The weather turned rainy, not the brief showers or misty days that Scarlett had gotten used to, but real torrents of rain that lasted sometimes for three to four hours. The farmers complained about the soil compacting if they walked on the newly cleared fields to spread the cartloads of manure Scarlett had bought. But Scarlett, forcing herself to walk daily to check the progress at the Big House, blessed the mud on the ungravelled drive because it cushioned her swollen feet. She gave up boots altogether and kept a bucket of water inside her front door to rinse her feet when she came in. Colum laughed when he saw it. “The Irish in you is strengthening every day, Scarlett darling. Did you learn that from Kathleen?”

“From the cousins when they came in from the fields. They always washed the earth off their feet. I figured it was because Kathleen would be mad if they tracked up her clean floor.”

“Not a bit of it. They did it because Irishmen—and women too—have done it as long as anyone’s great-grandfather can remember. Do you shout ‘seachain’ before you throw the water out?”

“Don’t be silly, of course not. I don’t put a bowl of milk on the doorstep every night either. I don’t believe I’m likely to drench any fairies or give them supper. That’s all childish superstition.”

“So you say. But one day a pooka’s going to get you for your insolence.” He looked nervously under her bed and pillow.

Scarlett had to laugh. “All right, I’ll bite, Colum. What’s a pooka? Second cousin to a leprechaun, I suppose.”

“The leprechauns would shudder at the suggestion. A pooka is a fearful creature, malicious and sly. He’ll curdle your cream in an instant or tangle your hair with your own brush.”

“Or swell my ankles, I guess. That’s as malicious as anything I’ve ever been through.”

“Poor lamb. How much longer?”

“About three weeks. I’ve told Mrs. Fitzpatrick to clean out a room for me and order in a bed.”

“Are you finding her helpful, Scarlett?”

She had to admit she was. Mrs. Fitzpatrick wasn’t so taken with her position that she minded working hard herself. Plenty of times Scarlett had found her scrubbing the stone floor and stone sinks in the kitchen herself to show the maids how to do it.

“But Colum, she’s been spending money like there’s no end to it. Three maids I’ve got up there already, just to get things nice enough so that a cook will be willing to come. And a stove the likes of which I’ve never seen, all kinds of burners and ovens and a well thing for hot water. It cost almost a hundred pounds, and ten more to haul it from the railroad. Then, after all that, nothing would do but to have the smith make all kinds of cranes and spits and hooks for the fireplace. Just in case the cook doesn’t like stove ovens for some things. Cooks must be more spoiled than the Queen.”

“More useful, too. You’ll be glad when you sit down to your first good meal in your own dining room.”

“So you say. I’m happy enough with Mrs. Kennedy’s meat pies. I ate three last night. One for me and two for this elephant inside me. Oh, I’ll be so happy when this is over . . . Colum?” He’d been away, and Scarlett didn’t feel as easy with him as she used to, but she needed to ask him anyhow. “Have you heard about this ‘The O’Hara’ business?”

He had and he was proud of her and he thought it was deserved. “You’re a remarkable woman, Scarlett O’Hara. No one who knows you thinks otherwise. You’ve ridden over blows that would fell a lesser woman—or a man as well. And you’ve never moaned or asked pity.” He smiled roguishly. “You’ve done what’s near miraculous, too, getting all these Irish to work the way they have. And spitting in the eyes of the English officer—well, they say you put out the sight in one of them from a hundred paces.”

“That’s not true!”

“And why should a grand tale be tarnished by the truth? Old Daniel himself was the first who called you The O’Hara, and he was there.”

Old Daniel? Scarlett flushed with pleasure.

“You’ll be swapping stories with Finn MacCool’s ghost one day soon, to hear the talk. The whole countryside’s richer for having you here.” Colum’s light tone darkened. “There’s one thing I want to caution you about, Scarlett. Don’t turn up your nose at people’s beliefs; it’s insulting to them.”

“I never do! I go to Mass every Sunday, even though Father Flynn looks like he might fall asleep any minute.”

“I’m not speaking of the Church. I’m talking about the fairies and the pookas and that. One of the mighty deeds you’re praised for is moving back to the O’Hara land when everyone knows it’s haunted by the ghost of the young lord.”

“You can’t be serious.”

“I can, and I am. It matters not whether you believe or not. The Irish people do. If you mock what they believe in, you’re spitting in their eyes.”

Scarlett could see that, silly as it all was. “I’ll hold my tongue, and I won’t laugh, unless it’s at you, but I’m not going to holler before I empty the bucket.”

“You don’t have to. They’re saying you’re so respectful you whisper real soft.”

Scarlett laughed until she disturbed the baby and was kicked mightily. “Now look what you did, Colum. My insides are black and blue. But it’s worth it. I haven’t laughed like that since you went away. Stay home for a while, will you?”

“That I will. I want to be one of the first to see this elephant child of yours. I’m hoping you’ll name me a godfather.”

“Can you do that? I’m counting on you to baptize him or her or them.

Colum’s smile vanished. “I cannot do that, Scarlett darling. Anything else you ask me, though it be to fetch you the moon for a bauble. I do not perform the sacraments.”

“Whyever not? That’s your job.”

“No, Scarlett, that’s the job of a parish priest or on special occasions a bishop or archbishop or more. I’m a missionary priest, working to ease the sufferings of the poor. I perform no sacraments.”

“You could make an exception.”

“That I could not, and that’s an end of it. But the grandest of godfathers I’ll be, if asked, and see to it that Father Flynn doesn’t drop the babe in the font or on the floor, and I’ll teach him his catechism with such eloquence that he’ll think he’s learning a limerick instead. Do ask me, Scarlett darling, or you’ll break my yearning heart.”

“Of course I’ll ask you.”

“Then I’ve got what I came for. Now I can go beg a meal in a house that adds salt.”

“Go on, then. I’m going to rest until the rain stops then go see Grandmother and Kathleen while I can. The Boyne’s almost too high to ford already.”

“One more promise, and I’ll stop fussing you. Stay in your house Saturday evening with your door shut tight and your curtains drawn. It’s All Hallows’ Eve, and the Irish believe all the fairies are out from all the time since the world began. And, as well, goblins and ghosts and spirits carrying their heads under their arms and all manner of unnatural things. Pay heed to the customs and close yourself in safe from seeing them. None of Mrs. Kennedy’s meat pies. Boil some eggs. Or, if you’re really feeling Irish, have a supper of whiskey washed down with ale.”

“No wonder they see spooks! But I’ll do as you say. Why don’t you come over?”

“And be in the house all night with a seductive lass like you? I’d have me collar taken away.”

Scarlett stuck out her tongue at him. Seductive, indeed. To an elephant maybe.

The trap wobbled alarmingly when she crossed the ford and she decided not to stay long at Daniel’s. Her grandmother was looking drowsy, so Scarlett didn’t sit down. “I just stopped in for a second, Grandmother, I won’t keep you from your nap.”

“Come kiss me goodbye, then, Young Katie Scarlett. You’re a lovely girl to be sure.” Scarlett embraced the tough tiny body gently, kissed the old cheek firmly. Almost at once her Grandmother’s chin dropped on her chest.

“Kathleen, I can’t stay long, the river’s rising so. By the time it’s down I doubt I’ll be able to get in the trap at all. Have you ever seen such a giant baby?”

“Yes, I have, but you don’t want to hear it. Every baby’s the only baby is my observation of mothers. You’ll have a minute for a bite and a cup of tea?”

“I shouldn’t but I will. May I take Daniel’s chair? It’s the biggest.”

“You’re welcome to it. Daniel’s never been so warm towards any of us as he is to you.”

The O’Hara, thought Scarlett. It warmed her even more than the tea and the smoke-smelling clean fire.

“Have you the time to see Grandmother, Scarlett?” Kathleen put a stool beside Daniel’s chair with tea and cake on it.

“I went there first. She’s napping now.”

“That’s grand, then. It would be a pity if she missed telling you goodbye. She’s taken out her shroud from the box where she keeps her treasures. She’ll be dead ere long.”

Scarlett stared at Kathleen’s serene face. How can she say things like that in the same tone of voice as talking about the weather or something? And then drink tea and eat cake as calm as you please?

“We’re all hoping for a few dry days first,” Kathleen went on. “The roads are that deep in mud people will have trouble getting to the wake. But we’ll have to take what comes.” She noticed Scarlett’s horror and misinterpreted it.

“We’ll all miss her, Scarlett, but she’s ready to go, and those that live as long as Old Katie Scarlett have a way of knowing when their time is on them. Let me fill your cup, what’s left must be cold.”

It clattered in its saucer as Scarlett put it down. “I really can’t, Kathleen, I’ve got to cross the ford, I have to go.”

“You’ll send word when the pains start? I’ll be happy to stay with you.”

“I will, and thank you. Will you give me a hand up in the trap?”

“Will you take a bit of cake for later? I can wrap it in no time.”

“No, no, thank you, truly, but I’m worried about the water.”

I’m more fretful about going crazy, Scarlett thought when she drove off.

Colum was right, the Irish are all spook-minded. Who’d have thought it of Kathleen? And my own grandmother having a shroud all ready. Heaven only knows what they get up to on Halloween. I’m going to lock the door and nail it shut, too. This stuff is giving me the shivers.

The pony lost its footing for a long terrifying moment crossing the ford.

Might as well face it, no more travel for me until after the baby. I wish I’d accepted the cake.

62

The three country girls stood in the wide doorway of the Big House bedroom Scarlett had chosen for her own. All were wearing big homespun aprons and wide-ruffled mobcaps, but that was the only thing about them that was the same. Annie Doyle was as small and round as a puppy, Mary Moran as tall and ungainly as a scarecrow, Peggy Quinn as neat and pretty as an expensive doll. They were holding hands and crowded together. “We’ll be going now if it’s all the same to you, Mrs. Fitzpatrick, before the heavy rain starts in,” said Peggy. The other girls nodded vigorously.

“Very well,” said Mrs. Fitzpatrick, “but come in early Monday to make up the time.”

“Oh, yes, miss,” they chorused, dropping clumsy curtseys. Their shoes made a racket on the stairs.

“Sometimes I despair,” sighed Mrs. Fitzpatrick, “but I’ve made good maids out of sorrier material than that. At least they’re willing. Even the rain wouldn’t have bothered them if today wasn’t Halloween. I suppose they think if clouds darken the sky it’s the same as nightfall.” She looked at the gold watch pinned on her bosom. “It’s only a little after two . . . Let’s get back where we were. I’m afraid that all this wet will keep us from finishing, Mrs. O’Hara. I wish it weren’t so, but I’m not going to lie to you. We’ve got all the old paper off the walls and everything scrubbed and fresh. But you need new plaster in some spots, and that means dry walls. Then time for the plaster to dry afterwards before the wall is painted or papered. Two weeks just isn’t enough.”

Scarlett’s jaw hardened. “I am going to have my baby in this house, Mrs. Fitzpatrick. I told you that from the beginning.”

Her anger flowed right off Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s sleekness. “I have a suggestion—” said the housekeeper.

“As long as it’s not to go someplace else.”

“On the contrary. I believe with a good fire on the hearth and some cheerful thick curtains at the windows, the bare walls won’t be offensive at all.”

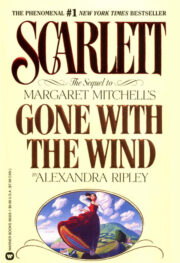

"Scarlett" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Scarlett". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Scarlett" друзьям в соцсетях.