“Colum’s right about one thing,” said Kathleen. “Daniel’s given you the blessing of the head of the house. When you can’t bear another minute of Molly, you’ll have a place here if you want it.”

Scarlett saw her chance. She’d been consumed with curiosity. “Where do you put everybody?” she asked bluntly.

“There’s the loft, divided in two. The boys have their side, Bridie and me the other. And Uncle Daniel took the bed by the fire when Grandmother didn’t want it. I’ll show you.” Kathleen pulled on the back edge of a wooden settle along the wall beyond the stairs, and it folded open and down to reveal a thick mattress covered by a woolen blanket. “He said that’s why he was taking it, to show her she’d missed a good thing, but I’ve always thought he felt too lonely above the room after Aunt Theresa died.”

“ ‘Above the room’?”

“Through there.” Kathleen gestured toward the door. “We fitted it as a parlor, no sense wasting it. The bed’s still there for you any time you’ve the mind.”

Scarlett couldn’t imagine that she ever would. Seven people in one small house were at least four or five too many in her opinion. Particularly such big people. No wonder Pa was called the runt of the litter, she thought, and no wonder he always carried on like he thought he was ten feet tall.

She and Colum visited her grandmother again before going back to Molly’s, but Old Katie Scarlett was asleep by the fire. “Do you think she’s all right?” Scarlett whispered.

Colum just nodded. He waited until they were outside before he spoke. “I saw the stewpot on the table, and it was almost empty. She’ll have fixed Sean’s dinner and shared it since we were there. She always has a small nap after meals.”

The tall hedgerows that bordered the boreen were sweet with blossoms of hawthorn, and the singing of birds poured down from the branches at the top, two feet above Scarlett’s head. It was wonderful to walk along, in spite of the wet ground. “Is there a boreen to the Boyne, Colum? You said you’d take me.”

“And so I did. In the morning, if it please you. I promised Molly I’d have you home in good time today. She’s having a tea party in your honor.”

A party! For her! What a good idea it was, coming to meet her kinfolks before she settled in Charleston.

51

The food was good, but that’s the only good thing I can find to say, Scarlett thought. She smiled brilliantly and shook hands with each of Molly’s departing guests. God’s nightgown! What limp droopy fingers these women have, and they all talk like they’ve got something stuck in their throat. I’ve never seen such a tacky bunch of people in all my born days.

The competitive overrefinement of provincial, would-be gentry was something Scarlett had never run into. There was an earthy forthrightness to Clayton County landowners and a true aristocracy that scorned pretension in Charleston and in the circle she’d thought of as “Melly’s friends” in Atlanta. The elevated little finger of the hand lifting the teacup and the dainty, mouse-sized bites of scones and sandwiches that characterized Molly and her acquaintances seemed as ridiculous to her as in fact they were. She had eaten the excellent food with excellent appetite and ignored the hinted invitations to deplore the vulgarity of people who dirtied their hands with farm work. “What does Robert do, Molly—wear kid gloves all the time?” she’d asked, delighted to see that lines did show up in Molly’s perfect skin when she frowned.

I reckon she’ll have a few words to say to Colum about bringing me here, but I don’t care. It served her right for talking about me like I wasn’t an O’Hara at all, or her either. And where did she come up with that idea that a plantation is the same thing as—what did she call it?—an English manor. I might have to have a few words with Colum myself. Their faces were a treat, though, when I told them all our servants and field hands were always black. I don’t think they’ve ever heard of dark skin, much less seen any. This is a strange place, all around.

“What a lovely party, Molly,” said Scarlett. “I declare I ate till I could fairly pop. I think I might just take a little rest up in my room for a while.”

“You must, naturally, do whatever you like, Scarlett. I had the boy bring around the trap so we could have a drive, but if you’d prefer to sleep . . .”

“Oh, no, I’d love to go out. Can we go to the river, do you think?” She’d planned to get away from Molly, but it was too good a chance to miss. The truth was she’d rather ride to see the Boyne than walk there. She didn’t trust Colum one bit when he said it wasn’t far.

Rightly so, as it turned out. Wearing yellow gloves to match the yellow spokes of the trap’s tall wheels, Molly drove all the way back to the main road, then through the village. Scarlett looked at the row of dispirited-looking buildings with interest.

The trap rolled through the biggest gates Scarlett had ever seen, tremendous creations of wrought iron topped with gold spear points, each side centered by a gold-surrounded brightly colored plaque of intricate design. “The Earl’s coat of arms,” said Molly lovingly. “We’ll drive to the Big House and see the river from the garden. It’s all right, he’s not there, and Robert got permission from Mr. Alder-son.”

“Who’s that?”

“The Earl’s land agent. He manages the entire manor. Robert knows him.”

Scarlett tried to look impressed. Clearly, she was supposed to be bowled over, though she couldn’t think why. What could be so important about an overseer? They were only hired help.

Her question was answered after a long drive on a perfectly straight, wide, gravelled road through spreading expanses of clipped lawn that reminded her for a moment of the great sweeping terraces of Dunmore Landing. The thought was pushed aside by her first sight of the Big House.

It was immense, not one building, it seemed, but a cluster of crenellated roofs and towers and walls. It was more like a small city than like any house Scarlett had ever seen or even heard of. She understood why Molly was so respectful of the agent. Managing a place like this would take more people and more work than the biggest plantation that had ever been. She craned her neck to look up at the stone walls and marble-framed tracery windows. The mansion Rhett had built for her was the largest and—to Scarlett’s mind—most impressive residence in Atlanta, yet it could be put down in one corner of this place and hardly take up enough room to be noticed. I’d love to see the inside . . .

Molly was horrified that Scarlett would even ask. “We have permission to walk in the garden. I’ll tie the pony to that hitching post, and we’ll go through the gate there.” She pointed to a steeply pointed arched entry. The iron gate was ajar. Scarlett jumped down from the trap.

The archway led through to a gravelled terrace. It was the first time Scarlett had ever seen gravel raked into a pattern. She was almost timid about walking on it. Her footprints would ruin the perfection of the S-curves formed by the raking. She looked apprehensively at the garden beyond the terrace. Yes, the paths were gravel. And raked. Not in curves, thank heaven, but still there wasn’t a footprint to be seen. I wonder how they do that? The man with the rake has to have feet. She took a deep breath and crunched boldly onto the terrace and across it to the marble steps into the garden. The sound of her boots on the gravel was as loud as gunfire to her ears. She was sorry she’d come.

Where was Molly anyway? Scarlett turned around as quietly as she could. Molly was walking carefully, fitting her steps into the prints Scarlett had left. It made her feel much better that her cousin—for all her airs—was even more intimidated than she was. She looked up at the house, waiting for Molly to catch up. It seemed much more human from this side. There were French windows from the terrace to the rooms. Closed and curtained, but not too big to walk in and out of, not overwhelming like the doors on the front of the house. It was possible to believe that people might live here, not giants.

“Which way is the river?” Scarlett called to her cousin. She wasn’t going to let an empty house make her whisper.

But she didn’t care to linger, either. She refused Molly’s suggestion that they walk through all the paths and all the gardens. “I just want to see the river. I’m bored sick of gardens; my husband makes too much fuss about them.” She fended off Molly’s transparent curiosity about her marriage while they followed the center path toward the trees that marked the end of the garden.

And then suddenly it was there, through an artfully natural-looking gap between two clumps of trees. Brown and gold, like no water Scarlett had ever seen. The sunlight lay on top of the river like molten gold swirling in slow eddies of water as dark as brandy. “It’s beautiful,” she said aloud, her voice soft. She hadn’t expected beauty.

To hear Pa talk it should be red from all the blood that was spilled, and rushing and wild. But it hardly looks like it’s moving at all. So this is the Boyne. She’d heard about it all her life and now she was close enough to reach down and touch it. Scarlett felt an emotion unknown to her, something she couldn’t name. She searched for some definition, some understanding; it was important, if she could just find it . . .

“That’s the view,” Molly said in her cramped, most refined diction. “All the best houses have a view from their gardens.”

Scarlett wanted to hit her. She’d never find it now, whatever she’d been looking for. She looked where Molly indicated and saw a tower on the other side of the river. It was like the ones she’d seen from the train, made of stone and part crumbled away. Moss stained the base of it and vines clung to its sides. It was much bigger than she’d thought they would be when she saw them at a distance; it looked like it might be as much as thirty feet across and twice that high. She had to agree with Molly that it was a romantic view.

“Let’s go,” she said after one more look at the river. All of a sudden she felt very tired.

“Colum, I think I’m going to kill dear cousin Molly. If you could have heard that horrible Robert last night at dinner telling us how privileged we were to walk on the Earl’s dumb garden paths. He must have said it about seven hundred times, and every single time Molly chirped away for ten minutes about what a thrill it was.

“And then, this morning, she practically swooned when she saw me in these Galway clothes. No chirpy little lady voice then, let me tell you. She lectured me about ruining her position and being an embarrassment to Robert. To Robert! He should be embarrassed every time he sees his dumb fat face in a looking glass. How dare Molly lecture me about disgracing him?”

Colum patted Scarlett’s hand. “She’s not the best companion I’d wish for you, Scarlett darling, but Molly has her virtues. She did lend us the trap for the day, and we’ll have a grand outing with no thought of her to cloud it. Look at the blackthorn flowers in the hedges, and the wild cherries blooming their hearts out in that farmyard. It’s too fine a day to waste on rancor. And you look like a lovely Irish lass in your striped stockings and red petticoat.”

Scarlett stretched out her feet and laughed. Colum was right. Why should she let Molly ruin her day?

They went to Trim, an ancient town with a rich history that Colum knew would interest Scarlett not at all. So he told her instead about Market Day every Saturday, just like Galway, only, he had to acknowledge, considerably smaller. But with a fortune-teller most Saturdays, something you seldom found in Galway, and a glorious fortune promised if you paid tuppence, reasonable happiness for a penny, and tribulation foretold only if your pocket could produce merely a ha’penny.

Scarlett laughed—Colum could always make her laugh—and touched the drawstring bag hanging between her breasts. It was hidden by her shirt and her Galway blue cloak. No one would ever know she was wearing two hundred dollars in gold instead of a corset. The freedom was almost indecent. She had not been out of the house without stays since she was eleven years old.

He showed her Trim’s famous castle, and Scarlett pretended interest in the ruins. Then he showed her the store where Jamie had worked from the time he was sixteen until he went to Savannah at the age of forty-two, and Scarlett’s interest was real. They talked with the shopkeeper, and of course nothing would do but to close the shop and accompany the owner upstairs to meet his wife, who would surely die from the sorrow of it if she couldn’t hear the news from Savannah straight from Colum’s own lips and meet the visiting O’Hara who was already the talk of the countryside for her beauty and her American charm.

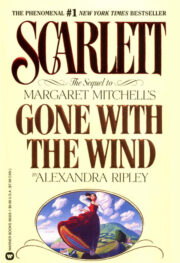

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.