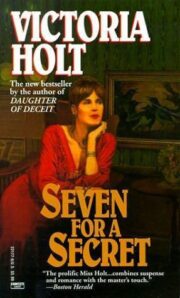

Victoria Holt

Seven for a Secret

Easter Flowers

Very soon after I went to live with my Aunt Sophie, I became acquainted with the strange sisters, Lucy and Flora Lane, and because of what I discovered, for ever after I called their cottage The House of the Seven Magpies.

I often marvel that I might never have known the place but for the trouble over the decoration of the church that long-ago Easter. But perhaps that is not exactly true and it was not entirely due to the flowers they just brought it to a head.

Aunt Sophie had been a rare visitor to our house till then, and there was never a mention of the rift between her and my mother. She lived in Wiltshire, which was a longish journey by train from London and then she would have to get from the capital to Middlemore in Surrey. I imagined she did not feel it worth the effort to come and see us, and my mother certainly thought the journey to Wiltshire too arduous for her, particularly when the result would be a none-too-felicitous encounter with Aunt Sophie.

Aunt Sophie was almost a stranger to me in those early days.

My mother and Aunt Sophie, though sisters, were as unlike each other as any two people could be.

My mother was tall and slim, beautiful too; her features looked as though they had been cut out of marble; her eyes were light blue and could be quite icy at times; her eyelashes were long, her eyebrows perfectly marked and her fine hair was always neatly coiled about her head. She was constantly letting everyone know even those in the household who were very well aware of it that she had not been brought up to live as she did, and it was only due to ‘circumstances’ that we were obliged to do so now.

Aunt Sophie was my mother’s elder sister. I think it was two years which separated them. She was of medium height, but plump, which made her look shorter; she had a round rosy face and little sharp brown eyes which looked rather like currants, and when she laughed they almost disappeared: it was a rather loud laugh which my mother said ‘grated’ on her nerves.

It was small wonder that they kept apart. On the rare occasions when my mother spoke of her, she invariably said that it was amazing that they had been brought up together.

We lived in what is known as ‘genteel poverty’ my mother, myself and two maids: Meg, a relic from those ‘better days’, and Amy, who was in her early teens, a Middlemore girl, from one of the cottages on the other side of the Common.

My mother was much occupied with keeping up appearances She had been brought up at Cedar Hall and I always thought it was unfortunate that this mansion was close enough to be perpetually in view.

There it stood, in all its grandeur, which seemed the greater when compared with Lavender House, our humble abode. Cedar Hall was the house in Middlemore. Church fetes were held on its lawn and one of its rooms was always made available for ecclesiastical meetings when necessary; and the carol singers assembled in the courtyard every Christmas Eve for mulled wine and mince pies when they gave their performance. There were many servants and it dominated the village.

My mother had two tragedies to suffer. Not only had she lost her old home, which had had to be sold when her father died and the extent of his debts had been revealed, but it had been bought by the Carters, who had amassed a fortune from selling sweets and tobacco in every town in England. They were undesirable on two counts they were vulgar and they were rich.

Every time she looked in the direction of Cedar Hall, my mother’s face would harden and her lips tighten, and the deep anger she felt was obvious; and of course that happened when she looked out of her bedroom window. We were all accustomed to the daily lament. It dominated our lives as well as hers.

Meg said: “It would have been better if we’d got right away. Looking at the old place all day don’t help much.”

One day I said to my mother: “Why don’t we move away? Somewhere where you don’t have to look at it all the time.”

I saw the horror in her face and, young as I was, I thought: She wants to be there. She couldn’t bear not to be. I could not understand then but I did later that she enjoyed her misery and resentment.

She wanted to continue as she had in the old days in Cedar Hall. She liked to participate in church matters taking a leading part in organizing bazaars and that sort of thing. It irritated her that the summer fete could not be held on our lawn.

Meg laughed at that and commented to Amy: “What! On six feet of grass!

Don’t make me laugh! “

There was a governess for me. In our position it was essential, said my mother. She could not afford to send me away to school and the idea of my attending the one in the village was quite out of the question.

There was only one alternative, so the governesses came. They did not stay long. References to past grandeur were no substitute for the lack of it in Lavender House. It had been Cottage when we came, Meg told me.

“Yes, for years it was Lavender Cottage, and painting ” House” over ” Cottage” did nothing more than that.”

My mother was not a very communicative person and although I heard a great deal about the glories of the past, she said very little about the subject which interested me most: that of my father.

When I asked her about him her lips tightened and she seemed more like a statue than ever just as I saw her look when she spoke of the Carters of Cedar Hall.

She said: “You have no father … now.”

There was something significant about the ‘now’ and the pause before it, so I protested: “But I had once.”

“Don’t be absurd, Frederica. Of course everyone had a father once.”

I had been called Frederica because there had been many Fredericks in the family of Cedar Hall. My mother had told me that there were six of them in the picture gallery there. I had heard of Sir Frederick, knighted on Bosworth Field; one who had distinguished himself at Waterloo; and another who had shone in the Royalist cause during the Civil War. Had I been a boy, I should have been Frederick. As it was, I must be Frederica, which I found inconvenient and inclined to be shortened to Freddie or even Fred, which had on more than one occasion led to obvious confusion.

“Did he die?” I asked.

“I have told you. You have no father now. That is an end of the matter.”

After that I knew there was some secret about him.

I did not remember ever seeing him. In fact, I could not remember living anywhere but in this house. The Common, the cottages, the church, all in the shadow of Cedar Hall, were part of my life till then.

I spent a great deal of time in the kitchen with Meg and Amy. They were more friendly than anyone else.

I was not allowed to make friends with the village people and as far as the Carters up at the hall were concerned, my mother was distantly polite with them.

I soon learned that my mother was a very unhappy woman. Now that I was getting older, Meg used to talk to me a good deal.

This life,” she said on one occasion, ‘is no life at all. Lavender House, my foot. Everyone knows it was Lavender Cottage. You can’t make a house grand by changing its name. I’ll tell you what. Miss Fred .. ” Although I was Miss Frederica in my mother’s hearing, when we were alone-Meg and I — I was plain Miss Fred or sometimes Miss Freddie.

Frederica, being one of those ‘outlandish’ names which Meg did not think much of, she could not be expected to use it more than was necessary.

“I’ll tell you what. Miss Fred. A spade’s a spade, no matter what fancy name you give it, and I reckon we’d be better off in a nice little house in Clapham … being just what we was and not what we’re pretending to be. There’d have been a little bit of life up there, too.”

Meg’s eyes were misty with longing. She had been brought up in the East End of London and was proud of it.

“A bit of life, there was up there, Saturday night in the markets with all them flares on the stalls. Cockles and mussels, winkles and whelks and jellied eels. What a treat, eh? And what is there here? Tell me that.”

“There’s the fete and the choral society.”

“Don’t make me laugh! A lot of stuck-ups trying to pretend they’re what they’re not. Give me London.”

Meg liked to talk of the great city. The horse buses that could take you right up to the West End. She’d been up there at Jubilee time.

That was something. Only a nipper she was then, before she’d been such an idiot and settled for a job in the country . that was before she’d worked at Cedar Hall. Seen the Queen in her carriage, she had.

Not all that to look at, but a Queen she was . and she’d let you know it.

“Yes, we could have lived up there instead of being down here. A nice little place. Bromley by Bow, perhaps. Stepney. You could have got something dirt cheap there. But we had to come here. Lavender House. Why, even the lavender’s no better than that we used to grow in our garden in Stepney. “

When Meg yearned for London life she would enlighten me considerably.

“You’ve been with my mother a long time, Meg,” I said.

“All of fifteen years.”

“And you would have known my father.”

She was looking back to the London markets and jellied eels on a Saturday night. She drew herself away from that delectable scene with reluctance.

“He was a one,” she said, and started to laugh.

“What sort of a one, Meg?” I said.

“Well, never you mind!” Her lips turned up at the corners and I could see that she was amused. It must have been due to memories of my father.

“I could have told her, I could.”

“What could you have told?”

“It couldn’t have lasted. I said to the cook we had a cook in those days, a bit of a tartar she was and I was nothing much, kitchen maid, that was me. I said to her, ” It won’t last. He’s not the sort to settle and she’s not the sort to put up with much. “

“What did she have to put up with?”

“Him, of course. And he had to put up with her. I said to Cook, ” That won’t work,” and I was right!”

“I don’t remember him.”

“You wouldn’t have been much more than a year old when he went.”

“Where did he go?”

“With her, I suppose … the other one.”

“Don’t you think it’s time I knew?”

“I reckon you’ll know when it is.”

I knew that that morning there had been a coolness between Meg and my mother, who had said the beef was touch. Meg had retorted that if we didn’t have the best beef it was likely to be tough, to which my mother had replied that it should have been cooked a little longer. Meg was on the point of giving notice, which was her strongest weapon in these conflicts. Where would we get another Meg? It was good to have someone who had been in the family for years. As for Meg, I guessed she did not want the bother of moving. It was a threat to be used in moments of crisis: and neither of them could be sure that, if driven to extremity, the other might not take action, and either one could find herself in a position from which it would be undignified to retreat.

The trouble had been smoothed over, but Meg was still resentful; and at such times it was easier to extract information from her.

“Do you know, I’m nearly thirteen years old, Meg?” I said.

“Of course I know it.”

“I reckon I’m old enough.”

“You’ve got a sharp head on your shoulders. Miss Fred. I will say that for you. And you don’t take after her.”

I knew Meg had a certain tenderness for me. I had heard her refer to me when talking to Amy as ‘that poor mite’.

“I think I ought to know about my father,” I went on.

“Fathers,” she said, lapsing into her own past, which was a habit with her.

“They can be funny things. You get the doting sort and there’s some who are ready with the strap at the flicker of an eyelid. I had one of them. Say a word he thought out of place and he’d be unstrapping his belt and you’d be in for it. Saturday nights … well, he was fond of the liquor, he was, and when he was rolling drunk you kept out of his way. There’s fathers for you.”

“That must have been awful, Meg. Tell me about mine.”

“He was very good-looking. I will say that for him. They was a handsome pair. They used to go to these regimental balls. They’d look a picture, the two of them together.

Your mother hadn’t got that sour look then well, not all the time.

"Seven for a Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Seven for a Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Seven for a Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.