring down on her head with terrible pounding blows, streaming down over her face. On all sides there were angry, surging, foam-streaked mountainous waves with curling breaking white tops streaming fans of spume into the furious wind and rain. “Rhett,” she tried to shout. Oh God, where was Rhett? She turned her head from side to side, trying to see through the rain. Then, just as the sloop dove furiously down the other side of the wave, she found him.

God damn his soul! He was kneeling, his back and shoulders straight, his head and chin high, and he was laughing into the wind and the rain and the waves. His left hand gripped the tiller with corded strength, and his right hand was outstretched, holding on to the line that was wrapped around his elbow and forearm and wrist, the sheet that led to the fearful pull of the huge wind-filled mainsail. He’s loving this! The fight with the wind, the death danger. He loves it.

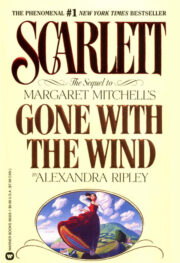

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.