She grimaced.

“Do you know, after the way he retrieved my hat, I thought we were going to have some fun with him.”

“Perhaps we shall.”

“I had no idea,” she said.

“I thought he was just an ordinary man. I think I shall call him St. Luke.”

“That seems, shall we say, a little blasphemous.”

“But a missionary!” she murmured under her breath.

She was disappointed.

The days were passing. We had slipped into a routine and one day was very like another until we came into port; and then there would be times of activity during which we would be absorbed by new impressions in a world that seemed very far away from Harper’s Green.

My friendship with Luke Armour was growing. He was charming and a diverting companion. He told amusing stories of the places he had visited and rarely spoke, unless pressed, of his dedicated calling. He told me once that when people discovered it they were inclined to change towards him, sometimes avoiding him, at others expecting him to preach to them. He had noticed that Mrs. Marchmont’s attitude seemed different since she had known.

Tamarisk had certainly been a little taken aback. She had been so delighted by the manner in which he had rescued her hat from the ape. She had said to me that it was an interesting way to begin a friendship and she had thought there might be fun in developing the acquaintance, particularly as he was going to Casker’s Island. I was amazed that, after her recent experiences, she could contemplate a somewhat flirtatious relationship, for I was sure she was wondering how there could be such with a missionary.

I thought then: All that has happened to her has not changed her.

The Dunstans left us at Bombay. We said goodbye to them with some regrets on both sides, I think. They had been good friends to us and helped us considerably by initiating us into the ways of shipboard life.

After they left Tamarisk and I went ashore with a party of acquaintances. We were struck by the beauty of many of the buildings and appalled by the poverty we witnessed. There were beggars everywhere. We wanted to give but it was beyond our means to help all those who crowded around us; and I felt I should be haunted for a long time by those pleading dark eyes. The women in their beautifully coloured saris and the well-dressed men seemed indifferent to the plight of the beggars; and the contrast between wealth and poverty was both distressing and depressing.

We had an adventure in Bombay which might have been disastrous. The Dunstans had impressed on us that it was always unwise to go ashore without ship companions and we should never go alone. We were passing with our party through narrow streets in which stalls had been set up.

Such places always caught the attention of Tamarisk. I must say the goods looked intriguing. There were displays of silver articles and said lengths beautifully embroidered, trinkets and all kinds of leather items.

Tamarisk was interested in some silver bangles.

She picked some up and tried them on and after that decided she must have them. There was some difficulty about the money and by the time the transaction was completed we found that the rest of the party were out of sight.

I seized Tamarisk’s arm and cried: “The others have gone. We must find them at once.”

“Why?” said Tamarisk.

“We can get some conveyance to take us back to the ship just as easily as they can.”

We started along the streets. We had been with a Mrs. Jennings who had once lived in Bombay and knew the place well. She had taken charge of us all; and now that we had lost sight of the party, I could not help feeling apprehensive.

There were crowds everywhere and it was not easy to make our way through the press of people. When we reached the end of the street I could not see any of our party. I looked round in dismay, for nor was there any sign of a vehicle which might take us back to the ship.

A small boy ran into me. I was startled. Another dashed by. When they had disappeared, I saw that the small bag in which I was carrying our money was no longer on my arm.

I cried: “They have stolen our money. Look at the time! The ship will leave in just over an hour and we were asked to be on board half an hour before she sailed.”

We were both panic-stricken now. We were in an unknown country with no money; we were some way from the ship and had no idea how to get back to it.

I asked one or two people the way to the dock. They looked at me blankly. They had no idea what I was talking about. Desperately I searched for a European face.

Possibilities flashed into my mind. What should we do? We were in a desperate situation and all because we had been absorbed in Tamarisk’s purchase.

We went up another street. There was a wider road ahead of us.

I said: “We have to try this.”

“We didn’t come this way,” replied Tamarisk.

“There must be someone who can tell us the way to the docks.”

And just at that moment I saw him.

I cried out: “Mr. Armour!”

He came hurrying towards us.

“I met Mrs. Jennings,” he said.

“She told me you’d strayed in the market there. I said I’d come and look for you.”

“We lost our money,” said Tamarisk in great relief.

“Some horrid boys stole it.”

“It’s unwise to be on your own.”

“Oh, how glad I am to see you!” cried Tamarisk.

“Aren’t you, Fred?”

“I can’t tell you how glad! I was getting more and more terrified every moment.”

“Afraid we’d sail without you? Which would have happened, of course.”

“You are our saviour, Mr. Armour,” said Tamarisk. She took his arm and smiled up at him.

“Now you will get us back to the ship, I know.”

He said: “We shall have to walk a little and then we can get a ride.

There’s nothing just here. But we are not so very far from the docks.”

My relief was immense. The prospect of being left alone in this place had daunted us both; and now here was our rescuer suddenly coming upon us with the news that he had come to look for us.

“How did you find us so soon?” asked Tamarisk.

“Mrs. Jennings said they had lost you in the market. I knew the place and guessed you’d come out where you did from Mrs. Jennings’s description. I thought it best to hang about there for a few minutes.

And you see, it worked. “

“It is the second time you have come to my aid,” Tamarisk reminded him.

“First the hat and now this. I shall expect you to be at hand at the next time of danger.”

“I hope I shall always be at hand to help you when you need me,” he said.

I was almost happy as we mounted the gangway and stepped on board. It had been a miraculous rescue and I still shivered to contemplate the alternative. I was glad, too, that it was Luke Armour who had saved us. I was liking him more and more.

So was Tamarisk, although she still referred to him as St. Luke.

She had certainly changed towards him. On one or two occasions I found her sitting on deck with him. I usually joined them and we would have a pleasant time together.

We were getting near to the time when we should leave the ship and Tamarisk admitted that she was glad we should not be the only ones going to Casker’s Island, and that it would be good to have St. Luke there. He was resourceful and would be of great help.

She told me that he had even talked to her about what he was going to do on Casker’s Island. He had no idea what he would find there, but he believed it would be different from any other place he had known. The mission was in its infancy and the initial stage was always the most difficult. They had to make the people understand that what was being done was in their interest and not for the sake of interference.

“He’s an unusual man,” said Tamarisk to me.

“I never knew anyone like him. He is very frank and honest. I told him about myself, how I had been infatuated with Gaston … about my marriage … and everything … even how Gaston had been found dead. He listened with great attention.”

“I suppose,” I said, ‘it is a story which would attract most people’s attention. “

“He seemed to understand how I felt that frightful not knowing and wondering who … and also being under suspicion myself. He said the police could not have suspected me, or they would not have let me leave the country. I told him that it had seemed as though we were all cleared myself, my brother and the man whose daughter he had seduced, everybody. That was what made it so difficult for us all, not knowing. I said that I thought it was someone from Gaston’s past, someone who had had a grudge against him. He promised he would pray for me, and I replied that I had prayed for myself without much effect, but perhaps he would be listened to more than I would, being on better terms with those above. He was a bit withdrawn after that.”

“You shouldn’t have said it.”

“I knew afterwards, but I meant it in a way. He is such a good person and I suppose it is logical to suppose he would get a hearing more easily than someone like me. If there is any justice he would. He’s the sort of person whose prayers ought to be answered and I reckon he prays as much for others as he does for himself. He’s a nice man, our St. Luke. I really like him.”

We were sailing up the Australian coast first Free-mantle, then Adelaide, Melbourne, and that brought us very near to our departure from the Queen of the South.

At last we reached that splendid harbour which Captain Cook had said was one of the finest in the world. It was magnificent, passing through the Heads, to see that town which not very long before had been merely a settlement, stretching out before us.

There was little time for us to see much, for the bustle of approaching departure prevailed throughout the ship. There were goodbyes to be said to the people whom we had sailed with all those weeks, with whom we had sat down to meals three times a day. I said to Tamarisk: “We do not see our close friends at home as often as that.”

And now they were going out of our lives for ever and most of them would become just a memory.

Luke Armour had become very businesslike. He wanted to make sure that all our luggage was conveyed to the Golden Dawn and that we should all go aboard together.

It was a pity we could not see more of Sydney a very fine city, we realized from what little we could observe. However, the most important thing to us was to proceed satisfactorily on our journey.

“How very efficient our holy man is!” said Tamarisk. There was always a note of mockery in her voice when she talked of Luke. She liked him; it was just that she could not regard a man who followed his calling as being like other men.

At last we had boarded the Golden Dawn and were on our way. She was a cargo ship first and foremost, and it was only occasionally that she carried passengers.

We had a rough crossing of the Tasman Sea when we spent most of our time in bed before we reached Welling ton. Our stay there was brief, as it depended on the amount of goods to be taken on and off. Then we were on our way to Cato Cato.

There followed a leisurely day at sea. The weather was calm and hot and it was a great pleasure to sit on deck and look out on a smooth and pellucid sea in which one glimpsed here and there flying fishes rising gracefully from the water and now and then a shoal of dolphins at play.

We sat on deck with Luke and learned of his childhood which had been spent in London. His father was a business man who had done well in financial circles. He wanted both Luke and his elder brother to join the business but Luke had had other ideas. On his father’s death, he had been left sufficient money to follow his inclination and the elder brother had taken over the business.

Luke had not liked his father’s business but he admitted that it enabled him to do what he wanted with his life. As his brother had complied with their father’s wishes, he felt he could go his own way with a clear conscience.

“So,” said Tamarisk teasingly, which was typical of her manner to Luke, ‘you do not like your father’s business, but you admit that because of it you can spend your time doing what you want. How does that suit your conscience? “

“I see your point,” he said with a smile.

“But I believe in life one must apply simple logic. My income, which enables me to work as I want, comes to me through a business in which I do not wish to work.

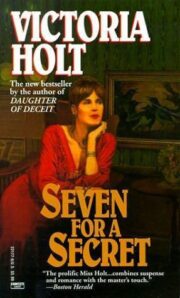

"Seven for a Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Seven for a Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Seven for a Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.