“It was not my chaplain, sir, who was driving down a narrow lane at what I do not scruple to call a shocking pace!” said Widmore, firing up.

“The place for a parson, I shall take leave to tell you, sir, is not on the box of a curricle, but in his pulpit!” retorted the General. “And now, if you will be good enough to retire, I may perhaps be allowed to transact the business which had brought me here!”

Mr. Whyteleafe, who had been staring at Hester with an expression on his face clearly indicative of the feelings of shock, dismay, and horror which had assailed him on seeing her thus, living, apparently, with her rejected suitor in a discreetly secluded spot, withdrew his gaze to direct an austere look at the General. The aspersion cast on his driving skill he disdained to notice, but he said, in a severe tone: “I venture to assert, sir, that the business which brings Lord Widmore and myself to call upon Sir Gareth Ludlow is sufficiently urgent to claim his instant attention. Moreover, I must remind you that our vehicle was the first to draw up at this hostelry!”

The General’s eyes started at him fiercely. “Ay! So it was, indeed! I am not very likely to forget it, Master Parson! Upon my soul, such effrontery I never before encountered!”

Lord Widmore, whose fretful nerves had by no means recovered from the shock of finding his curricle involved at the cross-road in a very minor collision with a post-chaise and four, began at once to prove to the General that no blame attached to his chaplain. As irritation always rendered him shrill, and the General’s voice retained much of its fine carrying quality, the ensuing altercation became noisy enough to cause Lady Hester to stiffen imperceptibly, and to lay one hand on the arm of Sir Gareth’s chair, as though for support. He was aware of her sudden tension, and covered her hand with his own, closing his fingers reassuringly round her wrist.

“Don’t be afraid! This is all sound and fury,” he said quietly.

She looked down at him, a smile wavering for a moment on her lips. “Oh, no! I am not afraid. It is only that I have a foolish dislike of loud, angry voices.”

“Yes, very disagreeable,” he agreed. “I must own, however, that I find this encounter excessively diverting. Kendal, do you care to wager any blunt on which of my engaging visitors first has private speech with me?”

The Captain, who had bent to catch these words, grinned, and said: “Oh, old Summercourt will bluster himself out, never fear! But who is the other fellow?”

“Lady Hester’s brother,” replied Sir Gareth. He added, his eyes on Lord Widmore: “Bent, if I know him, on queering my game and his own!”

“I beg pardon?” the Captain said, bending again to hear what had been uttered in an undertone.

“Nothing: I was talking to myself.”

Hester murmured: “Isn’t it odd that they should forget everything else, and quarrel about such a trifle?” She seemed to become aware of the clasp on her wrist, and tried to draw her hand away. The clasp tightened, and she abandoned the attempt, colouring faintly.

Mr. Whyteleafe, whose jealous eyes had not failed to mark the interlude, took a quick step forward, and commanded in a voice swelling with stern wrath: “Unhand her ladyship, sir!”

Hester blinked at him in surprise. Sir Gareth said, quite amiably “Go to the devil!”

The chaplain’s words, which had been spoken in a sharpened voice, recalled the heated disputants to matters of more moment than a grazed panel. The quarrel ceased abruptly; and the General, turning to glare at Sir Gareth, seemed suddenly to become aware of the lady standing beside his chair. His brows twitched together in a quelling frown; he demanded: “Who is this lady?”

“Never mind that,” said Lord Widmore, directing at Sir Gareth a look of mingled prohibition and entreaty.

Sir Gareth met it blandly, and turned his head towards the General. “This lady, sir, is the Lady Hester Theale. She has the misfortune to be Lord Widmore’s sister, and also to dislike heated altercations.”

His lordship’s angry but incoherent protest was overborne by the General’s more powerful voice. “Have I been led here on a fool’s errand?” he thundered. He rounded on Captain Kendal. “You young jackass, I told you to keep out of my affairs! I might have known you would lead me on a wild goose chase!”

Captain Kendal, quite undismayed by this ferocious attack, replied: “Yes, sir, in a way that’s what I have done. But all’s right, as I will explain to you, if you care to come in the house for a few minutes.”

A look of relief shot into the General’s eyes; in a far milder tone, he asked: “Neil, where is she?”

“Here, sir. I sent her upstairs to wash her face,” said the Captain.

“Here? With this—this—And you tell me all’s right?”

“I do, sir. You are very much obliged to Sir Gareth, as I shall show you.”

Before the General could reply, an interruption occurred. Amanda and Hildebrand, attracted by the sounds of the late altercation, had come out of the house, and had paused, surprised to find so many persons gathered around Sir Gareth. Amanda had washed away her tear stains, but she was looking unwontedly subdued. Hildebrand was carefully carrying a brimming glass of milk.

The General saw his granddaughter, and abandoned the rest of the company, going towards her with his hands held out. “Amanda! Oh, my pet, how could you do such a thing?”

She flew into his arms, crying that she was sorry, and would never, never do it again. The Captain, observing with satisfaction that his stern instructions were being obeyed, transferred his dispassionate gaze to the chaplain, who, upon recognizing Hildebrand, had flung out his arm, pointing a finger of doom at that astonished young gentleman, and ejaculating: “That is the rascal who lured Lady Hester to this place, my lord! Unhappy boy, you are found out! Do not seek to excuse yourself with lies, for they will not serve you!”

Hildebrand, who had been gazing at him with his mouth at half-cock, looked for guidance towards Sir Gareth, but before Sir Gareth could speak Mr. Whyteleafe warned him that it was useless to try to shelter behind his employer.

“Oh, Hildebrand, is that Uncle Gary’s milk?” said Hester. “What a good, remembering boy you are! But I quite thought I had given the glass to Amanda, which just shows what a dreadful memory I have!”

“Oh, you did, but she threw it away!” replied Hildebrand. “Here you are, sir: I’m sorry I have been such an age, but it went out of my head.”

“The only fault I have to find is that it ever re-entered your head,” said Sir Gareth. “Is this a moment for glasses of milk? Take it away!”

“No, pray don’t! Gareth, Dr. Chantry said that you were to drink a great deal of milk, and I won’t have you throw it away merely because all these absurd people are teasing you!” said Hester, taking the glass from Hildebrand. “And Sir Gareth is not Mr. Ross’s employer!” she informed the chaplain. “Of course, my brother-in-law isn’t his employer either, but never mind! It was quite my fault that he was obliged to be not perfectly truthful to you.”

“Lady Hester, I am appalled! I know not by what means you were brought to this place—”

“Hildebrand fetched me in a post-chaise. Now, Gareth!”

“You misunderstand me! Aware as I am, that Sir Gareth’s offer was repugnant to you, I cannot doubt that you were lured from Brancaster by some artifice. What arts—I shall not say threats!—have been used to compel your apparent complaisance today I may perhaps guess! But let me assure you—”

“That will do!” interrupted Sir Gareth, with an edge to his voice.

“Yes, but this is nothing but humdudgeon!” said Hildebrand. “I didn’t lure her! I just brought her here because Uncle Gary—Sir Gareth, I mean—needed her! She came to look after him, and we pretended she was his sister, so you may stop looking censoriously, which, though I don’t mean to be uncivil to a clergyman, is a great piece of impertinence! And as for threatening her, I should just like to see anyone try it, that’s all!”

“Oh, Hildebrand!” sighed Hester, overcome. “How very kind you are!”

“Good boy!” Sir Gareth said approvingly, handing him the empty glass. “Widmore, if you can contrive to come out of a state of what would appear to be a catalepsy, assemble the few wits God gave you, and attend to me, I trust I may be able to allay your brotherly anxiety!”

Lord Widmore, who, from the moment of Amanda’s arrival on the scene, had been standing in a spellbound condition, gave a start, and stammered: “How is this? Upon my soul! I do not know what to think! This goes beyond all bounds! That is the girl you had the effrontery to bring to Brancaster! So it was to take her to those relations of hers at Oundle, was it, that you went chasing after my uncle? Not that I believe it! I hope I am not such a gull!”

“That girl, sir,” said Captain Kendal, dropping a restraining hand on Sir Gareth’s shoulder, and keeping his penetrating eyes on Lord Widmore’s face, “is Miss Summercourt. She is shortly to become my wife, so if you have any further observations to make on this head, you may address them to me!”

“Widmore, do try not to be so silly!” begged Hester. “I can’t think how you can have so little commonsense! It is quite true that I came here to nurse Gareth, for he had had a very serious accident, and nearly died; but also I came to be a chaperon for Amanda—not that there was the least need of such a thing, when she was in Gareth’s charge, but although I have not a great deal of sense myself I do know that persons like you would think so. And I must say, Widmore, that it is very lowering to be so closely related to anyone with such a dreadfully commonplace mind as you have!”

He was so much taken aback by this unprecedented assault that he could find nothing to say. Amanda, who had poured the tale of her odyssey into her grandsire’s ears, seized the opportunity to address him. “Oh, Lord Widmore, pray excuse me for having been so uncivil as to run away with your uncle without taking leave of you and Lady Widmore and Lord Brancaster, or saying thank you for a very pleasant visit! And, please, Uncle Gary, forgive me for having been troublesome, and uncivil, and telling people you were abducting me, which Neil says you didn’t, though I must say it is abducting, when you force people to go with you. However, I am truly grateful to you for having been so kind, and letting me have Joseph. And Aunt Hester too. And now I have begged everybody’s pardon, except Hildebrand’s,” she continued, without the smallest pause, “so, please,Neil, don’t be vexed with me any more!”

“That’s a good girl,” said her betrothed, putting his arm round her, and giving her a slight hug.

“Amanda!” said the General sharply, as she rubbed her cheek against Captain Kendal’s arm. “Come here, child!”

The Captain released her, and her grandfather bade her run away and pack her boxes. She looked mutinous, but Captain Kendal endorsed the command, upon which she sighed, and went with lagging steps into the house.

“Now, sir!” said the General, turning to Sir Gareth. “I am satisfied that you have behaved like a man of honour to my granddaughter, and I will add that I am grateful to you for your care of her. But although I do not say that you are to blame for it, this has been a bad business—a very bad business! Should it become known that my granddaughter has been for nearly three weeks living under your protection, as I cannot doubt it will, since so many persons are aware of this circumstance, the damage to her reputation would be such as to—”

“Dear me, didn’t she tell you that I have been here all the time?” enquired Lady Hester.

“Ma’am,” said the General, “you were not with her at Kimbolton!”

“I beg pardon, sir,” put in Hildebrand diffidently, “but nobody saw her there but me, except the servants, of course, and they didn’t think anything but that she was Uncle Gary’s ward. Well, I thought she was, too!”

“What you thought, young man,” said the General crushingly, “isof no value! Be good enough not to interrupt me again! Ludlow, I am persuaded that I shall not find it necessary to urge you to adopt the only course open to a man of honour! You know the world: it has been impossible to keep my granddaughter’s disappearance from her home a secret from my neighbours. I am not so simple as to suppose that conjecture is not rife amongst them! Or, let me add, that your zeal in pursuing her sprang merely from altruistic motives! She is young, and I do not deny that she has some foolish fancies in her head, but I don’t doubt that a man of your address would very speedily succeed in engaging her affections.”

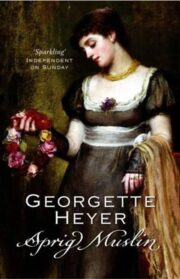

"Sprig Muslin" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sprig Muslin". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sprig Muslin" друзьям в соцсетях.