“I’ve never understood…,” Sensei murmured, gazing up at the seagulls in the sky. “It seems that, even now, I still dwell on my wife.”

The words “even now” reached me between the seagulls’ cries. Even now. Even now. Did you bring me all the way to this desolate island just to tell me that? I screamed in my head. But, of course, I didn’t say this either. I stared at Sensei. He wore a soft smile. What the hell was he smiling so blithely about?

“I’m going back to the guesthouse,” I said finally, turning my back on Sensei.

Tsukiko, I thought I heard him call out after me, but I might have been imagining it. I followed along the path from the cemetery to the marsh at a trot, passing through the hamlet and down the hill. I kept turning around but Sensei wasn’t following me. I thought I heard his voice call out my name again.

Sensei, I called back. The seagulls wouldn’t shut up. I waited a moment, but I didn’t hear Sensei’s voice again. Apparently, he wasn’t coming after me. Was he sitting alone in the cemetery, praying? Feelingly? About his wife that he still dwells on? His dead wife?

Old bastard, I said to myself, and then I repeated it out loud. “Old bastard!” The old bastard must be taking a brisk walk around the island. I should just forget about him and go soak in the little outdoor hot spring at the guesthouse. Since I’m here on this island anyway. I’m going to enjoy myself on this trip whether Sensei is with me or not. I’ve managed on my own until now anyhow. I drink by myself, I get drunk by myself, and I have a good time by myself, don’t I?

I made my way down the hill with determination. The setting sun was still hovering over the water, about to disappear. The loud pattering of my sandals annoyed me. The seagulls’ cries that filled the entire island were relentless. The new dress I had worn especially for this trip was uncomfortable around my waist. The too-big sandals had made my insteps hurt. The road and the beach without a soul to be seen were lonesome. And Sensei—damn him for not coming after me—had pissed me off.

This was just what my life was like, after all. Here I was, trudging alone on an unfamiliar road, on some unfamiliar island, separated from Sensei—whom I thought I knew but didn’t know at all. There was no reason not to start drinking. I had heard that the island’s specialties were octopus, abalone, and giant prawns. I was going to eat a shitload of abalone. Sensei had invited me, so it ought to be his treat. And tomorrow when I’m so hungover I can’t walk, he can carry me on his back. I would totally forget about whatever notions I had momentarily entertained regarding what it might be like to spend time with Sensei.

The lights under the guesthouse’s eaves were illuminated. Two large seagulls were perched on the roof. Hunched and still, they looked like guardian deities on the edge of the roof tiles. It was now completely dark and, without my noticing it, the seagulls’ cries had ceased. As I rattled open the front door of the guesthouse, I called out, I’m back. I heard a cheerful voice from inside say, Welcome back! The aroma of freshly cooked rice wafted toward me. Looking out from inside, it was pitch-black.

Sensei, it’s dark, I murmured. Sensei, come back, it’s already dark. I don’t care if you’re still dwelling on your wife or whatever, just hurry back and let’s have a drink together. My earlier anger was now completely forgotten. We don’t have to be teatime companions, we can just be drinking buddies. I’d like nothing more than that. Hurry back now, I murmured over and over, out toward the dark night. I thought I saw Sensei’s silhouette in the dimness on the hill outside the guesthouse. But there wasn’t a silhouette at all, not even a shadow to be seen, only darkness. Sensei, hurry back, I would go on murmuring forever.

The Island, Part 2

“LOOK, TSUKIKO, THE octopus is floating to the top,” Sensei pointed out, and I nodded.

It was sort of like an octopus version of shabu-shabu. Thin, almost-transparent slices of octopus were submerged in a gently boiling pot of water, and then immediately plucked out with chopsticks when they rose to the surface. Dipped in ponzu sauce, the sweetness of the octopus melted in your mouth with the ponzu’s citrus aroma, creating a flavor that was quite sublime.

“See how the octopus’s translucent flesh turns white when you put it in hot water,” Sensei chatted exactly the same way as if he and I were sitting and drinking at Satoru’s place.

“It’s white, yes.” I, on the other hand, was decidedly unsettled. I had no idea whether I ought to smile or be quiet, or how I should behave at all.

“But, just before, there’s a moment when it appears ever so slightly pink, don’t you see?”

“Yes,” I replied quietly. Sensei looked at me with a bemused expression and then helped himself to three slices of octopus at once from the pot.

“You’re awfully acquiescent tonight, Tsukiko.”

Sensei had finally come down the hill after a really long time. The seagulls’ cries had fallen completely silent and the darkness had grown thick and dense. A really long time, I thought, but then again it may not have been more than five minutes. I had stood and waited for him at the guesthouse’s front door. He had returned, his footsteps light and not the least bit uncertain in the dark. When I called out to him, “Sensei,” he replied, “Ah, Tsukiko, I’m back.” As we headed into the guesthouse together, I said, “Welcome back.”

“Such splendid abalone!” Sensei exclaimed as he lowered the flame under the pot of octopus shabu-shabu. Four abalone shells were lined up on a medium-sized plate, each shell filled with abalone cut into sashimi.

“Have your fill, Tsukiko.”

Adding a little wasabi, Sensei dunked a piece of abalone in soy sauce. He chewed it slowly. When he was chewing, his mouth was that of an old man. I chewed my abalone. I hoped that my mouth was still that of a young woman, but if not, I was resigned to that too. I felt very strongly about it at that moment.

Octopus shabu-shabu. Abalone. Mirugai. Kochi fish. Boiled shako. Fried giant prawns. They were served one after another. By now, the pace of Sensei’s chopsticks began to slow. He barely tipped his saké, taking small sips. I inhaled the rapid-fire offerings, drinking cup after cup without saying much of anything.

“Are you enjoying the food, Tsukiko?” Sensei asked, as if he were indulging a grandchild with a voracious appetite.

“It’s delicious,” I replied brusquely, then I repeated myself, this time with a bit more enthusiasm.

By the time they brought out the cooked and pickled vegetables, both Sensei and I had eaten our fill. We decided not to have any rice, just some miso soup. The two of us finished our saké leisurely as we sipped the soup, rich with fish stock.

“Well, is it about time to go?” Sensei stood up, holding his room key. I followed him to stand, but apparently the saké had had more of an effect than I realized and my feet were unsteady. I stumbled as I took a step, falling forward onto my hands on the tatami.

“Oh, dear,” Sensei said, looking down at me.

“Stop with your ‘Oh, dear’ and give me a hand!” I sort of shouted, and Sensei laughed.

“There, now you sound like Tsukiko!” he said, holding out a hand. I took it and climbed the steps. We stopped outside Sensei’s room, which was halfway down the corridor. Sensei put his key in the lock. It made a clicking sound. I stood there, swaying in the hall, as I watched Sensei’s back.

“You know, Tsukiko, the hot spring at this guesthouse is supposed to be quite good,” Sensei turned around to say.

All right, I replied vacantly, still swaying.

“Once you’ve gathered yourself, go take a bath.”

All right.

“It will sober you up a bit.”

All right.

“Once you’ve taken the waters, if the night is still long, come to my room.”

This time, instead of replying All right again, my eyes widened. What? What do you mean by that?

“I don’t mean anything by that,” Sensei answered, disappearing behind the door.

The door closed before me and I was left standing in the corridor, now only slightly swaying. In my saké-addled mind, I ruminated on what Sensei had said. Come to my room. He had definitely said those words. But, if I went to his room, what exactly would happen? Surely we wouldn’t just be playing cards. Maybe we’d keep drinking. Then again, it was Sensei—he might suddenly suggest, “Let’s write some poetry,” or something like that.

“Now, Tsukiko, don’t get your hopes up,” I muttered, heading for my own room. I unlocked the door and flipped on the light switch, and there in the middle of the room, my single bedding had been laid out. My luggage had been moved in front of the alcove.

As I changed into a yukata and got ready for the bath, I repeated over and over, “Don’t get your hopes up, don’t get your hopes up.”

THE HOT SPRING made my skin soft. I washed my hair, immersing myself in the bath over and over, and by the time I had painstakingly blown my hair dry in the changing room, to my surprise, more than an hour had passed.

I went back to my room and opened the window, letting the night air rush in. The crashing of the waves sounded much louder now. I leaned against the window sash for a while.

Since when had Sensei and I become close like this? At first, Sensei had been a distant stranger. An old, unfamiliar man who in the faraway beyond had been a high school teacher of mine. Even once we began chatting now and then, I still barely ever looked at his face. He was just an abstract presence, quietly drinking his saké in the seat next to mine at the counter.

It was only his voice that I remembered from the beginning. He had a resonant voice with a somewhat high timbre, but it was rich with overtones. A voice that emanated from the boundless presence by my side at the counter.

At some point, sitting beside Sensei, I began to notice the heat that radiated from his body. Through his starched shirt, there came a sense of Sensei. A feeling of nostalgia. This sense of Sensei retained the shape of him. It was dignified, yet tender, like Sensei. Even now, I could never quite get a hold on this sense—I would try to capture it, but the sense escaped me. Just when I thought it was gone, though, it would cozy back up to me.

I wondered, for instance, if Sensei and I were to be together, whether that sense would temper into solidity. But then again, wasn’t a sensation just that kind of indistinct notion that slips away, no matter how you try to contain it?

A large moth flew into my room, attracted by the light. It flitted about, scattering the scales from its wings. I pulled the cord on the lamp, and the bright white light of the bulb softened to an orange glow. The moth idly fluttered about before finally drifting back outside.

I waited a moment, but the moth did not return.

I closed the window, retied the obi on my yukata, applied a little lipstick, and grabbed a handkerchief. I went out into the corridor, trying not to make a sound as I locked the door. Several small moths had gathered around the light in the hallway. Before knocking on Sensei’s door, I took a deep breath. I pressed my lips together lightly, smoothed my hair with the palm of my hand, and then took another deep breath.

“Sensei,” I called out, and from within I heard the reply, “It’s open.” I carefully turned the doorknob.

Sensei was resting his elbows on the low table. He was drinking a beer, his back to the bedding that had been moved off to the side.

“Is there no saké?” I asked.

“No, there’s some in the refrigerator, but I’ve had enough already,” he said as he tilted a five-hundred-milliliter bottle of beer. The foam rose cleanly in his glass. I took a glass that was upside down on a tray on top of the refrigerator.

Please, I said, holding it out in front of Sensei. He smiled and poured the same clean head of beer for me.

There were a few triangular pieces of cheese wrapped in silver foil on the table.

“Did you bring those with you, Sensei?” I asked, and he nodded.

“You came prepared.”

“I thought of it just as I was leaving and threw them in my briefcase.”

The night was tranquil. The sound of the waves could be heard through the window. Sensei opened a second bottle of beer. The popping sound of the bottle opener echoed throughout the room.

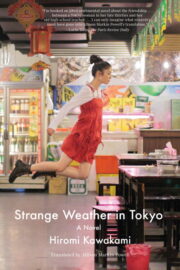

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.