Kojima shook his head. “I’ve liked you all this time, Omachi. Didn’t I take you out on that date? Even if it didn’t go all that well.” His expression was earnest.

“So you’ve liked me all along?” I asked.

He gave a faint laugh. “I guess life is pretty funny that way.”

Kojima looked up at the moon for a moment. It was now enveloped by a thin haze.

Sensei, I thought to myself, and my next thought was Kojima.

“Thank you for tonight,” I said, staring at his jawline.

“What?”

“It was a lovely evening.”

The area below Kojima’s chin was much thicker than it had been when we were in high school. An accumulation of years. But this stoutness was not at all repugnant. In fact, I rather liked it. I tried to think of what Sensei’s jawline looked like. Surely, when Sensei had been the age that Kojima and I were now, his neck must have been appropriately thick. However, the ensuing years had whittled away any heft under his chin.

Kojima was looking at me, a bit surprised. The moon shone brightly, luminous even through the haze.

“So it’s not going to happen?” Kojima said, with an exaggerated sigh.

“Seems unlikely.”

“Aw, man… I’m just terrible on dates,” he laughed. I laughed with him.

“No, you’re not! You taught me how to swirl my wine and everything.”

“Yeah, I definitely shouldn’t do stuff like that.”

Kojima’s face was lit by the moonlight. I studied it now.

“Am I a good-looking guy?” he asked as he turned to face my gaze.

“Definitely, you’re very good-looking,” I answered gamely. Kojima pulled me by the hands up to standing.

“But not good-looking enough for it to happen?”

“You know, I’m a high school girl!”

“As if!” Kojima said, pouting. He too looked like a high school student when he made that face. He looked like a teenager who didn’t know the first thing about wine tasting.

We held hands and walked along the embankment. Kojima’s hand was warm in mine. The moonlight illuminated the cherry blossoms. I wondered where Sensei was at that moment.

“You know, I never really liked Ms. Ishino,” I told Kojima as we walked along.

“Really? Like I said before, I had a crush on her.”

“But you didn’t like Mr. Matsumoto.”

“Right, I thought he was stubborn and strict, you know?”

Little by little, we really were regressing to our high school days. The schoolyard looked white, bathed as it was in moonlight. Perhaps if we kept on walking along the embankment, the years would actually roll back in time.

When we got to the edge of the bank, we turned around and walked back until we reached the entrance to the embankment, and then we made another round trip. The whole time, we held each other’s hand tightly. We hardly spoke a word; we just kept walking back and forth along the embankment.

“Shall we go home?” I said, when we came back to the entrance for the umpteenth time. Kojima was silent for a moment until he suddenly let go of my hand.

“I guess so,” he replied quietly.

We descended from the embankment side by side. It was close to midnight. The moon had climbed high in the sky.

“I thought we might just keep walking until dawn,” Kojima murmured. He didn’t turn toward me when he spoke; he seemed to be whispering these words to the sky.

“I know what you mean,” I replied. Kojima stared at me now.

We held each other’s gaze for a long moment. Then, without a word, we crossed the street. Kojima hailed a taxi as it sped toward us, and put me inside.

“If I see you home, I’ll just get more ideas in my head,” Kojima said, smiling.

“All right then,” I said, at the same time that the taxi driver slammed the automatic door closed and then sped off.

I turned and watched Kojima’s figure retreat from the rear window. It got smaller and smaller, and then disappeared.

Maybe it wouldn’t be such a bad thing to get ideas in your head, I muttered softly to myself in the backseat of the taxi. But I was well aware of what would be likely to go wrong in the aftermath. Maybe Sensei was by himself at Satoru’s place. Perhaps he was eating salted yakitori. Or else he was cozied up with Ms. Ishino, at the odenya or somewhere.

Everything felt so far away. Sensei, Kojima, the moon—they were all so distant from me. I stared out the window, watching the streetscape as it rushed by. The taxi hurtled through the nighttime city. Sensei, I forced out a cry. My voice was immediately drowned out by the sound of the car’s engine. I could see many cherry trees in bloom as we sped through the streets. The trees, some young and some many years old, were heavy with blossoms in the night air. Sensei, I called out again, but of course no one could hear me. The taxi carried me along, speeding through the city night.

Lucky Chance

TWO DAYS AFTER the cherry blossom party, I saw Sensei at Satoru’s place, but I was just paying my bill when he walked in, so all we said was hello and then parted.

The week after the next, our paths crossed at the tobacco shop in front of the station, but this time Sensei seemed to be in a hurry. All we did was nod at each other and then we parted.

And then it was May. The trees along the streets and the copse next to where I lived grew flush with fresh green leaves. There were days when it seemed hot even in short sleeves, and then there were chilly days that made me long to huddle under the kotatsu. I visited Satoru’s place several times, and I kept assuming I’d run into Sensei, but I never saw him there.

Sometimes from across the counter, Satoru would ask something like “Tsukiko, do you miss having your dates with Sensei?”

And I would reply, “We never had any dates.”

“Is that so?” Satoru would sniff.

I could do without his sniffing. I picked at my flying fish sashimi indifferently. Satoru watched with a critical eye as I decimated it. Too bad for the flying fish. But it wasn’t my fault. Satoru shouldn’t have been the one to go sniffing, “Is that so?”

I continued mistreating the fish. Satoru went back to his cutting board to prepare another customer’s order. The flying fish’s head shone on the plate. Its wide-open eyes were limpid. With renewed determination, I seized a piece of the fish with my chopsticks and dunked it in gingered soy sauce. The firm flesh had a slightly peculiar flavor. I sipped from my glass of cold saké and looked around the bar. Today’s menu was written in chalk on the blackboard. Minced bonito. Flying fish. New potatoes. Broad beans. Boiled pork. If Sensei were here, he would definitely order the bonito and the broad beans first.

“Speaking of Sensei, the last time I saw him here he was with a beautiful lady,” the fat guy in the seat next to me said to Satoru. Satoru barely looked up from his chopping block and, without replying to the guy, he shouted to the interior of the bar, “Bring me one of the blue platters!” A young man appeared from where the back sink was.

“Hey,” the fat guy said.

“He’s the newbie,” Satoru said by way of introduction.

The young man bowed his head and said, “Nice to meet you.”

“He looks a bit like you, boss,” the guy said.

Satoru nodded. “He’s my nephew,” he said, and the young man bowed his head once again.

Satoru heaped sashimi onto the platter that the young man had brought from the back. The fat guy stared for a moment at the retreating figure of Satoru’s nephew, but soon turned his full attention to his bar snacks.

Shortly after the fat guy left, the other patrons settled up too and the bar was suddenly empty. I could hear the sound of the young man running water in the back. Satoru took a small container from the refrigerator and placed what was inside on two small plates. He set one of the plates in front of me.

“My wife made this recipe, if you care to try it,” Satoru said, scooping up some of the other plateful of “his wife’s recipe” with his fingers and tossing it in his mouth. The “recipe” was konnyaku, which had been stewed with a stronger flavor than the way Satoru made it. This konnyaku was piquant with red pepper.

It’s good, I said to Satoru, who gave me a serious look and nodded, then scooped up another mouthful. Satoru flipped on the radio that he kept atop a shelf. The baseball game was over and the news was about to start. Advertisements blared one after another for cars and department stores and instant rice with green tea.

“So has Sensei been in here much lately?” I asked Satoru, trying to be as lackadaisical as I could.

“Well, you know,” Satoru nodded vaguely.

“That guy who was in here before, he said Sensei’d been here with a beautiful lady.” This time I was going for the pleasant, bantering gossip of a regular customer. I’m not actually sure how successful I was, though.

“Um, let’s see, I don’t really remember,” Satoru replied, keeping his head down.

Hmm, I murmured. Hmm, I see.

Both Satoru and I fell silent. On the radio, a reporter was expounding on a theory about a random serial killing spree in another prefecture.

“What kind of person…?” Satoru said.

“What is the world coming to?” I answered.

Satoru listened carefully to the rest of the report and then said, “People have been wondering the same thing for over a thousand years.”

Laughter from the young man in the back rang out softly. We could hear him chuckling for a moment but we couldn’t tell if he was laughing at what Satoru had said or at something completely unrelated. Could I please have my bill, I said, and Satoru tallied it up in pencil on a piece of paper. Satoru thanked me as I parted the curtain and headed outside, where the nighttime breeze braced against my cheeks. I shivered as I flung the door closed behind me. The wind carried a dampness that smelled like rain. A drop fell on my head. I quickened my pace and headed home.

IT RAINED FOR the next several days. The color of the young leaves on the trees suddenly intensified—when I looked out the window, everything was green. There was a cluster of still-young zelkova trees growing in front of my apartment. Their green leaves shone glossy and lustrous, battered by the rain. I got a phone call from Takashi Kojima on Tuesday.

“Do you want to go to the movies?” Kojima asked.

Sure, I replied, and I heard him sigh on the other end of the line.

“What’s the matter?”

“I’m just nervous. I feel like I’m back in school,” Kojima said. “The first time I asked a girl on a date, well, I actually wrote out something like a flow chart of how the conversation might go.”

Did you make a flow chart today? I asked.

Kojima answered, “Oh, no,” in a serious tone. “But I will admit that I thought about it.”

We made plans to meet on Sunday in Yurakucho. Kojima seemed like a classic type. After the movie, we could get something to eat, he had said. By which he undoubtedly meant a fancy Western-style restaurant in Ginza. One of those great places that have been there forever and serve things like tongue stew or cream croquettes.

I thought I might get my hair cut before seeing Kojima, so I went out on Saturday afternoon. Perhaps because of the rain, there weren’t as many people out as usual. I walked through the shopping district, twirling my umbrella. How many years had it been that I’d lived in this neighborhood? After I left home, I lived in another part of the city but, like a salmon that returns to the stream of its birth, at some point I ended up back here, in the neighborhood where I grew up.

“Tsukiko.” I turned around when I heard my name and saw Sensei standing there. He had on black rain boots and was wearing a raincoat with the belt fastened neatly.

“It’s been a long time,” he said.

Yes, I replied. It’s been a long time.

“You left early, that time at the cherry blossom party.”

Yes, I said once more. But I came back again, I added in a quiet voice.

“After the party, I took Ms. Ishino to Satoru’s bar.”

He seemed not to have heard me say that I had come back again. Oh? You took her there? Isn’t that nice, I replied dispiritedly. Why was it that when I talked to Sensei I suddenly felt depressed and indignant and strangely sentimental? And I had never been one to wear my emotions on my sleeve.

“Ms. Ishino is quite a genial person, you know. Even Satoru warmed right up to her.”

Well, that’s Satoru’s job, to be nice to the customers, isn’t it? But I swallowed my words. Wouldn’t this seem to suggest that I was, in fact, feeling jealous toward Ms. Ishino? But that was not the case. I’d be damned if it was.

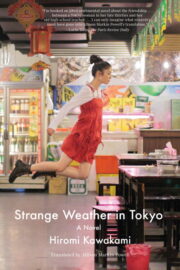

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.