Chick Martin was a guy’s guy. There were always other men around the house at night and on the weekends-other attorneys and executives and business owners who played golf with Chick, or who accepted tickets to the Eagles, or who came over to the house on the last Thursday of every month for poker. Poker in the Martin household was a sacred affair that occurred in the game room and involved cigar smoking and subs delivered from Minella’s Diner. On poker nights, Meredith’s mother read in her bedroom with the door closed, and Meredith was supposed to do her homework upstairs and go straight to bed. Meredith always broke this rule. She wandered down to the game room, and her father would let her sit on his lap and munch on the dill pickle that accompanied his eggplant parm sub, while he played his hand. When she got older, he pulled up a chair for her and taught her how to read the cards.

The other men accepted Meredith’s presence in the room, though she could tell they didn’t love it, so she never stayed for more than three hands, and she never asked to play.

Once, when she was just out of the room, the door closing behind her, she heard Mr. Lewis, who was an estate attorney for Blank, Rome, say, “That’s a good-looking daughter you got there, Chick.”

And Meredith’s father said, “Watch your mouth.”

And George Wayne, who was a big shot at PSFS and a descendant of General Anthony Wayne, said, “Do you ever wish you’d had a boy, Chickie?”

And Meredith’s father said, “Hell, no. I wouldn’t trade Meredith in for a hundred boys. That girl is perfection. That girl owns my heart.”

Hearing her father speak those words confirmed what Meredith already knew: she was safe. Her father’s love was both a cocoon and a rabbit’s foot. She would live a happy life.

And, indeed, she did. Her grades were excellent, and she was a natural athlete: she played field hockey and lacrosse, and she was a champion diver. As a diver, she made it to the finals in State College her junior and senior years; in her senior year, she placed third. She’d had interest from Big Ten schools, but she didn’t want to carry the burden that a Division I athletic scholarship entailed. She wanted to be well rounded. She edited the yearbook and was a lector during morning chapel. She was that girl at Merion Mercy, the girl everyone admired and talked about with near-embarrassing praise.

Meredith was safe, too, because she’d had a best friend since the beginning of time, and that friend was Constance O’Brien. They met at preschool at Tarleton, although Meredith didn’t actually remember meeting Connie. By the time their synapses connected time and circumstance in a meaningful way, they had already been friends for years, and so it seemed to both girls that they had always been together. They grew up a half mile from each other in the same kind of house, which is to say, Catholic, upper-middle class, civilized but not snobbish. The only difference between the two homes was that Connie’s mother, Veronica, drank. And the way Meredith knew that Veronica O’Brien drank was because her own parents talked about it: Veronica went to the Mastersons’ party, picked a fight with her husband, Bill, and battled it out with him on the front lawn. Veronica fell down and bruised her hip. She forgot to pay the neighborhood babysitter so many times that the babysitter refused to work there anymore. When Meredith was older, she heard about Veronica O’Brien’s drinking from Connie. Her mother left a bottle of vodka in the second fridge in the garage and did three shots before Bill O’Brien came home from work. Veronica committed minor offenses like throwing away Connie’s paper on Mark Twain, and major offenses like setting the kitchen drapes on fire. Connie and Toby had learned to keep their friends out of the house. But they took advantage of the money and the freedom their mother bestowed on them while drinking, and when they reached a certain age, they burgled their mother’s wine and vodka and gin and drank it themselves.

Veronica O’Brien’s drinking-though it did manifest itself in more insidious ways eventually-did little to hamper Meredith and Connie’s childhood happiness together. They were twins, sisters, soul mates. As they got older, however, the peace was harder to keep. They were growing and changing; things grew nuanced. There was one twenty-four-hour period when Meredith and Connie didn’t speak. This was right after Meredith told Connie that she, Meredith, had kissed Connie’s brother, Toby, on the way home from Wendy Thurber’s late-night pool party.

Meredith had dutifully reported every detail to Connie by 8 a.m., just as she would have if Toby had been any other boy-but this time, Connie was disgusted. Meredith and Toby? It was appalling.

Meredith had felt ashamed and confused. She had expected Connie to be happy. But Connie slammed the phone down on Meredith, and when Meredith called back, the phone rang and rang. Meredith kept calling until Veronica answered and pleasantly and soberly explained that Connie didn’t want to talk right that second. Meredith should call back later, after Connie had had a chance to calm down.

Meredith was stunned. She hung up the phone and looked out her bedroom window down the street toward Connie’s house. She would forfeit Toby, then. She would give him up. It wasn’t worth ruining her friendship with Connie.

But here, Meredith faltered. She was a hostage to her feelings and, stronger still, her hormones. She had known Toby O’Brien just as long as she had known Connie, essentially her entire life. They had thrown water balloons at each other in the O’Briens’ backyard on hot afternoons, and they had watched horror movies side by side in the O’Briens’ shag-carpeted den, eating Jiffy Pop and Jax cheese doodles. Whenever they went somewhere in the O’Briens’ Ford Country Squire-to Shakey’s for pizza or to the King of Prussia Mall or downtown to Wanamaker’s to see the light show at Christmas-Connie, Meredith, and Toby had sat three across in the backseat, and sometimes Meredith’s and Toby’s knees had knocked, but it had never meant a thing.

How to explain what happened? It was like a switch had flipped and in an instant the world had changed, there in the deep end of Wendy Thurber’s pool. There had been a bunch of kids at the party-Wendy, Wendy’s brother Hank, Matt Klein, whom Connie was dating (though secretly, because Matt was Jewish and Connie feared her parents would object), Connie, Toby, Meredith, a girl from the field-hockey team named Nadine Dexter, who was chunky and a little butch, and Wendy’s runty next-door neighbor Caleb Burns. There was the usual splashing and roughhousing and dunking; all of the kids were in the pool except for Connie, who claimed the water was too cold. She lounged in a chaise wearing her petal-pink Lilly Pulitzer cover-up, and she braided and rebraided her strawberry-blond hair. Meredith impressed everyone with her dives. She had just perfected her front one and half somersault with one and half twists, which was a crowd pleaser.

As the party was starting to wind down, Meredith encountered Toby in the deep end. He had, as a joke, pulled at the string of her bikini top, the top had come loose, and her newly formed breasts-so new they were tender to the touch-were set free, bobbing for a second in the chlorinated water. Meredith yelped and struggled to retie her top while treading water. Toby laughed wickedly. He swam up behind her and grabbed her, and she could feel his erection against her backside, though it took a second to figure out what was happening. Her mind was racing, reconciling what she had learned in health class, what she had read in Judy Blume novels, and the fact that Toby was a seventeen-year-old boy who might just be turned on by her newly formed breasts. Immediately, there was a surge of arousal. In that instant, Meredith became a sexual being. She felt momentarily sorry for her father and her mother, because she was lost to them forever. There was, she understood, no going back.

Connie left the party with Matt Klein. They were off to make out and push at the boundaries of Connie’s virginity, though Connie had said she was determined to stay chaste until her sixteenth birthday. Connie talked about her sex life all the time, and up to that point, Meredith had bobbed her head at what felt like the appropriate moments, not having a clue what Connie was talking about but not wanting to admit it. Now, suddenly, she got it. Desire.

She dried off and put her shorts and T-shirt back on, then a sweatshirt because it was nighttime and chilly. She took a chip off the snack table but refrained from the onion dip. Caleb Burns’s mother called out from next door that it was time for him to go home. Wendy’s brother Hank, who was friends with Toby, wanted Toby to stick around, hang out in his room, and listen to Led Zeppelin.

Toby was bare chested with a towel wrapped around his waist. Meredith was afraid to look at him too closely. She was dazzled by how he had suddenly become a different person.

Toby said, “Sorry, man. I have to head out.” He and Hank did some kind of complicated handshake that they had either learned from watching Good Times on channel 17 or from hanging out on South Street on the weekends. Meredith knew that Toby would walk home-his house was nearby, hers a half a mile farther-not an impossible walk but not convenient either, in the dark. Meredith’s parents had said, as always, Just call if you need a ride home. But if Meredith called for a ride, she would be missing a critical opportunity.

She said to Wendy and Nadine, who were both attacking the bowl of chips, “I’m going to go, too.”

“Really?” Wendy said. She sounded disappointed, but Meredith had expected this. Wendy was a bit of a hanger-on; she was constantly peering over the proverbial fence at Meredith and Connie’s friendship. “Where did Connie go?”

“Where do you think?” Nadine asked slyly. “She went to get it on with Matt.”

Wendy’s eyes widened and Meredith shrugged. Wendy had clearly not been introduced to her own sexuality yet, though Nadine had, in whatever form that had taken. (Another girl? Someone from the camp she went to in Michigan?)

Meredith kissed Wendy’s cheek like an adult leaving a cocktail party and said, “Thanks for having me.”

“You’re walking?” Wendy said, sounding worried. “My dad can probably drive you.”

“No, I’ll walk,” Meredith said.

“I can ask him.”

“I’m fine,” Meredith said. She hurried to the gate. Toby was strolling across the Thurbers’ front lawn. He hadn’t waited for her and she hadn’t gotten out before him. She wondered if she had been imagining his erection, or if she had been flattering herself that the desire had been aimed at her. But if not her, then who? Not pathetic Wendy, and certainly not Nadine with her blocky shoulders and faint mustache. Meredith waved to the other girls and took off down Robinhood Road, trying to seem nonchalant. All this posturing! She wished Toby was behind her. Now it would look like she was chasing him.

When they were three houses away from the Thurbers’ and four houses away from the O’Briens’, Toby turned around and pretended to be surprised to find Meredith behind him.

“Hey,” he called out in a kind of whisper.

She was at a loss for words. She waved. Her hair was damp and when she touched it, she could feel that it held comb marks. The streetlights were on, so there were pools of light followed by abysses of darkness. Across the street, a man walked a golden retriever. It was Frank diStefano, the roofer, a friend of Meredith’s father. Oh, boy. But he didn’t see her.

Toby stopped in one of the dark spots to wait for her. Her heart was tripping over itself like two left feet. She was excited, scared, nearly breathless. Something was going to happen between her and Toby O’Brien. But no, that wasn’t possible. Toby was unfathomably cool, a good student and a great athlete, and he was as beautiful as Connie. He had dated the most alluring girl at Radnor-Divinity Michaels-and they had had an end-of-the-year breakup that was as spectacular as a Broadway show, where Divinity threatened to kill herself, and the school counselors and the state police were called in. (There had been simultaneous rumors circulating about Toby and the young French teacher, Mademoiselle Esme, which Connie called “completely idiotic, and yet not beyond Toby.”) Earlier that summer, Toby had started “hanging out” with an Indian girl named Ravi, who was a junior at Bryn Mawr. Compared to those girls, what did Meredith have to offer? She was his kid sister’s best friend, a completely known quantity, a giant yawn.

And yet…?

Meredith walked along the strip of lawn between the street and the sidewalk, and her feet were coated with grass clippings. She had her flip-flops in her hand and she stopped to put them on, partly as a stall tactic. She kept walking. Toby was leaning up against a tree that was in the front yard of a house where, clearly, no one was home.

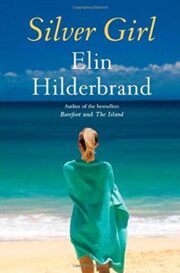

"Silver Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Silver Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Silver Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.