he said.

“So you are! Very smart ones too!” she replied admiringly.

“If I was at home,” said Master Rayne, with a darkling glance at his parent, “I wouldn’t have to wear them.”

“Now, Edmund—!”

“But I expect you are enjoying your visit to London, are you not?” asked Phoebe, diplomatically changing the subject.

“Indeed he is!” said Ianthe. “Only fancy! his grandpapa promises to take him riding in the Park one morning, doesn’t he, my love?”

“If I’m good,” said Edmund, with unmistakable pessimism. “But I won’t have my tooth pulled out again!”

Ianthe sighed. “Edmund, you know Mama said you should not go to Mr. Tilton this time!”

“You said I shouldn’t go when we came to London afore,” he reminded her inexorably. “But Uncle Vester said I should. And I did. I do not like to have my tooth pulled out, even if I am let keep it in a little box, and people do not throw it away,” said Edmund bitterly.

“No one does,” intervened Phoebe. “I expect, however, that you were very brave.”

“Yes,” acknowledged Edmund. “Acos Uncle Vester said he would make me sorry if I wasn’t, and I don’t like Uncle Vester’s way of making people sorry. It hurts!”

“You see!” said Ianthe in a low voice, and with a speaking look at Phoebe.

“Keighley said I was brave when I fell off my pony,” disclosed Edmund. “Not one squeak out o’ me! Full o’ proper spunk I was!”

“Edmund!” exclaimed Ianthe angrily. “If I have told you once I won’t have you repeating the vulgar things Keighley says to you I have told you a hundred times! Beg Miss Marlow’s pardon this instant! I don’t know what she must think of you!”

“Oh, no, pray do not bid him do so!” begged Phoebe, perceiving the mulish set to Master Rayne’s jaw.

“Keighley,” stated Edmund, the light of battle in his eye, “is a prime gun! He is my partickler friend.”

“I don’t wonder at it,” returned Phoebe, before Ianthe could pick up this gage. “I am a little acquainted with him myself, you know, and I am sure he is a splendid person. Did he teach you to ride your pony? I wish you will tell me about your pony!”

Nothing loth, Edmund embarked on a catalogue of this animal’s points. By the time Lord Elvaston’s house in Albemarle Street was reached an excellent understanding flourished between him and Miss Marlow, and it was with considerable reluctance that he parted from her. But his mother had had enough of his company, and she sent him away to the nursery, explaining to Phoebe that if she allowed him to remain with her once he would expect to do so always, which would vex Lady Elvaston. “Mama doesn’t like him to play in the drawing-room, except for half an hour before he is put to bed.”

“I thought you said that she doted on him!” said Phoebe, forgetting to check her unruly tongue.

“Oh, yes! Only she thinks that it isn’t good for him to be put forward too much!” said Ianthe, with commendable aplomb. “Now I am going to take you upstairs to my bedchamber, so that you may put off your hat and pelisse, for I don’t mean to let you run away in a hurry, I can tell you!”

It was indeed several hours later when the carriage was sent for to convey Phoebe to Green Street; and she was by that time pretty fully informed of all the circumstances of Ianthe’s marriage, widowhood, and proposed remarriage. Before they had risen from the table upon which a light nuncheon had been spread she knew that Sylvester had never wanted to be saddled with his brother’s child; and she had been regaled with a number of stories illustrative of his harsh treatment of Edmund, and the malice which prompted him to encourage Edmund to defy his mother’s authority. Count Ugolino was scarcely more repulsive than the callous individual depicted by Ianthe. Had he not been attached to his twin-brother? Oh, well, yes, in his cold way, perhaps! But never would dearest Harry’s widow forget his unfeeling conduct when Harry, after days of dreadful suffering, had breathed his last. “Held up in his arms, too! You would have supposed him to be made of marble, my dear Miss Marlow! Not a tear, not a word tome! You may imagine how wholly I was overset, too—almost out of my senses! Indeed, when I saw Sylvester lay my beloved husband down, and heard his voice saying that he was dead—in the most brutal way!—I was cast into such an agony of grief that the doctors were alarmed for my reason. I was in hysterics for three days, but he cared nothing for that, of course. I daresay he never even knew it, for he walked straight out of the room without one look towards me, and I didn’t set eyes on him again for weeks!”

“Some people, I believe,” Phoebe said, rendered acutely uncomfortable by these reminiscences, “cannot bring themselves to permit others to enter into their deepest feelings. It would not be right—excuse me!—to suppose that they have none.”

“Oh, no! But reserve is repugnant to me!” said Ianthe, rather unnecessarily. “Not that I believe Sylvester to have feelings of that nature, for I am sure I never knew anyone with less sensibility. The only person he holds in affection is his mama. I own him to be quite devoted to her—absurdly so, in my opinion!”

“But you are fond of the Duchess, I collect?” Phoebe asked, in the hope of giving Ianthe’s thoughts a happier direction. “She is kind to you?”

“Oh, yes, but even she does not perfectly understand the misery of my situation! And I dare not hope that she will even try to prevail upon Sylvester not to tear my child from my arms, because she quite idolizes him. I pity his wife! She will find herself expected to defer in everything to Mama-Duchess!”

“Well, perhaps he won’t have a wife,” suggested Phoebe soothingly.

“You may depend upon it he will, just to keep poor little Edmund out of the succession. Mama is persuaded that he is hanging out for one, and may throw the handkerchief at any moment.”

“I daresay! It takes two to make a marriage, however!”

“Do you mean he might meet with a refusal?”

“Why not?” said Phoebe.

“Sylvester? With all that he has to offer? Of course he won’t! I wish he might, for it would do him good to be rebuffed. Only ten to one if it did happen he would set to work to make the girl fall in love with him, and then offer for another!”

“I see no reason for anyone to fall in love with him,” declared Phoebe, a spark in her eyes.

“No, nor do I, but you would be astonished if you knew how many girls have positively languished over him!”

“I should!” said Phoebe fervently. “For my part I should suppose them rather to have fallen in love with his rank!”

“Yes, but it isn’t so. He can make girls form a tendre for him even when they have started by not liking him in the least. He knows it, too. He bet Harry once that he would succeed in attaching Miss Wharfe, and he did!”

“Bet—?” gasped Phoebe. “How—how infamous! How could any gentleman do such a thing?”

“Oh, well, you know what they are!” said Ianthe erroneously. “I must own, too, that Miss Wharfe’s coldness was one of the on-dits that year: she was a very handsome girl, and a great heiress as well, so of course she had dozens of suitors. She snubbed them all, so that it got to be a famous jest. They used to call her the Impregnable Citadel. Harry told Sylvester—funning, you know: they were always funning!—that even he would not be able to make a breach in the walls, and Sylvester instantly asked him what odds he was offering against it. I believe they were betting heavily on it in the clubs, as soon as it was seen that Sylvester was laying siege to the Citadel. Men are so odious!”

With this pronouncement Phoebe was in full agreement. She left Albemarle Street, amply provided with food for thought. She was shrewd enough to discount much that had been told her of Sylvester’s treatment of his nephew: Master Rayne did not present to the world the portrait of an ill-used child. On the other hand, his mama had unconsciously painted herself in unflattering colours, and emerged from her various stories as a singularly foolish parent. Probably, Phoebe decided, Sylvester was indifferent to Edmund, but determined, in his proud way, to do his duty by the boy. That word had no very pleasant connotation to one who had had it ceaselessly dinned in her ears by an unloving stepmother, but it did not include injustice. Lady Marlow had always been rigidly just.

It was Ianthe’s last disclosure that gave Phoebe so furiously to think. She found nothing in it to discount, for the suspicion had already crossed her mind that Sylvester’s kindness had been part of a deliberate attempt to make her sorry she had so rudely repulsed him. His manners, too, when he had called in Green Street, even the lurking smile in his eyes when he had looked at her, were calculated to please. Yes, Phoebe admitted, he did know how to fix his interest with unwary females. The question was whether to repulse him, or whether, safe in the knowledge that he was laying a trap for her, to encourage his attentions.

The question remained unanswered until the following day, when she met him again. She was riding with her Ingham cousins in the Park in a sedate party composed of herself, Miss Mary and Miss Amabel, young Mr. Dudley Ingham, and two grooms following at a discreet distance; and she was heartily bored. The Misses Ingham were very plain, and very good, and very dull; and their brother, Lord Ingham’s promising second son, was already bidding fair to become a solid member of some future government; and the hack provided for her use was an animal with no paces and a placid disposition.

Sylvester, himself mounted on a neatish bay, and accompanied by two of his friends, took in the situation in one amused glance, and dealt with it in a way that showed considerable dexterity and an utter want of consideration for Lord Yarrow and Mr. Ashford. Without anyone’s knowing (except himself) how it had come about, the two parties had become one; and while his hapless friends found themselves making polite conversation to the Misses Ingham, Sylvester was riding with Phoebe, a little way behind.

“Oh, my poor Sparrow!” he said, mocking her. “Never have I encountered so heartrending a sight! A job-horse?”

“No,” replied Phoebe. “My cousin Anne’s favourite mount. A very safe, comfortable ride for a lady, Duke.”

“I beg your pardon! I have not seen him show his paces, of course.”

She cast him a glance of lofty scorn. “He has none. He has a very elegant shuffle, being just a trifle tied in below the knee.”

“But such shoulders!”

Gravity deserted her; she burst into laughter, which made Miss Mary Ingham turn her head to look at her in wondering reproof, and said: “Oh, dear, did you ever set eyes on such a flat-sided screw?”

“No—or on a lady with a better seat. The combination is quite shocking! Will you let me mount you while you are in town?”

She was so much astonished she could only stare at him. He smiled, and said: “I keep several horses at Chance for my sister-in-law’s convenience. She was used to ride a great deal. There would be nothing easier than for me to send for a couple to be brought up to London.”

“Ride Lady Henry’s horses?” she exclaimed. “You must be mad! I shouldn’t dream of doing such a thing!”

“They are not her horses. They are mine.”

“You said yourself you kept them for her use: she must consider them as good as her own! Besides, you must know I couldn’t permit you to mount me!”

“I suppose you couldn’t,” he admitted. “I hate to see you so unworthily mounted, though.”

“Thank you—you are very good!” she stammered.

“I am what? Sparrow, I do implore you not to let Lady Ingham teach you to utter civil whiskers! You know I am no such thing, but, on the contrary, the villain whose evil designs drove you from home!” He stopped, as her eyes flew involuntarily to meet his. The look held for no more than an instant, but the expression in her eyes drove the laughter from his own. He waited for a moment, and then asked quietly: “What is it? What did I say to make you look at me like that?”

Scarlet-cheeked, she said: “Nothing! I don’t know how I looked.”

“Very much as I saw you look once at your mother-in-law: stricken!”

She managed to laugh. “How absurd! I am afraid you have too lively an imagination, Duke!”

“Well, I hope I may have,” he returned.

“There can be no doubt. I was—oh, shocked to think that after all that has passed you could suppose me to regard you in the light—in the light of a villain. But you were only funning, of course.”

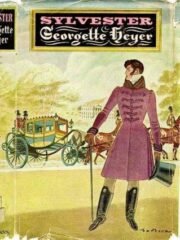

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.