I hate him!

Scarlett looked up at the towering threat of the next wave and for a wild, despairing instant she waited for it to topple, to trap, to destroy her. Then she told herself that she had nothing to fear. Rhett could manage anything, even the ocean itself. She lifted her head, as his was lifted, and gave herself over to the wild perilous excitement.

Scarlett did not know about the chaotic power of the wind. As the little sloop rode up the side of the thirty-foot wave, the wind stopped. It was only for a few seconds, a freak of the center of the squall, but the mainsail flattened, and the boat slewed to broadside, carried erratically by water current only in a perilous climb. Scarlett was aware that Rhett was rapidly freeing his arm from the encircling slack line, that he was doing something different with the swinging tiller, but she had no hint that anything was wrong until the crest of the wave was nearly under the keel and Rhett shouted, “Jibe! Jibe,” and threw his body painfully over hers.

She heard a rattling, creaking noise close to her head and sensed the slow then faster then rushing swing of the heavy boom above. Everything happened very fast, yet it seemed to be terribly, unnaturally slow, as though the whole world were stopping. She looked without understanding at Rhett’s face so near to hers, and then it was gone and he was on his knees again doing something, she didn’t know what, except that heavy loops of thick rope were falling on her.

She didn’t see the crosswind ruffle, then suddenly fill, the wet canvas of the mainsail and propel it to the opposite side of the wayless sloop with an ever-mounting force so mightly that there was a crack like the sound of lightning striking and the thick mast broke and was carried into the sea by the momentum and weight of the sail. The hull of the boat bucked, then lifted to starboard and rolled slowly, following the pull of the fouled rigging, until it was upside down. Capsized in the cold storm-torn sea.

She’d never known such cold could exist. Cold rain pelting her, colder waters surrounding her, pulling at her. Her whole body must be frozen. Her teeth were chattering uncontrollably, making such a noise in her head that she couldn’t think, couldn’t understand what was happening, except that she must be paralyzed, because she couldn’t move. And yet she was moving, in sickening swings and surging lifts and terrible, terrible falling, falling.

I’m dying. Oh God, don’t let me die! I want to live.

“Scarlett!” The sound of her name was louder than the clacking of her teeth and it penetrated to her consciousness.

“Scarlett!” She knew that voice, it was Rhett’s voice. And that was Rhett’s arm around her, holding her. But where was he? She couldn’t see anything through the water that kept hitting her face, glazing and stinging her eyes.

She opened her mouth to answer and at once it was filled with water. Scarlett craned her head up as hard as she could and blew the water from her mouth. If only her teeth would be still!

“Rhett,” she tried to say.

“Thank God.” His voice was very close. Behind her. She was beginning to make some kind of sense of things.

“Rhett,” she said again.

“Now listen carefully, my darling, listen harder than you’ve ever listened in your life. We’ve got one chance, and we’re going to take it. The sloop is right here; I’m holding on to the rudder. We’ve got to get under it and use it for protection. That means we’ve got to go under the water and come up under the hull of the boat. Do you understand?”

Everything in her cried out, No! If she went under the water she’d drown. It was pulling her already, dragging at her. If she went under, she’d never come up! Panic seized her. She couldn’t breathe. She wanted to hold on to Rhett, and she wanted to scream and scream and scream—

Stop it. The words were clear. And the voice was her own. You’ve got to live through this, and you’ll never do it if you act like a gibbering idiot.

“Wh-wh-what sh-should I d-d-d-do?” Damn this chattering.

“I’m going to count. At ‘three’ take a deep breath and close your eyes. I’ve got you. I’ll get us there. You’ll be all right. Are you ready?” He didn’t wait for her to answer, but began at once to shout “One . . . two . . .” Scarlett inhaled in jerky spurts. Then she was pulled down, down, and water filled her nose and ears and eyes and consciousness. In seconds, it was over. She gulped air gratefully.

“I’ve been holding your arms, Scarlett, so you wouldn’t grab me and drown us both.” Rhett moved his grip to her waist. The freedom felt wonderful. If only her hands weren’t so cold. She began to rub them together.

“That’s the way,” said Rhett. “Keep your circulation going. But not quite yet. Take hold of this cleat. I must leave you for a few minutes. Don’t panic. It won’t be long. I’m going to duck back up and cut away the fouled lines and the mast before they pull the boat under. I’m going to cut the laces on your boots, too, Scarlett. Don’t kick when you feel something grab your foot. It’ll be me. Those heavy skirts and petticoats will have to go, too. Just hold on tight. I won’t be long.”

It seemed like forever.

Scarlett used the time to assess her surroundings. Things weren’t too bad—if she could ignore the cold. The overturned sloop made a roof over her head, so that the rain was not hitting her. For some reason the water was calmer, too. She couldn’t see it; the inside of the hull was totally dark; but she knew it was so. Although the boat was rising and falling with the surge of the waves in the same dizzying rhythm, the surface of the sheltered water was almost flat, no choppy little waves to break against her face.

She felt Rhett’s touch on her left foot. Good! I’m not really paralyzed. Scarlett took a deep breath for the first time since the storm hit. How strange her feet felt. She’d had no idea how heavy and constricting boots were. Oh! The hand at her waist was strangefeeling. She could sense the sawing motion of the knife. Then suddenly a tremendous weight slid down her legs and her shoulders bobbed up out of the water. She cried out in surprise. The sound of her cry reverberated in the hollow space beneath the wooden hull. It was so loud that she almost lost her handhold from the shock of it.

Then Rhett burst through the water. He was very close to her. “How do you feel?” he asked. It sounded as if he was shouting.

“Shhh,” said Scarlett. “Not so loud.”

“How do you feel?” he asked quietly.

“Frozen nearly to death, if you really want to know.”

“The water’s cold, but not that cold. If we were in the North Atlantic—”

“Rhett Butler, if you tell me one of your blockade-running adventure stories, I’ll—I’ll drown you!”

His laughter filled the air around them and it seemed somehow to make it warmer. But Scarlett was still furious. “How you can laugh at a time like this is beyond me. It’s not funny to be dangling in freezing water in the middle of a terrible storm.”

“When things are at their worst, Scarlett, the only thing to do is find something to laugh about. It keeps you sane . . . and it stops your teeth chattering from fear.”

She was too exasperated to speak. The worst of it was that he was right. The chattering had stopped when she stopped thinking that she was going to die.

“Now I’m going to cut the laces on your corset, Scarlett. You can’t breathe easily in that cage. Just hold still so I don’t cut your skin.” There was an embarrassing intimacy in the movement of his hands under the sweater, tearing open her basque and her shirtwaist. It had been years since he had last put his hands on her body.

“Now, breathe deep,” said Rhett when he pulled the cut corset and camisole away. “Women today never learn how to breathe. Fill your lungs all the way. I’m rigging a support for us with some line I cut. You’ll be able to turn loose that cleat when I’m done and massage your hands and arms. Keep breathing. It’ll warm up your blood.”

Scarlett tried to do what Rhett said, but her arms felt terribly heavy when she lifted them. It was much easier just to let her body rest in the harness-like rope support under her arms and rise and fall, limp, with the rise and fall of the waves. She was feeling very sleepy . . . Why did Rhett have to keep talking so much? Why did he insist on fussing at her about rubbing her arms?

“Scarlett!” The sound was very loud. “Scarlett! You cannot go to sleep. You’ve got to keep moving. Kick your feet. Kick me if you want to, but move your legs.” Rhett began to rub her shoulders vigorously, then her upper arms; his touch was rough.

“Stop it. That hurts.” Her words were weak, like the mewing of a kitten. Scarlett closed her eyes, and the darkness became darker. She didn’t feel so cold any more, only very tired, and sleepy.

With no warning Rhett slapped her face so hard that her head jerked backwards and hit the wooden hull with a crash that echoed in the enclosed space. Scarlett came full awake, shocked and angry.

“How dare you! I’ll pay you back for that when we get out of here, Rhett Butler, just see if I don’t!”

“That’s better,” said Rhett. He continued to rub her arms roughly, though Scarlett was trying to push his hands away. “Keep talking, I’ll do the massage. Give me your hands so I can rub them.”

“I certainly will not! I’ll keep my hands to myself and I’ll thank you to do the same. You’re rubbing my flesh right off my bones.”

“Better my rubbing than crabs eating it,” said Rhett harshly. “Listen to me. If you let yourself give in to the cold, Scarlett, you’ll die. I know you want to sleep but that’s the sleep of death. And, by God, if I have to beat you black and blue, I will not allow you to die. You stay awake, and breathe, and keep moving. Talk; keep talking; I don’t give a damn what you say, just let me hear your cantankerous fishwife tones so I’ll know you’re alive.”

Scarlett was aware of the paralyzing cold again as Rhett rubbed life back into her flesh. “Are we going to get out of this?” she asked without emotion. She tried to move her legs.

“Of course we are.”

“How?”

“The current is carrying us ashore; it’s an incoming tide. It’ll take us back where we came from.”

Scarlett nodded in the darkness. She remembered all the fuss about leaving before the tide turned. Nothing in Rhett’s voice revealed his knowledge that the power of gale-force winds would make all normal tidal activity meaningless. The storm might be carrying them through the mouth of the harbor into the vast reaches of the Atlantic Ocean.

“How long before we get there?” Scarlett’s tone was querulous. Her legs felt like huge tree trunks. And Rhett was rubbing her shoulders raw.

“I don’t know,” he answered. “You’ll need all your courage, Scarlett.”

He sounds as solemn as a sermon! Rhett, who always makes fun of everything. Oh, my God! Scarlett willed her lifeless legs to move and forced terror away with iron determination. “I don’t need courage half as much as something to eat,” she said. “Why the devil didn’t you grab that dirty old bag of yours when we turned over?”

“It’s stowed under the bow. By God, Scarlett, your gluttony may be the saving of us. I’d forgotten all about it. Pray it’s still there.”

The rum spread life-restoring tentacles of warmth through her thighs, her legs, her feet, and Scarlett began to push them back and forth. The pain of returning circulation was intense, but she welcomed it. It meant she was alive, all of her. Why, rum just might be better than brandy, she thought after a second drink. It sure did warm a person up.

Too bad that Rhett insisted on rationing it, but she knew he was right. It would be too awful to run out of the warmth in the bottle before they were safe on land. In the meantime she was even able to join in Rhett’s tribute to their prize. “ ‘Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle of rum!’ ” she sang with him when he finished each verse of the sea chanty.

And afterwards Scarlett thought of “Little brown jug, how I love thee.”

Their voices echoed so loudly inside the hull that it was possible to pretend that they weren’t growing weaker as the cold gripped their bodies. Rhett put his arms around Scarlett and held her close to his body to share its warmth. And they sang all the favorites they could remember, while the sips of rum came closer together with less and less effect.

“How about ‘The Yellow Rose of Texas’?” Rhett suggested.

“We sang that twice already. Sing that song Pa loved so much, Rhett. I remember the two of you staggering down the street together in Atlanta bellowing like stuck pigs.”

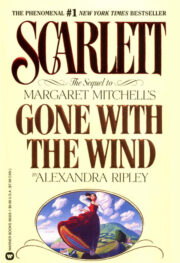

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.