Her hair was going grey and she had an anxious expression which looked as though it might be perpetual. She was neatly dressed in a grey blouse and skirt.

“I’ve brought Frederica Hammond to see you,” said Tamarisk.

“Oh, that’s nice,” said Lucy Lane.

“Come in.”

We went into a small hall and through to a small, neat, highly polished sitting-room.

“So you’re the new pupil up at the House,” said Miss Lucy Lane to me.

“Miss Cardingham’s niece.”

“Yes,” I replied.

“And taking lessons with Miss Tamarisk. That’s nice.”

We sat down.

“And how is Flora today?” asked Tamarisk, who was disappointed because she wasn’t there for me to see.

“She’s in her room. I won’t disturb her. And how are you liking Harper’s Green, miss?”

“It’s very pleasant,” I told her.

“And your poor mama … she’s ill, I understand.”

I said that was so and half-expected her to say “That’s nice.” But she said unexpectedly: “Oh … life can be hard.” Tamarisk was getting bored.

“I was wondering if we could say hello to Flora,” she said.

Lucy Lane looked dismayed. I was sure she was preparing to say this was not possible when, to her dismay, and Tamarisk’s delight, the door opened and a woman stood on the threshold of the room.

There was a faint resemblance to Lucy and I knew this must be Flora; but where Lucy had a look of extreme alertness. Flora’s large bewildered eyes gave the impression she was trying to see something which was beyond her vision. In her arms she carried a doll. There was something very disturbing about a middle-aged woman carrying a doll in such a way.

“Hello, Flora,” said Tamarisk.

“I’ve come to see you and this is Fred Hammond. She’s a girl but with a name like that you might not think so.” She giggled a little.

I said: “My name is Frederica. Frederica Hammond.”

Flora nodded, looking from Tamarisk to me.

“Fred has lessons with us,” went on Tamarisk.

“Would you like to go back to your room. Flora?” asked Lucy anxiously.

Flora shook her head. She looked down at the doll.

“He’s fretful today,” she said.

“Teething.”

“It’s a little boy, is it?” said Tamarisk.

Flora sat down, laying the doll on her lap. She gazed down at it tenderly.

“Isn’t it time he had his nap?” asked Lucy.

“Come. Let’s go up. Excuse me,” she said to us.

And laying her hand firmly on Flora’s arm, she led her away.

Tamarisk looked at me and tapped the side of her head.

“I told you so,” she whispered.

“She’s batty. Lucy tries to make out she’s not so bad … but she really is off her head.”

“Poor woman!” I said.

“It must be sad for them both. I think we ought to go. They don’t want us here. We shouldn’t have come.”

“All right,” said Tamarisk.

“I just wanted you to see Flora.”

“We’ll have to wait until Lucy comes back and then we’ll leave.”

Which was what we did.

As we walked away. Tamarisk said: “What did you think?”

“It’s very sad. The elder sister she is the elder, isn’t she Lucy, I mean?” Tamarisk nodded.

“She is really worried about the mad one.

How awful really, to believe that doll is a baby. “

“She thinks it is Crispin … only Crispin when he was a baby!”

“I wonder what made her go like that?”

“I never thought of that. It’s years and years since Crispin was a baby, and after Flora went funny, Lucy took him over he was still only a baby then. Then he went away to school when he was about nine.

He always liked old Lucy. Her father used to be one of the gardeners and they had the cottage because of that. He died before Lucy came back here. First of all she was working somewhere in the North. Their mother stayed in the cottage when the father died and Lucy came back.

Well, that’s what I’ve heard and soon after that Flora went batty and Lucy became Crispin’s nurse. “

“It is good of Crispin to let them stay in the cottage now neither of them work for St. Aubyn’s.”

“He likes Lucy. I told you, she was his nanny and most j people are like that about their nannies.”

As we walked back I could not stop thinking about the strange woman and her doll which she thought was the baby Crispin.

It was hard to think of that arrogant man as a baby.

In Barrow Wood

My fellow pupils had been to tea at The Rowans and at St. Aubyn’s. Then we were invited to the Bell House. Tamarisk found an excuse for being unable to go and consequently I was the only guest.

When I entered the front garden I felt a twinge of uneasiness. I passed the wooden seat where I had sat that day when I was waiting for Rachel, and her uncle had talked to me. I hoped he would not be there today.

I rang the bell and a maid opened the door.

“You’re the young lady for Miss Rachel,” she said.

“Come in.”

I was taken through the hall to a room with mullioned windows which looked out on a lawn. The curtains were thick and dark, shutting out much of the light. I immediately noticed the picture of the Crucifixion on the wall. It shocked me because it was so realistic. I could distinctly see the nails in the hands and feet and the red blood which dripped from them. It horrified me and I could not bear to look at it. There was another picture, of a saint, I presumed, because there was a halo above his head: he was pierced with arrows. There was yet another of a man tied to a stake. He was standing in water and I realized that his fate would be to drown slowly as the tide rose. The cruelty of men seemed to be the theme of all these pictures. They made me shudder. It occurred to me that this room had been made dark and sombre by Mr. Dorian.

Rachel came in. Her face lit up at the sight of me.

“I’m glad Tamarisk didn’t come,” she said.

“She makes fun of everything.”

“You don’t want to take any notice of her,” I said.

“I don’t want to but I do,” replied Rachel.

“We’re going to have tea here. My aunt is coming to meet you.”

Not the uncle, I hoped.

Rachel’s Aunt Hilda came in then. She was tall and rather angular. Her hair was drawn back tightly from her face which ought to have made her look severe, but it did not. She looked apprehensive, vulnerable. She was very different from the uncle who looked so sure that he was always right and so good.

“Aunt Hilda,” said Rachel, ‘this is Frederica. “

“How are you?” said Aunt Hilda, taking my hand in her cold one.

“Rachel tells me you and she have become good friends. It is good of you to come and visit us. We’ll have tea now.”

It was brought by the maid who had let me in. There was bread and butter, scones and seed cake.

“We always say grace before any meal in this house,” Aunt Hilda told me. She spoke as though she were repeating a lesson.

The grace was long, expressing the gratitude of miserable sinners for benefits received.

When she had served tea. Aunt Hilda asked me questions about my mother and how I was fitting into life in Harper’s Green.

It was rather dull compared with tea at St. Aubyn’s. I wished that Tamarisk had been with us, for, although she could be quite rude at times, at least she was lively.

To my dismay, just as we were finishing tea, Mr. Dorian came in.

He surveyed us with interest and I was aware that his eyes rested on me.

“Ah,” he said.

“A tea-party.”

I thought Aunt Hilda looked a little guilty, as though she were caught indulging in some bacchanalian feast; but he was not angry. He stood rubbing his hands together. They must have been very dry because they made a faint rasping noise which I found repulsive. He continued to look at me.

“I suppose you are just about the same age as my niece,” he said.

“I am thirteen.”

“A child still. On the threshold of life. You will find that life is full of pitfalls, my dear. You will have to be on guard against the Devil and all his wiles.”

We had left the table and I was seated on a sofa. He took a place beside me and moved close to me.

“Do you say your prayers every night, my dear?” he asked.

“Weller …”

He wagged a finger at me and lightly touched my cheek. I shrank away from him, but he did not seem to be aware of this. His eyes were very bright.

He went on: “You kneel by your bed … in your nightgown.” The tip of his tongue protruded slightly and touched his upper lip before it disappeared.

“And you pray to God to forgive you for the sins you have committed during the day. You are young, but the young can be sinful.

Remember that you could be carried off to face your Maker at any moment.

“In the midst of life we are in death.” You yes, even you, my child could be carried off with all your sins upon you to face your Maker.”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” I said, trying to move away from him without appearing to do so.

“No, indeed no. So … every night, you must kneel by your bed in your nightgown, and pray that all the naughty things you have done during the day or even thought may be forgiven.”

I shivered. Tamarisk would have been able to laugh at all this. I would have caught her eye and she would have made one of her grimaces. She would say the man was ‘batty’ as batty as poor Flora Lane, but in a different way. He just went on about sins and Flora thought a doll was a baby, that was all.

But I had a great desire to get out of this house and I hoped I would never come into it again. I did not under stand why this man frightened me so much but there was no doubt that he did.

I said to Aunt Hilda: “Thank you so much for asking me. My aunt will be expecting me back and I think I should go now.”

It sounded feeble. Aunt Sophie knew where I was and she would not be expecting me yet. But I had to get out of this house.

Aunt Hilda, who had looked uncomfortable while her husband was talking, seemed almost relieved.

“Well then, we mustn’t detain you, dear,” she said.

“It was so nice of you to come. Rachel, will you take your guest to the gate?”

Rachel rose with alacrity.

“Goodbye,” I said, trying not to look at Mr. Dorian.

It was a relief to escape. I wanted to run. I had a sudden fear that Mr. Dorian might follow me and go on talking about my sins, while he kept looking at me in that odd way.

Rachel came to the gate with me.

“I hope it was all right,” she said.

“Oh yes … yes,” I lied.

“It was a pity …” She did not continue but I knew what she meant.

If Mr. Dorian had not come in it would have been an ordinary tea-party.

I did say: “Does he always talk like that … about sin and everything?”

“Well, he’s very good, you see. He goes to church three times on Sunday, though he does not like the Reverend Hetherington very much. He says he leans towards Popery.”

“I think he believes everyone is full of sin.”

“That is how good people are.”

“I’d rather have someone not so good. It must be uncomfortable.” I paused. I was saying too much. After all, Rachel had to live in the house with him.

At the gate I looked back at the house. I had the uncanny feeling that he might be watching me from one of the windows and I just wanted to run as fast as I could to put a great distance between that house and myself.

“Goodbye, Rachel,” I said and started off.

It was good to feel the wind on my face. I thought: He’d never be able to run as fast as I can. He’d never catch me if he tried.

I did not take the straight path home. That man had made such an impression on me, I wanted to wash it completely out of my mind but I could not. The memory of him remained. His dry hands that rasped when he rubbed them together, his intent eyes with the light lashes that were hardly perceptible, the way in which he moistened his lips when he looked at me. They aroused alarm in me.

How could Rachel live in the same house with such a man? But he was her uncle. She had to. I thought, as I had a hundred times before, how lucky I was to have come to Aunt Sophie.

Running into the wind seemed to wash away the vague unpleasantness.

This was a strange place . fascinating in a way. One had the impression that weird things could happen here. There was Flora Lane with her doll, and Mr. Dorian with . what was it? I could not say.

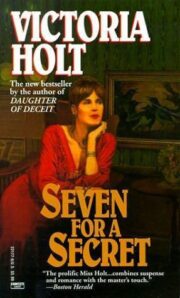

"Seven for a Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Seven for a Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Seven for a Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.