Maureen smiled at her. “I believe there’s a readiness for a reel,” she said. She picked up the spoon by her plate, reached across Daniel and took his; then, placing their bowls back to back, she held the tips of the handles loosely together and tapped the spoons against her palm, against her wrist, her forearm, Daniel’s forehead. The rhythm of the beating was like playing the bones, but lighter, and the sheer silliness of making music with a pair of mismatched tablespoons was cause for delighted, spontaneous laughter from Scarlett. Without thinking about it, she began to pound on the table with her open hands, matching the beat of the spoons.

“It’s time we were going,” Jamie laughed. “I’ll get my fiddle.”

“We’ll bring the chairs,” said Mary Kate.

“Matt and Katie only have two,” Daniel explained to Scarlett. “They’re the newest O’Haras to come to Savannah.”

It didn’t matter at all that Matt and Katie O’Hara’s double parlors held almost no furniture. They had fireplaces for warmth, gaslit ceiling globes for light, and a broad, polished wood floor for dancing. The hours Scarlett passed in those bare rooms that Saturday were among the happiest she’d ever known.

Within the family the O’Haras shared love and happiness as freely and unconsciously as they shared the air they breathed. Scarlett felt within her the growth of something she had lost too long ago to remember. She became, like them, unaffected and spontaneous and open to carefree joy. She could shed the artifice and calculation that she’d learned to use in the battles for conquest and dominance that were part of being a belle in Southern society.

She had no need to charm or conquer; she was welcome as she was, one of the family. For the first time in her life she was willing to relinquish the spotlight to let someone else be the center of attention. The others were fascinating to her, primarily because they were her new-found family, but also because she’d never known anyone like them in her life.

Or almost never. Scarlett looked at Maureen, with Brian and Daniel making music behind her, Helen and Mary Kate clapping in time with the rhythm she was setting with the bones, and for a moment it was as if the vivid redheads were the youthful Tarletons come back to life. The twins, tall and handsome, the girls squirming with juvenile impatience to move on to the next adventure life held for them. Scarlett had always envied the Tarleton girls their free-and-easy ways with their mother. Now she saw the same easiness between Maureen and her children. And she knew that she, too, was welcome to laugh with Maureen, to tease and be teased, to share in the bounteous affection that Jamie’s wife showered on everyone around her.

At that moment Scarlett’s near-worship of her serene, self-contained mother shivered and suffered a tiny crack, and she began to free herself of the guilt she’d always felt because she couldn’t live up to her mother’s teachings. Perhaps it was all right if she wasn’t a perfect lady. The idea was too rich, too complicated. She’d think about it later. She didn’t want to think about anything now. Not yesterday, not tomorrow. The only thing that mattered was this moment and the happiness it held, the music and singing and clapping and dancing.

After the formal rituals of Charleston’s balls, the spontaneous home-made pleasures were intoxicating. Scarlett breathed deep of the joy and laughter around her, and it giddied her.

Matt’s daughter Peggy showed her the simplest steps of the reel, and there was, in some strange way, a rightness to learning from a seven-year-old child. And a rightness to the outspoken encouragement and even the teasing of the others, adults and children alike, because it was the same for Peggy as it was for her. She danced until her knees were wobbly, then she collapsed, laughing, in a heap on the floor at Old James’ feet, and he patted her head as if she were a puppy, and that made her laugh all the more, until she was gasping for breath when she cried out, “I’m having so much fun!”

There had been very little fun in Scarlett’s life, and she wanted it to last forever, this clean, uncomplicated joyfulness. She looked at her big, happy cousins, and she was proud of their strength and vigor and talent for music and for life. “We’re a fine lot, we O’Haras. There’s none can touch us.” Scarlett heard her father’s voice, boasting, saying the words he had so often said to her, and she knew for the first time what he had meant.

“Ah, Jamie, what a wonderful night this was,” she said when he was walking her home. Scarlett was so tired she was practically stumbling, but she was chattering like a magpie, too exhilarated to accept the peaceful silence of the sleeping city. “We’re a fine lot, we O’Haras.”

Jamie laughed. His strong hands caught her around the waist and he lifted her up and swung her in a giddy circle. “There’s none can touch us,” he said when he set her down.

“Miss Scarlett . . . Miss Scarlett!” Pansy woke her at seven with a message from her grandfather. “He wants you right this minute.”

The old soldier was formally dressed and fresh-shaven. He looked disapprovingly at Scarlett’s hastily combed hair and dressing gown from his imperial position in the great armchair at the head of the dining room table.

“My breakfast is unsatisfactory,” he announced.

Scarlett stared at him, slack-jawed. What did his breakfast have to do with her? Did he think she’d cooked it? Maybe he had lost his mind. Like Pa. No, not like Pa. Pa had had more than he could bear, that’s all, and so he retreated to a time and a world where the terrible’ things hadn’t happened. He was like a confused child. But there’s nothing confused or child-like about Grandfather. He knows exactly where and who he is and what he’s doing. What does he mean by waking me up after only a couple of hours’ sleep and complaining to me about his breakfast?

Her voice was carefully calm when she spoke. “What’s wrong with your breakfast, Grandfather?”

“It’s tasteless and it’s cold.”

“Why don’t you send it back to the kitchen, then? Tell them to bring what you want and make sure it’s hot.”

“You do it. Kitchens are women’s business.”

Scarlett put her hands on her hips. She looked at her grandfather with eyes as steely as his. “Do you mean to tell me that you got me out of bed to send a message to your cook? What do you take me for, some kind of servant? Order your own breakfast or starve, it’s all the same to me. I’m going back to bed.” Scarlett turned with a flounce.

“That bed belongs to me, young woman, and you occupy it by my grace and favor. I expect you to obey my orders as long as you’re under my roof.”

She was in a fine rage now, all hope of sleep gone. I’ll pack my things this minute, she thought. I don’t have to put up with this.

The seductive aroma of fresh coffee stopped her before she spoke. She’d have coffee first, then tell the old man off . . . And she’d better think a minute. She wasn’t ready to leave Savannah yet. Rhett must know, by now, that she was here. And she should get a message about Tara from the Mother Superior any minute.

Scarlett walked to the bell pull by the door. Then she took a chair at her grandfather’s right. When Jerome came in, she glared at him. “Give me a cup for my coffee. Then take this plate away. What is it, Grandfather, cornmeal mush? Whatever it is, Jerome, tell the cook to eat it herself. After she fixes some scrambled eggs and ham and bacon and grits and biscuits. With plenty of butter. And I’ll have a pitcher of thick cream for my coffee right this minute.”

Jerome looked at the erect old man, silently urging him to put Scarlett in her place. Pierre Robillard looked straight ahead, not meeting his butler’s eyes.

“Don’t stand there like a statue,” Scarlett snapped. “Do as you’re told.” She was hungry.

So was her grandfather. Although the meal was as silent as his birthday dinner had been, this time he ate everything that was brought to him. Scarlett watched him suspiciously from the corner of her eye. What was he up to, the old fox? She couldn’t believe that there wasn’t something behind this charade. In her experience, getting what you wanted from servants was the easiest thing in the world. All you had to do was shout at them. And Lord knows Grandfather’s good at terrifying people. Look at Aunt Pauline and Aunt Eulalie.

Look at me, for that matter. I hopped out of bed quick enough when he sent for me. I’ll not do that again.

The old man dropped his napkin by his empty plate. “I’ll expect you to be suitably dressed for future meals,” he said to Scarlett. “We shall leave the house in precisely one hour and seven minutes to go to church. That should provide adequate time for your grooming.”

Scarlett hadn’t intended to go to church at all, now that her aunts weren’t there to expect it and she’d gotten what she wanted from the Mother Superior. But her grandfather’s high-handedness had to be stopped. He was violently anti-Catholic, according to her aunts.

“I didn’t know you attended Mass, Grandfather,” she said. Sweetness dripped from the words.

Pierre Robillard’s thick white brows met in a beetling frown. “You do not subscribe to that papist idiocy like your aunts, I hope.”

“I’m a good Catholic, if that’s what you mean. And I’m going to Mass with my cousins, the O’Haras. Who—by the way—have invited me to come stay with them any time I want, for as long as I like.” Scarlett stood and marched in triumph from the room. She was halfway up the stairs before she remembered that she shouldn’t have eaten anything before Mass. No matter. She didn’t have to take Communion if she didn’t want to. And she’d certainly showed Grandfather. When she reached her room, she did a few steps of the reel that she’d learned the night before.

She didn’t for a minute believe that the old man would call her bluff about staying with her cousins. Much as she loved going to the O’Haras’ for music and dancing, there were far too many children there to make a visit possible. Besides, they didn’t have any servants. She couldn’t get dressed without Pansy to lace her stays and fix her hair.

I wonder what he’s really up to, she thought again. Then she shrugged. She’d probably find out soon enough. It wasn’t really important. Before he came out with it, Rhett would probably have come for her anyhow.

40

One hour and four minutes after Scarlett went up to her room, Pierre Auguste Robillard, soldier of Napoleon, left his beautiful shrine of a house to go to church. He wore a heavy overcoat and a wool scarf, and his thin white hair was covered with a tall hat made of sable that had once belonged to a Russian officer who died at Borodino. Despite the bright sun and the promise of spring in the air, the old man’s thin body was cold. Still, he walked stiffly erect, seldom using the malacca cane he carried. He nodded in a correct abbreviated bow to the people who greeted him on the street. He was very well known in Savannah.

At the Independent Presbyterian Church on Chippewa Square he took his place in the fifth pew from the front, the place that had been his ever since the gala dedication of the church nearly sixty years earlier. James Monroe, then president of the United States, had been at the dedication and had asked to be introduced to the man who had been with Napoleon from Austerlitz to Waterloo. Pierre Robillard had been gracious to the older man, even though a President was nothing impressive to a man who had fought alongside an Emperor.

When the service ended, he had a few words with several men who responded to his gesture and hurried to join him on the steps of the church. He asked a few questions, listened to a great many answers. Then he went home, his stern face almost smiling, to nap until dinner was served to him on a tray. The weekly outing to church grew more tiring all the time.

He slept lightly, as the very old do, and woke before Jerome brought his tray. While he waited for it, he thought about Scarlett.

He had no curiosity about her life or her nature. He hadn’t given her a thought for many years, and when she appeared in his room with his daughters he was neither pleased nor displeased to see her. She caught his attention only when Jerome complained to him about her. She was causing disruption in the kitchen with her demands, Jerome said. And she would cause Monsieur Robillard’s death if she continued to insist on adding butter and gravy and sweets to his bills.

She was the answer to the old man’s prayer. He had nothing to look forward to in his life except more months or years of the unchanging routine of sleep and meals and the weekly excursion to church. It did not disturb him that his life was so featureless; he had his beloved wife’s likeness before his eyes and the certainty that, in due time, he would be reunited with her after death. He spent the days and nights dreaming of her when he slept and turning memories of her in his mind when he was awake. It was enough for him. Almost. He did miss having good food to eat, and in recent years it had been tasteless, cold when it wasn’t burnt, and of a deadly monotony. He wanted Scarlett to change that.

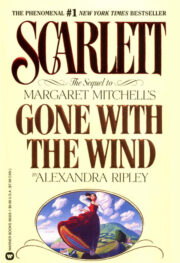

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.