“Wash your face,” said Scarlett impatiently, thereby revealing her ignorance and the recent date of her return to religion. She dropped her napkin on the table. “I’ve got to be off,” she said briskly. “I . . . I’m going to visit my O’Hara uncles and aunts.” She didn’t want anyone to know that she was trying to buy the convent’s share of Tara. Especially not her aunts, they gossiped too much. Why, they might even write to Suellen. She smiled sweetly. “What time do we leave in the morning for Mass?” She’d be sure to mention it to the Mother Superior. No need to let on that she’d forgotten all about Ash Wednesday.

What a bother it was that she’d left her rosary in Charleston. Oh, well, she could buy a new one at her O’Hara uncles’ store. If she remembered correctly, they had everything in there from bonnets to plows.

“Miss Scarlett, when are we going home to Atlanta? I don’t feel comfortable with the folks in your Grandpa’s kitchen. They is all so old. And my shoes is just about wore out from all this walking. When are we going home where you got all the fine carriages?”

“Stop that everlasting complaining, Pansy. We’ll go when I say go and where I say go.” Scarlett’s response had no real heat in it; she was trying to remember where her uncles’ store was, and having no luck. I must be catching old folks’ forgetfulness. Pansy’s right about that part. Everybody I know in Savannah is old. Grandfather, Aunt Eulalie, Aunt Pauline, all their friends. And Pa’s brothers are the oldest of all. I’ll just say hello and let them give me a nasty dry old man’s kiss on the cheek and buy my rosary and leave. There’s no real call to see their wives. If they cared about seeing me, they would have done something about keeping up all these years. Why, for all they know I could be dead and buried and not so much as a condolence note to my husband and children. A mighty tacky way to treat a blood relative, I call it. Maybe I’ll just forget about going to see any of them at all. They don’t deserve any visits from me after the way they neglected me, she thought, ignoring the letters from Savannah that she’d never answered, until finally they stopped coming.

She was ready to consign her father’s brothers and their wives permanently to oblivion in the recesses of her mind now. She was fixed on two things, getting control of Tara and getting the upper hand with Rhett. Never mind that the two were contradictory goals, she’d find a way to have both. And they demanded all the thinking she had time for. I’m not going to go trailing around looking for that musty old store, Scarlett decided. I’ve got to track down the Mother Superior and the Bishop. Oh, I do wish I hadn’t left those beads in Charleston. She looked quickly along the storefronts on the other side of Broughton Street, Savannah’s place to shop. Surely there must be a jeweler somewhere close by.

The bold gilt letters that spelled out O’HARA stretched across the wall above five gleaming windows almost directly opposite. My, they’ve come up in the world since I was here last, Scarlett thought. That doesn’t look musty at all. “Come on,” she said to Pansy, and she plunged into the tangled traffic of wagons, buggies, and pushcarts that filled the busy street.

The O’Hara store smelled of fresh paint, not long-settled dust. A green tarlatan banner draped across the front of the counter in the rear gave the reason in gold letters: GRAND OPENING. Scarlett looked around enviously. The store was more than twice the size of her store in Atlanta, and she could see that the stock was fresher and more varied. Neatly labelled boxes and bolts of bright fabrics filled shelves to the ceiling; barrels of meals and flours were lined up along the floor, not far from the big potbellied stove in the center; and huge glass jars of candy stood temptingly on the tall counter. Her uncles were moving up in the world for sure. The store she’d visited in 1861 wasn’t in the central, fashionable part of Broughton Street, and it was dark, cluttered, even more so than hers in Atlanta. It would be interesting to find out what this handsome expansion had cost her uncles. She might just consider a few of their ideas for her own business.

She walked quickly to the counter. “I’d like to see Mr. O’Hara, if you please,” she said to the tall, aproned man who was measuring out some lamp oil into a customer’s glass jug.

“In a moment, if you’ll be so kind as to wait, ma’am,” the man said without looking up. His voice had just a hint of brogue in it.

That makes sense, thought Scarlett. Hire Irish for a shop run by Irishmen. She looked at the labels on the shelved boxes in front of her while the man wrapped the oil in brown paper and made change. Hmmm, she should be keeping gloves that way, too, by size not by color. You could see the colors quick enough when you opened the box, but it was a real bother to search for the right size in a box of gloves that were all of them black. Why hadn’t she thought of it before?

The man behind the counter had to speak again before Scarlett heard him. “I’m Mr. O’Hara,” he repeated. “How might I be of service to you?”

Oh, no, this wasn’t the uncles’ store after all! They must still be where they’d always been. Scarlett explained hurriedly that she’d made a mistake. She was looking for an elderly Mr. O’Hara, Mr. Andrew or Mr. James. “Can you direct me to their store?”

“But this is their store. I’m their nephew.”

“Oh . . . oh, my goodness. Then you must be my cousin. I’m Katie Scarlett, Gerald’s daughter. From Atlanta.”

Scarlett held out both her hands. A cousin! A big, strong, not-an-old-man cousin of her own. She felt as if she’d just been given a surprise present.

“Jamie, that’s me,” said her cousin with a laugh, taking her hands in his. “Jamie O’Hara at your service, Scarlett O’Hara. And what a gift you are to a weary businessman, to be sure. Pretty as a sunrise, and dropping from out of the blue like a falling star. Tell me now, how do you come to be here for the grand opening of the new store? Come let me get you a chair.”

Scarlett forgot all about the rosary she’d meant to buy. She forgot about the Mother Superior, too. And about Pansy, who settled herself on a low stool in a corner and went to sleep at once with her head resting on a neat pile of horse blankets.

Jamie O’Hara mumbled something under his breath when he returned from the back room with a chair for Scarlett. There were four customers waiting to be served. In the next half hour more and more came in, so that there was no chance for him to say a word to Scarlett. He looked at her from time to time with apology in his eyes, but she smiled and shook her head. There was no need to apologize. She was pleased just to be there, in a warm, well-run store that was doing a good business, with a new-found cousin whose competence and skillful treatment of his customers was a delight to observe.

At last there was a brief moment when the only customers were a mother and her three daughters who were looking through four boxes of laces. “I’ll talk like a rushing river, then, while I can,” said Jamie. “Uncle James will be longing to see you, Katie Scarlett. He’s an old gentleman, but still active enough. He’s here every day until dinnertime. You may not know it, but his wife died, God rest her soul, and Uncle Andrew’s wife as well. It took the heart out of Uncle Andrew, and he followed her within a month. May they all be resting in the arms of the angels. Uncle James lives in the house with me and my wife and children. It’s not far from here. Will you come to tea this afternoon and see them all? My boy Daniel will be back soon from making deliveries, and I’ll walk you to the house. We’re celebrating my daughter Patricia’s birthday today. All the family will be there.”

Scarlett said she’d love to go to tea. Then she took off her hat and cape and walked over to the ladies at the laces. There was more than one O’Hara who knew how to run a store. Besides, she was too excited to sit still. A birthday for her cousin’s daughter! Let’s see, she’ll be my first cousin once removed. Although Scarlett had grown up without the usual many-generation family network of the South, she was still a Southerner, and could name the exact relationship of cousins to the tenth remove. She had revelled in watching Jamie while he worked, because he was the living confirmation of everything Gerald O’Hara had told her. He had the dark curly hair and blue eyes of the O’Haras. And the wide mouth and short nose in the round, florid face. Most of all, he was a big man, tall and broad through the chest with strong thick legs like the trunks of trees that could withstand any storm. He was an impressive figure. “Your Pa is the runt of the litter,” Gerald had said without shame for himself but with enormous pride in his brothers. “Eight children my mother had, and all boys, and me the last and the only one not as big as a house.” Scarlett wondered which of the brothers was Jamie’s father. No matter, she’d find out at the tea. No, not tea, the birthday party! For her first cousin once removed.

35

Scarlett looked up at her cousin Jamie with carefully concealed curiosity. In the daylight of the open street the lines and pouches beneath his eyes weren’t blended away by shadows, the way they were inside the store. He was a middle-aged man, running to weight and softness. She’d assumed somehow that because he was her cousin he must be her age. When his son came in, she was shocked to be introduced to a grown man, not a boy who delivered packages. And a grown man with flaming red hair, to boot. It took some getting used to.

So did the sight of Jamie in daylight. He . . . he wasn’t a gentleman. Scarlett couldn’t specify how she knew that, but it was as clear as glass. There was something wrong with his clothes; his suit was dark blue, but not dark enough, and it fit him too closely through the chest and shoulders and too loosely everywhere else. Rhett’s clothing was, she knew, the result of superlative tailoring and, on his part, demanding perfectionism. She wouldn’t expect Jamie to dress like Rhett—she’d never known man who dressed like Rhett. But any still, he could do something—whatever it was that men did—so that he wouldn’t look so . . . so common. Gerald O’Hara had always looked like a gentleman, no matter how worn or rumpled his coat might be. It didn’t occur to Scarlett that her mother’s quiet authority and influence might have been at work on her father’s transformation to gentleman landowner. Scarlett only knew that she’d lost most of her joy in discovering the existence of her cousin. Well, I only have to have a cup of tea and a piece of cake, and then I can leave. She smiled brilliantly at Jamie. “I’m so thrilled to be meeting your family that I’ve taken leave of my senses, Jamie. I should have bought a present for your daughter’s birthday.”

“Aren’t I bringing her the best gift of all when I walk in with you on my arm, Katie Scarlett?”

He does have a twinkle in his eye, just like Pa, Scarlett told herself. And Pa’s teasing brogue. If only he wasn’t wearing a Derby hat! Nobody wears Derby hats.

“We’ll be walking past your grandfather’s house,” Jamie said, striking horror to Scarlett’s heart. What if her aunts saw them—suppose she had to introduce them? They always thought Mother married beneath her; Jamie would be all the proof they could ever want. What was he saying? She had to pay attention.

“. . . leave off your servant-girl there. She’d feel out-of-place with us. We don’t have any servants.”

No servants? Good Lord! Everybody has servants, everybody! What kind of place do they live in, a tenement? Scarlett squared her jaw. This is Pa’s own brother’s son, and Uncle James is Pa’s own brother. I won’t disgrace his memory by being too cowardly to take a cup of tea with them, even if there are rats running across the floor. “Pansy,” she said, “when we get to the house, you go on in. I’ll be back directly, you tell them . . . You will walk me home, won’t you, Jamie?” She was brave enough to face a rat running across her foot, but she wasn’t willing to ruin her reputation for all time by walking alone on the street. Ladies just didn’t do that.

To Scarlett’s relief they walked along the street behind her grandfather’s house, not by the square in front of it where her aunts liked to promenade under the trees for their “constitutionals.” Pansy went willingly through the gate into the garden, already yawning anticipation of going back to sleep. Scarlett tried not to look anxious. She’d heard Jerome complaining to her aunts about the deterioration of the neighborhood. Only a few blocks to the east the fine old homes had degenerated into ramshackle boardinghouses for the sailors who manned the ships in and out of Savannah’s busy port. And for the waves of immigrants who arrived on some of the ships. Most of them, according to the snobbish, elegant old black man, were unwashed Irish.

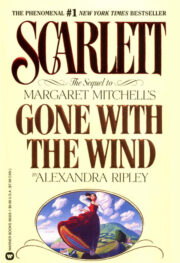

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.