At the sound of my startled gasp, they sprang apart, exposing a good deal of Dorothy’s bosom. Abashed, I started to back away.

“Stay,” the man ordered in a low-pitched growl, and stepped out of the shadows.

I obeyed. Then I simply stared at him.

He was one of the most toothsome gentlemen I had ever seen. Tall and well built, his superb physical condition suggested that he participated in tournaments. I had never attended one, but I had heard that such events were a fixture of court life. Gentlemen vied with each other to show off their prowess with lance and sword. A man who looked this athletic was certain to be a champion jouster. His face, too, was perfection, with regular features, close-cropped auburn hair, and a neatly trimmed beard and mustache.

His eyes were light brown and full of annoyance as his gaze swept over me, from the top of my French hood to the toes of my new embroidered slippers and back up again. By the time they met mine for the second time, approval had replaced irritation.

Sheltered by her companion’s much larger body, Dorothy put her bodice to rights. Still tucking loose strands of dark brown hair into place beneath her headdress, she shoved him aside. Temper contorted her features into an ugly mask. “Begone, Bess!” she hissed. “Have you nothing better to do than spy on me?”

“I did not invade your privacy out of malice. I only wish to retire to my lodgings before His Grace notices me again and I do not know the way.”

The man chuckled. His mouth crinkled at the corners when he smiled at me, making him even more attractive. He doffed his bejeweled bonnet and bowed. “Will Parr at your service, mistress.”

Dorothy slammed the back of her hand into his velvet-clad chest the moment he straightened, preventing him from stepping closer to me. It was no gentle love tap, and if the look she turned my way could have set a fire, I’d have burst into flames on the spot. “That is Baron Parr of Kendal to you, niece.”

I was unimpressed by his title. My father was a baron, too, and so was my uncle, Dorothy’s younger brother. “Lord Parr,” I said, bobbing a brief curtsy in acknowledgment of his courtesy bow, as if we were about to be partners in a dance.

Our eyes met for the third time. I recognized a spark of male interest in his gaze, along with a twinkle of wry amusement. Without warning, butterflies took wing in my stomach. It was the most peculiar sensation, and one I had never experienced before. For a moment my mind went blank. I continued to stare at him, transfixed, my heart racing much too fast.

“If you truly wish to return to your mother,” Dorothy said with some asperity, “then do so. No one here will stop you.”

Her cold voice and harsh words broke the spell. I forced myself to look away from Lord Parr. Although I could not help but be pleased that such a handsome man found me attractive, I knew I should be annoyed with him on Dorothy’s behalf. “How am I to find my way there on my own?” I asked in a small, plaintive voice.

Dorothy’s fingers curled, as if she would like to claw me, but Lord Parr at once offered me his arm. “Allow me to escort you, Mistress Brooke. Brigands haunt the palace at night, you know, men who might be tempted to pluck a pretty flower like you if they found her alone in a dark passageway.”

I looked up at him and smiled. He was just a head taller than I.

“We will both accompany you.” Dorothy clamped a possessive hand on Lord Parr’s other arm with enough force to make him wince. We left the king’s great watching chamber with Lord Parr between us and walked the first little way in silence.

Dorothy’s anger disturbed me. She’d resented the few minutes His Grace had spent talking to me. And now she wanted to keep Lord Parr all to herself. But I was not her rival. And even if I was, I would be gone from court in another day or two.

My steps faltered as comprehension dawned. Dorothy would not be staying much longer either. There was no place at court for maids of honor or ladies of the privy chamber or even chamberers when the king lacked a queen. Dorothy would have to return to her mother—my grandmother Jane at Eaton Bray in Bedfordshire—until the king remarried. What I had interrupted must have been her farewell to her lover.

I glanced her way. Poor Dorothy. It might be many months before she saw Lord Parr again, and I had deprived her of an opportunity, rare at court, for a few moments of privacy.

Worse, although I had not intended it, I had caught Will Parr’s interest. I rushed into speech, uncomfortable with my memory of the profound effect he’d had on me. “Do you think the king has someone in mind to marry?”

“He paid particular attention to you.” Dorothy’s voice dripped venom. She walked a little faster along the torch-lit corridor, forcing us to match her pace.

A wicked thought came into my head. If the king made me his queen and Dorothy were my maid of honor, she’d be obliged to obey my slightest whim. I felt my lips twitch, but I sobered quickly when I remembered that in order to be queen, I’d first have to marry old King Henry. Nothing could make that sacrifice worthwhile!

“I wager Mistress Bassett has the lead,” Lord Parr said in a conversational tone, ignoring Dorothy’s simmering temper.

“Do you think so? Nan has caught His Grace’s eye in the past and nothing came of it.” Dorothy had reined in her emotions with the skill of a trained courtier.

They bandied about a few more names, but none that I recognized. I practiced prudence and held my tongue as we made our way through the maze of corridors and finally stopped before a door identical to dozens of others we’d passed.

“We have arrived,” Dorothy announced with an unmistakable note of relief in her voice. “Here are your lodgings, Bess. We’ll leave you to—”

The door abruptly opened to reveal my father, a big, barrel-chested man with a square face set off by a short, forked beard. His eyebrows lifted when he recognized Dorothy and Lord Parr. “Come in,” he said. “Have a cup of wine.” He fixed Dorothy with a stern look when she tried to excuse herself. “Your sister has been expecting a visit from you ever since we arrived at court.”

Father, Mother, and I had been assigned a double lodging—two large rooms with a fireplace in each and our own lavatory. The outer room was warm and smelled of spiced wine heating on a brazier. Somehow, in only a day, Mother had made the place her own. She’d brought tapestries from Cowling Castle to hang on the walls, including my favorite, showing the story of Paris and Helen of Troy. Our own servants had come with us to make sure we received food and drink in good time and that there was an adequate supply of wood for the fireplaces and coal for the braziers.

Unexpected company never perturbed my mother. She produced bread and cheese and gave the spiced wine a stir with a heated poker before filling goblets for everyone. The drink was a particular favorite of Father’s, claret mixed with clarified honey, pepper, and ginger.

Lord Parr made a face after he took his first sip. “Clary, George? What’s wrong with a good Rhenish wine, perhaps a Brabant?”

“Nothing . . . if you add honey and cloves,” Father said with a laugh. “You are too plain in your tastes, Will.”

“Only in wines.”

I was not surprised that the two men knew each other. They both sat in the House of Lords when Parliament was in session. Standing by the hearth, they broadened their discussion of wines to include Canary and Xeres sack.

I joined Mother and Dorothy, who sat side by side on a long, low-backed bench, exchanging family news in quiet voices. I settled onto a cushion on the floor, leaning against Mother’s knees. At once she reached out to rest one hand on my shoulder.

The sisters did not look much alike. Mother’s hair was light brown and her eyes were blue like mine. She was shorter than Dorothy, too, and heavier, and markedly older, since she’d been married with at least one child of her own by the time Dorothy was born. She might never have been as pretty as her younger sister, but she had always been far kinder.

“Speaking of imports,” Lord Parr said, “I have just brought a troupe of musicians to England from Venice, five talented brothers who were delighted to have found a patron.”

The mention of music caught Mother’s attention. “How fortunate for you,” she said.

“My wife dearly loves music,” Father said. “She insists that all our children learn to play the lute and the virginals and the viol, too.”

“I play the virginals,” Lord Parr confessed, after which he and my mother discussed the merits of that instrument for nearly a quarter of an hour, until Dorothy, with a series of wide but unconvincing yawns, prevailed upon him to escort her to the chamber she shared with several other former maids of honor.

“As you told Bess,” she reminded him, “it is not safe for a woman to walk unescorted through Whitehall Palace at night.” She all but pushed him out the door.

A moment later, she stuck her head back in. “You should take Bess home and keep her there, Anne,” she said to my mother. “The king singled her out and admired her beauty. You know what that means.”

Dorothy’s second departure left behind a startled silence.

“Did His Grace pay uncommon attention to you?” Mother exchanged a worried glance with Father. The concern in her voice made me long to reassure her, but there was no way to hide the truth. Too many people had noted the king’s interest in me and would remember exactly how long we had spoken together.

“He . . . he called me a pretty little thing.” I squirmed under their scrutiny, feeling like a fly caught in a spider’s web.

“And what did you think of him?” Father asked.

“That he is old and fat and diseased and that I want no part of him!”

“Oh, George,” Mother said. “What shall we do? What if His Grace wants Bess to remain at court?”

“He’s not yet said he does, and as I’ve no desire to dangle our daughter in front of him like a carrot before a mule, we will leave for home first thing in the morning.”

“But if he is looking for a wife, as everyone says he is—”

“Then he will have to look elsewhere. It is not as if there are not plenty of willing wenches available.”

“Sixty of them, by my count,” I said. Relief made me giddy. “Although I suppose a few of them, even though they are still unmarried, may already be betrothed.” I had been myself, to a boy I’d met only once, but he’d died. So far, no other arrangement had been made for me.

Mother exchanged another speaking glance with Father but said only, “Are you certain, Bess, that you wish to cut short your first visit to court?”

“I would gladly stay on if I could avoid the king,” I admitted. “But for the nonce, I much prefer to be gone. Perhaps I can return after King Henry makes his selection. Surely, with so many ladies to choose from, it will not take His Grace long to find a new queen.”

2

Cowling Castle, in Kent, had been built by an ancestor of mine for the defense of the realm. Or at least for the defense of our particular section of the north coast of Kent. Way back in the reign of King Richard the Second, a force of Frenchmen and Spaniards had sailed into the Thames Estuary and pillaged villages as far upriver as Gravesend. Vowing they’d never do so again, the third Lord Cobham constructed a mighty fortress to guard the port of Cliffe and the rest of the Hoo Peninsula from invaders.

Nearly two hundred years later, we had little need for walls six feet thick or two moats. Neither of our drawbridges had been raised more than a handful of times that I could remember and never because we were under attack.

After my return to Cowling Castle, I waited expectantly for news of a royal wedding, but weeks stretched into months and still King Henry did not remarry. In the summer, Father began to cast about for a suitable husband for me, but he was in no great hurry. He said he intended to find me a man of strong moral character who was also possessed of sufficient worldly goods to keep me in comfort. In Mother’s opinion, that combination was as scarce as hens’ teeth, but she had no objection to keeping me at home awhile longer. I was content, too. For the most part.

On a fine mid-October afternoon, freed from their lessons in Latin so that they might practice archery, three of my brothers raced across the drawbridge that connected the inner and outer wards. My sister Kate and I followed more slowly. We brought our sewing with us and planned to sit on a wooden bench near the butts to cheer on the competitors.

“Shall we wager on the outcome?” Kate asked as we made our way to the targets set up near the top of the upward-sloping ground. She was a younger version of our mother with the same light brown hair, sparkling blue eyes, and even temperament.

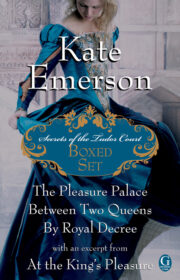

"Secrets of the Tudor Court Boxed Set" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Secrets of the Tudor Court Boxed Set". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Secrets of the Tudor Court Boxed Set" друзьям в соцсетях.