The Duchess’s smile went a little awry. “You haven’t distressed me. It distressed me only to know that Sylvester was still living in some desolate Polar region—but it was only for a moment! I don’t think he is living there any longer.”

“His brother, ma’am?” Phoebe ventured to ask, looking shyly up into her face.

The Duchess nodded. “His twin-brother. They were not alike, but the bond between them was so strong that nothing ever loosened it, not even Harry’s marriage. When Harry died—Sylvester went away. I don’t mean bodily—ah, you understand, don’t you? I might have been sure you would, for I know you to have a very discerning eye. Sylvester has a deep reserve. He will not have his wounds touched, and that wound—” She broke off, and then said, after a little pause: “Well, he kept everyone at a distance for so long that I believe it became, as it were, an engrained habit, and is why he gave you the feeling that he was aloof—which exactly describes him, I must tell you!”

She smiled at Phoebe, and took her hand. “As for his indifferent air, my dear, I know it well—I have been acquainted with it for many years, and not only in Sylvester! It springs, as you so correctly suppose, from pride. That is an inherited vice! All the Raynes have it, and Sylvester to a marked degree. It is inborn, and it wasn’t diminished by his succeeding, when he was much too young, to his father’s dignities. I always did think that the worst thing that could have befallen him, but comforted myself with the thought that Lord William Rayne—he is Sylvester’s uncle, and was guardian to both my sons for the two years that were left of their minority—that William would quickly depress any top-loftiness in Sylvester. But unfortunately William, though the kindest man alive, not only holds himself very much up, but is also convinced that the Head of the House of Rayne is a far more august personage than the Head of the House of Hanover! I have the greatest affection for him, but he is what I expect you would call gothic! He tells me, for instance, that society has become a mingle-mangle, and that too many men of birth nowadays don’t keep a proper distance. He would have given Sylvester a thundering scold for showing incivility to the humblest of his dependants, but I am very sure that he taught him that meticulous politeness was what he owed to his own consequence: noblesse oblige, in fact. So, what with William telling him never to forget how exalted he was, and far too many people looking up to him as their liege-lord, I am afraid Sylvester became imbued with some very improper notions, my dear! And, to be candid with you, I don’t think he will ever lose them. His wife, if he loved her, could do much to improve him, but she won’t alter his whole character.”

“No, of course not, ma’am. I mean—”

“Which, in some ways, is admirable,” continued the Duchess, smiling a little at this embarrassed interjection, but paying no other heed to it. “And the odd thing is that some of his best qualities spring directly from his pride! It would never occur to Sylvester that anyone could dispute his hereditary right of lordship, but I can assure you that it would never occur to him either to neglect the least one of the duties, however irksome, that attach to his position.” She paused, and then said: “The flaw is that his care for his people doesn’t come from his heart. It was bred into him, he accepts it as his inescapable duty, but he hasn’t the love of humanity that inspires philanthropists, you know. Towards all but the very few people he loves I fear he will always be largely indifferent. However, for those few there’s nothing he won’t do, from the high heroical to such tedious things as giving up far too much of his time to the entertainment of an invalid mother!”

Phoebe said, with a glowing look: “He could never think that tedious, I am persuaded, ma’am!”

“Good gracious, of all the boring things to be obliged to do it must surely be the worst! I made up my mind not to permit him to trouble about me, too, but—you may have noticed it!—Sylvester is determined to have his own way, and never more so than when he is convinced he is acting for one’s good.”

“I have frequently thought him—a trifle high-handed, ma’am,” said Phoebe, her eye kindling at certain memories

“Yes, I’m sure you have. Harry used to call him The Dook, mocking his overbearing ways! The worst of it is that it’s so hard to get the better of him! He doesn’t order one to do things: he merely makes it impossible for one to do anything else. Some idiotish doctor once convinced him it would cure me to take the hot bath, and he got me to Bath entirely against my will, and without ever mentioning the name of the horrid place. The shifts he was put to! I forgave him only because he had taken so much trouble over the iniquitous affair! His wife will have much to bear, I daresay, but she will never find him thoughtless where her well-being is concerned.”

Phoebe said, flushing: “Ma’am—you mistake! I—he—”

“Has he put himself beyond forgiveness?” inquired the Duchess quizzically. “He certainly told me he had, but I hoped he was exaggerating.”

“He doesn’t wish to marry me, ma’am. Not in his heart!” Phoebe said. “He only wished to make me sorry I had run away from him, and fall in love with him when it was too late. He couldn’t bear to be beaten, and proposed to me quite against his will—he told me so himself!—and then, I think, he was too proud to draw back.”

“Really, I am quite ashamed of him!” exclaimed the Duchess. “He told me he had made a mull of it, and that, I see, is much less than the truth! I don’t wonder you gave him a set-down, but I am delighted to learn that all his famous address deserted him when he proposed to you! In my experience a man rarely makes graceful speeches when he is very much in earnest, be he never so accomplished a flirt!”

“But he doesn’t want to marry me, ma’am!” averred Phoebe, sniffing into a damp handkerchief. “He told me he did, but when I said I didn’t believe him—he said he saw it was useless to argue with me!”

“Good heavens, what a simpleton!”

“And then I said he was w-worse than Ugolino, and he didn’t s-say anything at all!” disclosed Phoebe tragically.

“That settles it!” the Duchess declared, only the faintest of tremors in her voice. “I wash my hands of such a ninny! After having been given all this encouragement, what does he do but come home in flat despair, saying you won’t listen to him? He even asked me what he should do! I am sure it was for the first time in his life!”

“F-flat despair?” echoed Phoebe, between hope and disbelief. “Oh, no!”

“I assure you! And very disagreeable it made him, too. He brought Mr. Orde up to take tea with me after dinner, and even the tale of Sir Nugent and the button failed to drag more than a faint smile from him!”

“He—he is mortified, perhaps—oh, I know he is! But he doesn’t even like me, ma’am! If you had heard the things he said to me! And then—the very next instant—proposed to me!”

“He is clearly unhinged. I daresay you had no intention of reducing him to this sad state, but I feel you ought, in common charity, to allow him at least to explain himself. Very likely it would settle his mind, and it won’t do for Salford to become addle-brained, you know! Do but consider the consternation of the Family, my dear!”

“Oh, ma’am—!” protested Phoebe, half laughing.

“As for his not liking you,” continued the Duchess, “I don’t know how that may be, but I can’t recall that he ever before described any girl to me as a darling!”

Phoebe stared at her incredulously. She tried to speak, but only succeeded in uttering a choking sound.

“By this time,” said the Duchess, stretching out her hand to the embroidered bell-pull, “he has probably gnawed his nails down to the quick, or murdered poor Mr. Orde. I think you had better see him, my dear, and say something soothing to him!”

Phoebe, tying the strings of her hat in a lamentably lopsided bow, said in great agitation: “Oh, no! Oh, pray—!”

The Duchess smiled at her. “Well, he is waiting in anxiety, my love. If I ring this bell once he will come up in answer to it. If I ring it twice Reeth will come, and Sylvester will know that you would not even speak to him. Which is it to be?”

“Oh!” cried Phoebe, scarlet-cheeked, and quite distracted. “I can’t—but I don’t wish him to—oh, dear, what shall I do?”

“Exactly what you wish to do, my dear—but you must tell him what that is yourself,” said the Duchess, pulling the bell once.

“I don’t know!” said Phoebe, wringing her hands. “I mean, he can’t want to marry me! When he might have Lady Mary Torrington, who is so beautiful, and good, and well-behaved, and—” She stopped in confusion as the door opened.

“Come in, Sylvester!” said the Duchess calmly. “I want you to escort Miss Marlow to her carriage, if you please.”

“With pleasure, Mama,” said Sylvester.

The Duchess held out her hand to Phoebe, and drew her down to have her cheek kissed. “Goodbye, dear child: I hope I shall see you again soon!”

In awful confusion, Phoebe uttered a farewell speech so hopelessly disjointed as to bring a smile of unholy appreciation into the eyes of Sylvester, patiently holding the door.

She ventured to peep at him for one anxious moment, as she went towards him. It was a very fleeting glance, but enough to reassure her on one point: he did not look at all distracted. He was perhaps a little pale, but so far from bearing the appearance of one cast into despair he was looking remarkably cheerful, even confident. Miss Marlow, assimilating this with mixed feelings, walked primly past him, her gaze lowered.

He shut the door, and said with perfect calm: “It was most kind in you to have given my mother the pleasure of making your acquaintance, Miss Marlow.”

“I was very much honoured to receive her invitation, sir,” she replied, with even greater calm.

“Will you do me the honour of granting me the opportunity to speak with you for a few minutes before you go away?”

Her calm instantly deserted her. “No—I mean, I must not stay! Grandmama’s coachman dislikes to be kept waiting for long, you see!”

“I know he does,” he agreed. “So I told Reeth to send the poor fellow home.”

She halted in the middle of the stairway. “Sent him home?” she repeated. “And, pray, who gave you—”

“I was afraid he might take a chill.”

She exclaimed indignantly, “You never so much as thought of such a thing! And you wouldn’t have cared if you had!”

“I haven’t reached that stage yet,” he admitted. “But you must surely own that I am making progress!” He smiled at her. “Oh, no, don’t eat me! I promise you shall be sent back to Green Street in one of my carriages—presently!”

Phoebe, realizing that he was affording her an example of the methods of getting his own way lately described to her by his mother, eyed him with hostility. “So I must remain in your house, I collect, until it shall please your grace to order the carriage to come round?”

“No. If you cannot bring yourself even to speak to me, I will send for it immediately.”

She now perceived that he was not only arrogant but unscrupulous. Wholly devoid of chivalry, too, or he would not have done anything so shabby as to smile at her in just that way. What was more, it was clearly unsafe to be left alone with him: his eyes might smile, but they held besides the smile a very disturbing expression.

“It—it is—I assure you—quite unnecessary, Duke, for you to make me any—any explanation of—of anything!” she said.

“You can’t think how relieved I am to hear you say so!” he replied, guiding her across the hall to where a door stood open, revealing a glimpse of a room lined with bookshelves. “I am not going to attempt anything of that nature, I assure you! I should rather call it disastrous than unnecessary! Will you come into the library?”

“What—what a pleasant room!” she achieved, looking about her.

“Yes, and what a number of books I have, haven’t I?” said Sylvester affably, closing the door. “No, I have not, I believe, read them all!”

“I wasn’t going to say either of those things!” she declared, trying hard not to giggle. “Pray, sir, what is it you wish to say to me?”

“Just my darling!” said Sylvester, taking her into his arms.

It was quite useless to struggle, and probably undignified. Besides, it was a well-known maxim that maniacs must be humoured. So Miss Marlow humoured this dangerous lunatic, putting her arm round his neck, and even going so far as to return his embrace. She then leaned her cheek against his shoulder, and said: “Oh, Sylvester! Oh, Sylvester!” which appeared to give great satisfaction.

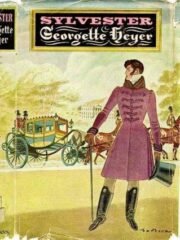

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.