“He won’t care for that now!” she said.

But as Edmund peeped into the coffee-room at that moment, and, upon being applied to by Tom, instantly said that he would not let Phoebe go away, this argument failed. She did suggest to Edmund that his uncle would suffice him, but he vigorously shook his curly head, saying: “No, acos Uncle Sylvester is damned if he will be plagued with me afore breakfast.”

This naive confidence did much to alleviate constraint. Phoebe could not help laughing, and Sylvester, wreaking awful vengeance on his small nephew, lost his stiffness.

But just as Edmund’s squeals and chuckles were at their height the company was startled by a roar of rage and anguish from above-stairs. It seemed to emanate from a soul in torment, making Sylvester jerk up his head, and Edmund stop squirming in his hold.

“What the devil—?” exclaimed Sylvester.

24

“Now what’s amiss?” said Tom, limping to the door. “It sounds as if the Pink of the Ton has found a speck of mud on his coat.”

“Pett! Pett!” bellowed Sir Nugent, descending the stairs. “Pett, where are you? Pett, I say!”

As Tom pulled the door wide Sylvester set Edmund on his feet, demanding: “What in God’s name ails the fellow?”

With a final appeal to Pett as he crossed the hall Sir Nugent appeared in the doorway, nursing in his arms a pair of glossy Hessians, and commanding the occupants of the coffee-room to look—only to look!

“Don’t make that infernal noise!” said Sylvester sharply. “Look at what?”

“That cur, that mongrel!” Sir Nugent shouted. “I’ll hang him! I’ll tear him limb from limb, by God I will!”

“Oh, sir, what is it?” cried Pett, running into the room.

“Look!” roared Sir Nugent, holding out the boots.

They were the Hessians of his own design, but gone were their golden tassels. Pett gave a moan, and fell back with starting eyes; Tom shot one quick look at Edmund, tried to keep his countenance, and, failing, leaned against the door in a fit of unseemly laughter; and Phoebe, after one choking moment, managed to say: “Oh, dear, how very unfortunate! But p-pray don’t be distressed, Sir Nugent! You may have new ones put on, after all!”

“New ones—! Pett! if it was you who left the door open so that that mongrel could get into my room you leave my service today! Now! Now, do you hear me?”

“Never!” cried Pett dramatically. “The chambermaid, sir! the boots! Anyone but me!”

Balked, Sir Nugent rounded on Tom. “By God, I believe it was you! Laugh, will you? You let that cur into my room!”

“No, of course I didn’t,” said Tom. “I’m sure I beg your pardon, but of all the kick-ups only for a pair of boots!”

“Only—!” Sir Nugent took a hasty step towards him, almost purple with rage.

“Draw his cork, Tom, draw his cork!” begged Edmund, his angelic blue eyes blazing with excitement.

“Fotherby, will you control yourself?” Sylvester said angrily.

“Sir, there is no scratch on them! At least we are spared that!” Pett said. “I shall scour Paris day and night, sir. I shall leave no stone unturned. I shall—”

“My own design!” mourned Sir Nugent, unheeding. “Five times did Hoby have them back before I was satisfied!”

“Oh, sir, shall I ever forget?”

“What a couple of Bedlamites!” Sylvester remarked to Phoebe, his eyebrows steeply soaring, his tone one of light contempt.

“Gudgeon,” said Edmund experimentally, one eye on his mentor.

But as Tom was telling Sylvester the tale of Chien’s previous assault on the Hessians this essay passed unheeded. Sir Nugent, becoming momently more like an actor in a Greek tragedy, was lamenting over one boot, while Pett nursed the other, and recalling every circumstance that had led him to design such a triumph of modishness.

Sylvester, losing all patience, exclaimed: “This is ridiculous!”

“Ridicklus!” said Edmund, savouring a new word.

“You can say that?” cried Sir Nugent, stung. “Do you know how many hours I spent deciding between a plain gold band round the tops, or a twisted cord? Do you—”

“I’m not amused by foppery! I shall be—”

“Ridicklus gudgeon!”

“—obliged to you if—What did you say?” Sylvester, arrested by Edmund’s gleeful voice, turned sharply.

The question, most wrathfully uttered, hung on the air. One scared look up into Sylvester’s face and Edmund hung his head. Even Sir Nugent ceased to repine, and waited for the answer. But Edmund prudently refrained from answering. Sylvester, with equal prudence, did not repeat the question, but said sternly: “Don’t let me hear your voice again!” He then turned back to the bereaved dandy, and said: “I shall be obliged to you if you will bring this exhibition to a close, and give me your attention!”

But at this moment the Young Person arrived on the scene, with an urgent summons from Ianthe. Miladi, alarmed by the sounds that had reached her ears, desired her husband to come up to her room immediately.

“I must go to her!” announced Sir Nugent. “She will be in despair when she learns of this outrage! “Nugent,” she said, when I put them on yesterday—the first time! only once worn! “You will set a fashion!” she said. I must go to her at once!”

With that, he laid the boot he was still holding in Pett’s arms, and hurried from the room. Pett, with a deprecating look at Sylvester, said: “Your grace will forgive us. It is a sad loss—a great blow, your grace!”

“Take yourself off!”

“Yes, your grace! At once, your grace!” said Pett, bowing himself out in haste.

“As for you,” said Sylvester, addressing his sinful nephew, “if ever I hear such impertinence from you again it will be very much the worse for you! Now go!”

“I won’t do it again!” said Edmund, in a small, pleading voice.

“I said, Go!”

Scarlet-faced, Edmund fled. This painful interlude afforded Phoebe an opportunity to resume hostilities, and she told Sylvester that his conduct was brutal. “It is extremely improper, moreover, to vent your own ill-temper on the poor child! It would have been enough for you to have given him a quiet reproof. I was never more shocked!”

“When I wish for your advice, Miss Marlow, be sure that I will ask for it,” he replied.

She got up quickly, and walked to the door. “Take care what you are about!” she said warningly, as a parting shot. “I am not one of your unfortunate servants, obliged to submit to your odious arrogance!”

“One moment!” he said.

She looked back, very ready to continue to do battle.

“Since Fotherby appears to be unable to think of anything but his boots, perhaps you, Miss Marlow, will be good enough to inform Lady Ianthe of my arrival,” said Sylvester. “Will you also, if you please, pack Edmund’s clothes? I wish to remove from this place as soon as may be possible.”

This request startled her into exclaiming: “You can’t take him away at this hour! Why, it’s past his bedtime already! It may suit you to travel by night, but it won’t do for Edmund!”

“I have no intention of travelling by night, but only of removing to some other hôtel. We shall leave for Calais in the morning.”

“Then you will remove without me!” said Phoebe. “Have you no thought for anyone’s convenience but your own? What do you imagine must be my feelings—if you can condescend to consider anything so trifling? While I was one of Sir Nugent’s party my lack of baggage passed unheeded, but in yours it will not! And if you think I am going to one of the fashionable hotels in a travel-stained dress, and nothing but a small bandbox for luggage, you are very much mistaken, Duke!”

“Of what conceivable importance are the stares or the curiosity of a parcel of hotel servants?” he asked, raising his brows.

“Oh, how like you!” she cried. “How very like you! To be sure, the mantle of your rank and consequence will be cast over me, won’t it? How delightful it will be to become so elevated as to treat with indifference the opinions of inferior persons!”

“As I am not using my title, and my consequence, as you are pleased to call it, is contained in one portmanteau, you will find my mantle somewhat threadbare!” Sylvester flung at her. “However, set your mind at rest! I shall hire a private parlour for your use, so you will at least not be obliged to endure the stares of your fellow-guests!”

At this point Thomas entered a caveat. “I don’t think you should do that, Salford,” he said. “You’re forgetting that the dibs aren’t in tune!”

A look of vexation came into Sylvester’s face. “Very well! We will put up at some small inn, such as this.”

“The inns are most of ’em as full as they can hold,” Tom warned him. “If we have to drive all over the town, looking for a small inn that has rooms for the four of us, we shall very likely be up till midnight.”

“Do you expect me to remain here?” demanded Sylvester.

“Well, there’s plenty of room.”

“If there is room here there will be—”

“No, there will not be room elsewhere!” interpolated Phoebe. “Sir Nugent is hiring the whole house, having turned out the wretched people who were here before us! And why you should look like that I can’t conceive, when it is just what you did yourself, when you made Mrs. Scaling give up her coffee-room for your private use!”

“And who, pray, were the people I turned out of the Blue Boar?” asked Sylvester.

“Well, it so happened that there weren’t any, but I don’t doubt you would have turned them out!”

“Oh, indeed? Then let me tell you—”

“Listen!” begged Tom. “You can be as insulting to one another as you please all the way to Dover, and I swear I won’t say a word! But for the lord’s sake decide what we are to do first! They’ll be coming to set the covers for dinner soon. I don’t blame you for not wanting to stay here, Salford, but what with pockets to let and young Edmund on our hands, what else can we do? If you don’t choose to let Fotherby stand the nonsense you can arrange with Madame to pay your own shot.”

“Well, I am going to put Edmund to bed!” said Phoebe. “And if you try to drag him away from me, Duke, I shall tell him that you are being cruel to me, which will very likely set him against you. Particularly after your cruelty to him!”

On this threat she departed, leaving Sylvester without a word to say. Tom grinned at him. “Yes, you don’t want Edmund to tell everyone you are a Bad Man. He’s got Fotherby regularly blue-devilled, I can assure you! Come to think of it, he’s already set it about that you grind men’s bones for bread.”

Sylvester’s lips twitched, but he said: “It seems to me that Edmund has been allowed to become abominably out of hand! As for you, Thomas, if I have much more of your damned impudence—”

“That’s better!” said Tom encouragingly. “I thought you were never coming down from your high ropes! I say, Salford—”

He was interrupted by the return of Sir Nugent, who came into the room just then, an expression of settled gloom on his countenance.

“Have you told Ianthe that I am here?” at once demanded Sylvester.

“Good God, no! I wouldn’t tell her for the world!” replied Sir Nugent, shocked. “Particularly now. She is very much distressed. Feels it just as I knew she must. You will have to steal the boy while we are asleep. In the middle of the night, you know.”

“I shall do nothing so improper!”

“Don’t take me up so!” said Sir Nugent fretfully. “No impropriety at all! You are thinking you would be obliged to creep into Miss Marlow’s bedchamber—”

“I am thinking nothing of the sort!” said Sylvester, with considerable asperity.

“There you go again!” complained Sir Nugent. “Dashed well snapping off my nose the instant I open my mouth! No question of creeping into her room: she’ll bring the boy out to you. You’ll have to take her along with you, of course, and I’m not sure that Orde hadn’t better go too, because you never know but what her la’ship might bubble the hoax if he stayed behind. The thing is—”

“You needn’t tell me!—Thomas, either you may stop laughing, or I leave you to rot here!—Understand me, Fotherby! I have no need to steal my ward! Neither you nor Ianthe has the power to prevent my removing him. Well, though I am going to do so I have enough respect for her sensibility as to wish not only to inform her of my intention, but to assure her that every care shall be taken of the boy. Now perhaps you will either conduct me to Ianthe, or go to tell her yourself that I am taking Edmund home tomorrow!”

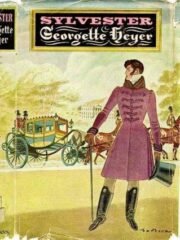

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.