Believe me, Rhett’s letter began, when I say that you have my deepest sympathy in your bereavement. Mammy’s death is a great loss. I am grateful that you notified me in time for me to see her before she went.

Scarlett looked up in a rage from the thick black pen strokes and spoke aloud. “ ‘Grateful,’ my foot! So you could lie to her and to me, you varmint.” She wished she could burn the letter and throw the ashes in Rhett’s face, shouting the words at him. Oh, she’d get even with him for shaming her in front of Suellen and Will. No matter how long she had to wait and plan, she’d find a way somehow. He had no right to treat her that way, to treat Mammy that way, to make a sham out of her last wishes like that.

I’ll burn it now, I won’t even read the rest, I don’t have to put my eyes to any more of his lies! Her hand fumbled for the box of matches, but when she held it, she dropped it at once. I’ll die of wondering what was in it, she admitted to herself, and she lowered her head to read on.

She would find her life unaltered, Rhett stated. The household bills would be paid by his lawyers, an arrangement he had made years before, and all moneys drawn from Scarlett’s bank account by check would be replaced automatically. She might want to instruct any new shops where she opened accounts about the procedure all her current shopping places used: they sent their bills directly to Rhett’s lawyers. Alternatively, she could pay her bills by check, the amount being replaced in her bank.

Scarlett read all this with fascination. Anything that had to do with money always interested her, always had, since the day when she was forced by the Union Army to discover what poverty was. Money was safety, she believed. She hoarded the money she earned herself, and now, viewing Rhett’s open-handed generosity, she was shocked.

What a fool he is, I could rob him blind if I wanted to. Probably his lawyers have been cooking those account books for ages, too.

Then—Rhett must be powerfully rich if he can spend without caring where it goes. I always knew he was rich. But not this rich. I wonder how much money he’s got.

Then—he does still love me, this proves it. No man would ever spoil a woman the way Rhett spoiled me all these years unless he loved her to distraction, and he’s going to keep on giving me every thing and anything I want. He must still feel the same, or he’d rein in. Oh, I knew it! I knew it. He didn’t mean all those things he said. He just didn’t believe me when I told him I know now that I love him.

Scarlett held Rhett’s letter to her cheek as if she were holding the hand that had written it. She’d prove it to him, prove she loved him with all her heart, and then they’d be so happy—the happiest people in the whole world!

She covered the letter with kisses before she put it carefully away in a drawer. Then she set to work on the store accounts with enthusiasm. Doing business invigorated her. When a maid tapped on the door and timidly asked about supper, Scarlett barely glanced up. “Bring me something on a tray,” she said, “and light the fire in the grate.” It was chilly with darkness falling, and she was hungry as a wolf.

She slept extremely well that night. The store had done well in her absence, and the supper was satisfying in her stomach. It was good to be home, especially with Rhett’s letter resting safely under her pillow.

She woke and stretched luxuriously. The crackle of paper beneath her pillow made her smile. After she rang for her breakfast tray, she began to plan her day. First to the store. It must be low on stock of a lot of things; Kershaw kept the books well enough, but he didn’t have the sense of a pea hen. He’d run right out of flour and sugar before he thought about refilling the kegs, and he probably hadn’t ordered a speck of kerosene or so much as a stick of kindling even though it was getting colder every day.

She hadn’t gotten around to the newspapers last night, either, and going to the store would save her all that boring reading. Anything worth knowing about in Atlanta she’d pick up from Kershaw and the clerks. There was nothing like a general store for collecting all the stories that were going around. People loved to talk while they were waiting for their goods to be wrapped. Why, half the time she already knew what was on the front page before the paper ever got printed; she could probably throw away the whole batch on her desk and not miss a thing.

Scarlett’s smile disappeared. No, she couldn’t. There’d be a piece about Melanie’s burial, and she wanted to see it.

Melanie . . .

Ashley . . .

The store would have to wait. She had other obligations to see to first.

Whatever possessed me to promise Melly that I’d take care of Ashley and Beau?

But I promised. I’d best go there first. And I’d better take Pansy to make everything proper. Tongues must be wagging all over town after that scene at the graveyard. No sense adding to the gossip by seeing Ashley alone. Scarlett hurried across the thick carpet to the embroidered bell pull and jerked it savagely. Where was her breakfast?

Oh, no, Pansy was still at Tara. She’d have to take one of the other servants; that new girl, Rebecca, would do. She hoped Rebecca could help her dress without making too big a mess of it. She wanted to hurry, now, to get going and get her duty over with.

When her carriage pulled up in front of Ashley and Melanie’s tiny house on Ivy Street, Scarlett saw that the mourning wreath was gone from the door, and the windows were all shuttered.

India, she thought at once. Of course. She’s taken Ashley and Beau to live at Aunt Pittypat’s. She must be mighty pleased with herself.

Ashley’s sister India was, and always had been, Scarlett’s implacable enemy. Scarlett bit her lip and considered her dilemma. She was sure that Ashley must have moved to Aunt Pitty’s with Beau; it was the most sensible thing for him to do. Without Melanie, and now with Dilcey gone, there was no one to run Ashley’s house or mother his son. At Pittypat’s there was comfort, an orderly household, and constant affection for the little boy from women who had loved him all his life.

Two old maids, thought Scarlett with disdain. They’re ready to worship anything in pants, even short pants. If only India didn’t live with Aunt Pitty. Scarlett could manage Aunt Pitty. The timid old lady wouldn’t dare talk back to a kitten, let alone Scarlett.

But Ashley’s sister was another matter. India would just love to have a confrontation, to say nasty things in her cold, spitting voice, to show Scarlett the door.

If only she hadn’t promised Melanie—but she had. “Drive me to Miss Pittypat Hamilton’s,” she ordered Elias. “Rebecca, you go on home. You can walk.”

There would be chaperones enough at Pitty’s.

India answered her knock. She looked at Scarlett’s fashionable fur-trimmed mourning costume, and a tight, satisfied smile moved her lips.

Smile all you like, you old crow, thought Scarlett. India’s mourning gown was unrelieved dull black crape, without so much as a button to decorate it. “I’ve come to see how Ashley is,” she said.

“You’re not welcome here,” India said. She began to close the door.

Scarlett pushed against it. “India Wilkes, don’t you dare slam that door in my face. I made a promise to Melly, and I’ll keep it if I have to kill you to do it.”

India answered by putting her shoulder to the door and resisting the pressure of Scarlett’s two hands. The undignified struggle lasted for only a few seconds. Then Scarlett heard Ashley’s voice.

“Is that Scarlett, India? I’d like to talk with her.”

The door swung open, and Scarlett marched in, noting with pleasure that India’s face was mottled with red splotches of anger.

Ashley came forward into the hallway to greet her, and Scarlett’s brisk steps faltered. He looked desperately ill. Dark circles ringed his pale eyes, and deep lines ran from his nostrils to his chin. His clothes looked too big for him; his coat hung from his sagging frame like broken wings on a black bird.

Scarlett’s heart turned over. She no longer loved Ashley the way she had for all those years, but he was still part of her life. There were so many shared memories, over so much time. She couldn’t bear to see him in such pain. “Dear Ashley,” she said gently, “come and sit down. You look tired.”

They sat on a settee in Aunt Pitty’s small, fussy, cluttered parlor for more than an hour. Scarlett spoke seldom. She listened while Ashley talked, repeating and interrupting himself in a confused zigzag of memories. He recounted stories of his dead wife’s kindness, unselfishness, nobility, her love for Scarlett, for Beau, and for him. His voice was low and without expression, bleached by grief and hopelessness. His hand groped blindly for Scarlett’s, and he grasped it with such despairing strength that her bones rubbed together painfully. She compressed her lips and let him hold on to her.

India stood in the arched doorway, a dark, still spectator.

Finally Ashley interrupted himself and turned his head from side side like a man blinded and lost. “Scarlett, I can’t go on without her,” he groaned. “I can’t.”

Scarlett pulled her hand away. She had to break through the shell of despair that bound him, or it would kill him, she was sure. She stood and leaned down over him. “Listen to me, Ashley Wilkes,” she said. “I’ve been listening to you pick over your sorrows all this time, and now you listen to mine. Do you think you’re the only person who loved Melly and depended on her? I did, more than I knew, more than anybody knew. I expect a lot of other people did, too. But we’re not going to curl up and die for it. That’s what you’re doing. And I’m ashamed of you.

“Melly is, too, if she’s looking down from heaven. Do you have any idea what she went through to have Beau? Well, I know what she suffered, and I’m telling you it would have killed the strongest man God ever made. Now you’re all he’s got. Is that what you want Melly to see? That her boy is all alone, practically an orphan, because his Pa feels too sorry for himself to care about him? Do you want to break her heart, Ashley Wilkes? Because that’s what you’re doing.” She caught his chin in her hand and forced him to look at her.

“You pull yourself together, do you hear me, Ashley? You march yourself out to the kitchen and tell the cook to fix you a hot meal. And you eat it. If it makes you throw up, eat another one. And you find your boy and take him in your arms and tell him not to be scared, that he has a father to take care of him. Then do it. Think about somebody besides yourself.”

Scarlett wiped her hand on her skirt as if it were soiled by Ashley’s grip. Then she walked from the room, pushing India out of the way.

As she opened the door to the porch, she could hear India: “My poor, darling Ashley. Don’t pay any attention to the horrible things Scarlett said. She’s a monster.”

Scarlett stopped, turned. She withdrew a calling card from her purse and dropped it on a table. “I’m leaving my card for you, Aunt Pitty,” she shouted, “since you’re afraid to see me in person.”

She slammed the door behind her.

“Just drive, Elias,” she told her coachman. “Anywhere at all.” She couldn’t stand to stay in that house one single minute more. What was she going to do? Had she gotten through to Ashley? She’d been so mean—well, she had to be, he was being drowned in sympathy and pity—but had it done any good? Ashley adored his son, maybe he’d pull himself together for Beau’s sake. “Maybe” wasn’t good enough. He had to. She had to make him do it.

“Take me to Mr. Henry Hamilton’s law office,” she told Elias.

“Uncle Henry” was terrifying to most women, but not to Scarlett. She could understand that growing up in the same house with Aunt Pittypat had made him a misogynist. And she knew he rather liked her. He said she wasn’t as silly as most women. He was her lawyer and knew how shrewd she was in her business dealings.

When she walked into his office without waiting to be announced, he put down the letter he was reading and chuckled. “Do come in, Scarlett,” he said, rising to his feet. “Are you in a hurry to sue somebody?”

She paced forward and back, ignoring the chair beside his desk. “I’d like to shoot somebody,” she said, “but I don’t know that it would help. Isn’t it true that when Charles died, he left me all his property?”

“You know it is. Stop that fidgeting and sit down. He left the warehouses near the depot that the Yankees burned. And he left some farmland outside of town that will be in town before too long, the way Atlanta has been growing.”

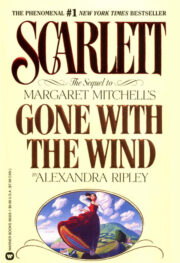

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.