By the time we finished the second bottle, both of us had fallen silent. Every so often the sound of the waves grew louder.

“It’s so quiet,” I said, and Sensei nodded.

A little while later, Sensei said, “It’s very quiet,” and this time I nodded.

The silver foil wrappers from the cheese had been peeled off and lay curled up on the table. I gathered the foil into a ball. I suddenly remembered how, when I was little, I had collected the silver foil from chocolate fingers and had fashioned a rather large ball out of them. I would carefully unfold each piece, flattening them out as best I could. Occasionally, I came across a gold wrapper, and I would set these aside. I had a vague memory of saving these in the bottom drawer of my desk, with the idea to use them as a Christmas tree topper. But then, when Christmas came round, I seem to recall that the gold paper had gotten buried under my notebooks and my modeling clay set, and had been crushed and wrinkled.

“It’s so quiet.” Who knows how many times we’d said it, but this time Sensei and I had both said it at the same time. Sensei adjusted his seat on the cushion. I did the same. I sat across from Sensei, playing with the silver foil ball in my hands.

Sensei opened his mouth as if to say, “Oh,” but no sound came out. His open mouth showed signs of his age. Much more so than earlier, when he had been chewing the abalone. Softly, I averted my gaze. Sensei did the same.

The sound of the waves was constant.

“Perhaps it’s time to go to sleep,” Sensei said quietly.

“Yes,” I replied. What else was there to say? I stood up and closed the door behind me, and I walked back to my room. There were now even more moths clustered around the light in the hallway.

I AWOKE WITH a start in the middle of the night.

My head hurt a little. There was no sign of anyone else in my room. I tried to revive that indefinite sense of Sensei without much success.

Once I wake up I never get back to sleep. The ticking of my watch by the pillow rang in my ears. Just when I thought it was so close, it would recede. But the watch was always in the same place. How strange.

For a while I just lay still. Then I began to stroke my own breast under my yukata. It was neither soft nor hard. I let my hand slip down to caress my belly. My belly felt very smooth. And further on down. My palm brushed against something warm. Despite my idle touch, though, it wasn’t the least bit pleasurable. Then I thought about whether I had any hope or expectation about being touched by Sensei, and whether that would be pleasurable, but that seemed futile as well.

I must have lain there for about thirty minutes. I thought I might fall back asleep, just listening to the sound of the waves, but instead I was wide-awake. I wondered what the chances were that Sensei too was lying there, awake in the dark.

Once the thought occurred to me, the idea steadily expanded in my mind. Soon enough, I became convinced that Sensei was calling me from the other room. If not kept in check, nighttime thoughts are prone to amplification. I couldn’t lie still any longer. Without turning on the light, I opened the door to my room very quietly. I went to the bathroom at the end of the corridor and used the toilet. I thought that if my bladder could relax, perhaps my exaggerated mood might deflate as well. But my mind still wasn’t the least bit eased.

I returned to my room and applied a bit of lipstick, then I tiptoed over to Sensei’s room. I put my ear to the door, trying to listen inside. Just like a thief. Rather than the sound of him breathing, I could hear some other kind of sound. I stood there for a moment, listening carefully, and now and then the sound grew louder. Sensei, I whispered. Sensei, what’s the matter? Are you all right? Is there something wrong? Should I come in?

SUDDENLY THE DOOR opened. I shut my eyes against the flood of light from within the room.

“Tsukiko, don’t just stand there, come inside!” Sensei beckoned to me. Once I had opened my eyes, they adjusted to the light immediately. It appeared that Sensei had been doing some kind of writing. Papers were strewn about the table.

What are you writing? I asked, and Sensei picked up a sheet of paper from the table to show me.

OCTOPUS FLESH, FAINTLY RED was written on the page. I gazed at it for a good long while, and then Sensei said, “I can’t seem to come up with the final syllables.”

He mused, “What might come after ‘faintly red’?”

I flopped down to sit on a cushion. While I had been agonizing over my feelings for Sensei, he had been agonizing over the puzzle of the octopus.

“Sensei,” I said in a low voice. Sensei raised his head absently. On one of the sheets strewn on top of the table, there was a lame attempt at a drawing of an octopus. The octopus had a dotted hachimaki tied around its head.

“What is it, Tsukiko?”

“Sensei, that…”

“Yes?”

“Sensei, this…”

“Yes?”

“Sensei.”

“Whatever’s the matter, Tsukiko?”

“How about ‘the roaring sea’?”

I could not seem to bring myself to the heart of the matter. I wasn’t even sure if there was such a thing as “the heart of the matter” between Sensei and me.

“Oh, you mean, ‘Octopus flesh, faintly red, the roaring sea’?”

Sensei paid no attention to my desperate state at all, or else he pretended not to notice, as he wrote the verse on the page. Octopus flesh, faintly red, the roaring sea, he recited as he wrote.

“That’s quite good. Tsukiko, you have a fine aesthetic.”

I murmured a vague reply. Furtively, so that Sensei wouldn’t see, I brought a piece of scrap paper to my lips and wiped away the lipstick. Sensei muttered to himself as he fine-tuned the haiku.

“Tsukiko, what do you think of ‘The roaring sea, octopus flesh, faintly red’?”

There was nothing to think about it. I parted my now colorless lips to murmur another vague response. Having transferred the poem to the page with obvious delight, Sensei now shook his head, somewhat skeptically.

“It’s Basho,” Sensei said. I didn’t have it in me to reply, all I could do was simply nod my head. Basho’s poem is “The darkening sea, a wild duck calls, faintly white.” As he continued writing, Sensei began to lecture. Here, now, in the middle of the night.

You could say that the haiku we have written together is based on Basho’s haiku. It has an interesting broken meter. “The darkening sea, faintly white, a wild duck calls” doesn’t work, because this way “faintly white” carries over to both the sea and the duck’s call. When it comes at the end, it brings the whole haiku to life. Do you understand? See? Tsukiko, go ahead, write another poem.

So, with no choice, I found myself sitting there with Sensei, writing poetry. How did this come about? It was already past two o’clock in the morning. What was the state of affairs that had me counting out syllables on my fingertips and scribbling out mediocre poetry like “Moths at evening, in loneliness, circle the lantern.”

Furious, I wrote out verses. Despite the fact that I had never in my life written haiku or the like, I churned out poems, dozens of them. At last, exhausted, I laid my head down on Sensei’s futon and sprawled out on the tatami. My eyelids closed, and I was powerless to open them. I was barely conscious of my body being dragged (it must have been Sensei doing the dragging) to lie in the middle of the futon, but when I awoke, I could still hear the sound of the waves, and light shone through the opening in the curtains.

Feeling a bit cramped in, I glanced around and found Sensei sleeping beside me. I had been sleeping against his arm as a pillow. I let out a little cry and sat up. Then, without thinking, I fled back to my room. I dove under the covers of my own futon, then quickly leapt back out, paced circles around the room—opening the curtains, closing the curtains—before diving back under the covers and pulling the quilt up over my head. Then, leaping from the futon once again and with my mind totally blank, I returned to Sensei’s room. Sensei was waiting for me there, eyes wide open but still in bed in the dimly lit room with the curtains drawn.

“Tsukiko, there you are,” Sensei said softly as he moved to the edge of the futon.

Yes, I said quietly, diving under the covers. The sense of Sensei washed over me. Sensei, I said, burying my face in his chest. Sensei kissed my hair again and again. He touched my breasts over my yukata, and then not over my yukata.

“Such lovely breasts,” Sensei said. His tone was the same as when he had been explaining Basho’s poetry. I chuckled, and so did Sensei.

“Such lovely breasts. Such a lovely girl you are, Tsukiko,” Sensei said as he caressed my face. He caressed my face, over and over. His caresses made me sleepy. I’m going to fall asleep, Sensei, I said, and he replied, Then go to sleep.

I don’t want to sleep, I murmured, but I couldn’t keep my eyes open any longer. It was as if his palms had some kind of hypnotic effect. I don’t want to sleep. I want to stay here in your arms, I tried to say, but I couldn’t get the words out. I don’t want to… don’t want to… don’t want… to…, at last my utterances broke apart. At some point, Sensei’s hand stopping moving as well. I could hear his light sleeping breath. Sensei, I said, summoning the last of my strength.

Tsukiko, Sensei seemed to rouse himself in reply.

As I drifted off to sleep, I could faintly hear the seagulls’ cries above the sea. Sensei, don’t go to sleep, I tried to say, but I couldn’t. I was being pulled down into a deep sleep, there within Sensei’s arms. I gave in to it. I let myself be dragged down into my own slumber, far removed from Sensei’s slumber. The seagulls called out their cries in the morning light.

The Tidal Flat—Dream

I THOUGHT I heard a rustling murmur. It was the camphor tree outside the window. Come here, it sounded like, or Who are you? I stuck my head out the open window to look and see. A number of small birds were flitting about among the branches of the camphor tree. They were fast, and I couldn’t catch sight of them. I only knew they were there because the leaves moved around them as they fluttered about.

In the cherry trees in Sensei’s garden, I’d seen birds before, come to think of it. It was nighttime. The birds would flap their wings a few times and then settle down. These little birds in the camphor tree, they weren’t settling down at all. They just kept fluttering about. And the camphor tree kept murmuring, Come here.

I hadn’t seen Sensei for some time now. Even when I went to Satoru’s place, I still did not come across him sitting there at the counter.

As I listened to the murmur of the branches of the camphor tree, Come here, I decided to go back to Satoru’s that night. Broad beans were now out of season, but surely the first edamame would have arrived. The little birds continued their flitting about, rustling the greenery.

“HIYA-YAKKO,” I ORDERED chilled tofu from my seat at the end of the counter. Sensei wasn’t here. He wasn’t seated on the tatami or at one of the tables either.

Even after I drank down my beer and switched to saké, Sensei still did not appear. The thought of going to his house occurred to me, but that would be presumptuous. While I sat there, distractedly in my cups, I started to grow tired.

I went into the bathroom, and while I sat there, I looked out the small window. As I did my business, I mused that there must be a poem about how depressing it is to look out the window in a toilet and see blue sky. I would say that a window in a toilet would definitely make you depressed.

Maybe I should go to Sensei’s house after all, I was thinking to myself as I came out of the bathroom, and there was Sensei, sitting up straight as usual in the seat two over from mine.

“Here you are, hiya-yakko,” Satoru said as Sensei took the bowl he passed over the counter. Sensei carefully doused it with soy sauce. Gently, he picked some of the tofu with his chopsticks and brought it to his lips.

“It’s tasty,” Sensei said straightaway, facing me. Without any greeting or introduction, he spoke as if continuing a conversation we had been having all along.

“I ate some earlier myself,” I said, and Sensei nodded lightly.

“Tofu is quite special.”

“Yes.”

“It’s good warm. It’s good chilled. It’s good boiled. It’s good fried. It’s versatile,” Sensei said readily, taking a sip from the small saké cup.

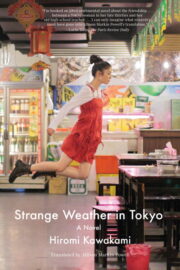

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.