Except for one or two visits to friends living in a different part of the country he had been at home for a year now, enjoying himself very much, and justifying his father’s secret pride in him by taking as much interest in crops as in hounds, and rapidly becoming as popular with the villagers as he was with the neighbouring gentry.

He was a pleasant youth, sturdy rather than tall, with a fresh, open countenance, unaffected manners, and as much of the good sense which characterized his father as was to be expected of a young gentleman of nineteen summers. From the circumstances of his being an only child he had from his earliest youth looked upon Phoebe, just his own age, as a sister; and since she had been, as a child, perfectly ready to engage with him on whatever dangerous pursuit he might suggest to her, besides very rapidly becoming a first-rate horsewoman, and a devil to go, not even his first terms at Rugby had led him to despise her company.

When Phoebe divulged to him her astonishing tidings, he was as incredulous as Susan had been, for, as he pointed out with brotherly candour, she was not at all the sort of girl to achieve a brilliant marriage. She agreed to this, and he added kindly: “I don’t mean to say that I wouldn’t as lief be married to you as to some high flyer, for if I was obliged to marry anyone I think I’d offer for you rather than any other girl I know.”

She thanked him.

“Yes, but I’m not a fashionable duke,” he pointed out. “Besides, I’ve known you all my life. I’m dashed if I understand why this duke should have taken a fancy to you! It isn’t as though you was a beauty, and whenever your mother-in-law is near you behave like a regular pea-goose, so how he could have guessed you ain’t a ninnyhammer I can’t make out!”

“Oh, he didn’t! He wishes to marry me because his mama was a friend of mine.”

“That must be a bag of moonshine!” said Tom scornfully. “As though anyone would offer for a girl for such a reason as that!”

“I think,” said Phoebe, “it is on account of his being a person of great consequence, and wishing to make a suitable alliance, and not caring whether I am pretty, or conversible.”

“He can’t think you suitable!” objected Tom. “He sounds to me a regular knock-in-the-cradle! It may be a fine thing to become a duchess, but I should think you had much better not!”

“No, no, but what am I to do, Tom? For heaven’s sake don’t tell me I have only to decline the Duke’s offer, for you at least know what Mama is like! Even if I had the courage to disobey her only think what misery I should be obliged to endure! And don’t tell me not to regard it, because to be in disgrace for weeks and weeks, as I would be, so sinks my spirits that I can’t even write! I know it’s idiotish of me, but I can’t overcome my dread of being in her black books! I feel as if I were withering!”

He had too often seen her made ill by unkindness to think her words over-fanciful. It was strange that a girl so physically intrepid should have so much sensibility. In his own phrase, he knew her for a right one; but he knew also that in a censorious atmosphere her spirits were swiftly overpowered, none of her struggles to support them alleviating the oppression which transformed her from the neck-or-nothing girl whom no oxer could daunt to the shrinking miss whose demeanour was as meek as her conversation was insipid. He said, rather doubtfully: “You don’t think, if you were to write to him, Lord Marlow would put the Duke off?”

“You know what Papa is!” she said simply. “He will always allow himself to be ruled by Mama, because he can’t bear to be made uncomfortable. Besides, how could I get a letter to him without Mama’s knowing of it?”

He considered for a few moments, frowning. “No. Well—You are quite sure you can’t like the Duke? I mean, I should have supposed anything to be better than to continue living at Austerby. Besides, you said yourself you only once talked to him. You don’t really know anything about him. I daresay he may be rather shy, and that, you know, might easily make him appear stiff.”

“He is not shy and he is not stiff,” stated Phoebe. “His manners are assured; he says everything that is civil because he places himself on so high a form that he would think it unworthy of himself to treat anyone with anything but cool courtesy; and because he knows his consequence to be so great he cares nothing for what anyone may think of him.”

“You did take him in dislike, didn’t you?” said Tom, grinning at her.

“Yes, I did! But even if I had not, how could I accept an offer from him when I made him the villain in my story?”

That made Tom laugh. “Well, you needn’t tell him that, you goose!”

“Tell him! He won’t need telling! I described him exactly!”

“But, Phoebe, you don’t suppose he will read your book, do you?” said Tom.

Phoebe could support with equanimity disparagement of her person, but this slight cast on her first novel made her exclaim indignantly: “Pray, why should he not read it? It is going to be published!”

“Yes, I know, but you can’t suppose that people like Salford will buy it.”

“Then who will?” demanded Phoebe, rather flushed.

“Oh, I don’t know! Girls, I daresay, who like that sort of thing.”

“You liked it well enough!” she reminded him.

“Yes, but that was because it was so odd to think of your having written it,” explained Tom. He saw that she was looking mortified, and added consolingly: “But I’m not bookish, you know, so I daresay it’s very fine, and will sell a great many copies. The thing is that no one will know who wrote it, so there’s no need to tease yourself over that. When does the Duke come to Austerby?”

“Next week. It is given out that he is coming to try the young chestnut. He is going to hunt too, and now Mama is trying to decide whether to dish up all our friends to entertain him at a dinner-party, or to leave it to Papa to invite Sir Gregory Standish and old Mr. Hayle for a game of whist.”

“Lord!” said Tom, in an awed tone.

Phoebe gave a giggle. “That will teach him to come to Austerby in this odious, condescending way!” she observed, with satisfaction. “What is more, Mama does not approve of newfangled fashions, so his grace will find himself sitting down to dinner at six o’clock, which is not at all the style of thing he is accustomed to. And when he comes into the drawing-room after dinner he will discover that Miss Battery has brought Susan and Mary down. And then Mama will call upon me to go to the pianoforte—she has told Sibby already to be sure I know my new piece thoroughly!—and at nine o’clock Firbank will bring in the tea-tray; and at half-past nine she will tell the Duke, in that complacent voice of hers, that we keep early hours in the country; and so he will be left to Papa and piquet, or some such thing. I wish he may be heartily bored!”

“I should think he would be. Perhaps he won’t offer for you after all!” said Tom.

“How can I dare to indulge that hope, when all his reason for visiting us is to do so?” demanded Phoebe, sinking back into gloom. “His mind must be perfectly made up, for he knows already that I am a dead bore! Oh, Tom, I am trying to take it with composure, but the more I think of it the more clearly do I see that I shall be forced into this dreadful marriage, and I feel sick with apprehension already, and there is no one to take my part, no one!”

“Stubble it!” ordered Tom, giving her a shake. “Talking such slum to me! Let me tell you, my girl, that there’s not only me to take your part, but my father and mother as well!”

She squeezed his hand gratefully. “I know you would, Tom, and Mrs. Orde has always been so kind, but—it wouldn’t answer! You know Mama!”

He did, but said, looking pugnacious: “If she tries to bully you into this, and your father don’t prevent her, you needn’t think I shall stand by like a gapeseed! If the worst comes to the worst, Phoebe, you’d best marry me. I daresay we shouldn’t think it so very bad, once we had grown accustomed to it. At all events, I’d rather marry you than leave you in the suds! What the devil are you laughing at?”

“You, of course! Now, Tom, don’t be gooseish! When Mama is so afraid we might fall in love that she has almost forbidden you to come within our gates! She wouldn’t hear of it, or Mr. Orde either, I daresay!”

“I know that. It would have to be a Gretna Green marriage, of course.”

She gave a gasp. “Gretna Green? Of all the hare-brained—No, really, Tom, how can you be so tottyheaded? I may be a hoyden, but I’m not abandoned! Why, I wouldn’t do such a shocking thing even if I were in love with you!”

“Oh, very well!” he said, a trifle sulkily. “I don’t want to do it, and if you prefer to marry Salford there’s no more to be said.”

She rubbed her cheek against his shoulder. “Indeed, I am very much obliged to you!” she said contritely. “Don’t be vexed with me!”

He was secretly so much relieved by her refusal to accept his offer that after telling her severely that it would be well if she learned to reject such offers with more civility he relented, owned that a runaway marriage was not quite the thing, and ended by promising to lend his aid in any scheme she might hit on for her deliverance.

None occurred to her. Lady Marlow took her to Bath to have her hair cut into a smarter crop, and to buy a new dress, in which, presumably, she was to captivate the Duke. But as Lady Marlow considered white, or the palest of blues and pinks, the only colours seemly for a débutante, and nothing showed her to worse advantage, it was hard to perceive how this staggering generosity was to achieve its end.

Two days before the arrival of Lord Marlow and the Duke it began to seem as if one at least of the schemes for his entertainment was to be frustrated. Lord Marlow’s coachman, a weatherwise person, prophesied that snow was on the way; and an item in the Morning Chronicle carried the information that there had been heavy falls already in the north and east. A hope, never very strong, that the Duke would postpone his visit wilted when no message was brought to Austerby from its master, and was speedily followed by something very like panic. If the Duke, who was coming ostensibly to see how he liked the young chestnut’s performance in the hunting-field, was undeterred by the threat of snow he must be determined indeed to prosecute his suit; and if there were no hunting to remove him during the hours of daylight from the house he would have plenty of opportunity to do it. Try as she would Phoebe could not persuade herself that the weather, which had been growing steadily colder, showed any sign of improvement; and when the Squire cancelled the first meeting of the week, and followed that up by going away to Bristol, where some business had been for some time awaiting his attention, it was easy to see that he, the best weather-prophet in the district, had no expectation of being able to take his hounds out for several days at least.

It was very cold, but no snow had fallen when Lord Marlow, pardonably pleased with himself, arrived at Austerby, bringing Sylvester with him. He whispered in his wife’s ear: “You see that I have brought him!” but it would have been more accurate to have said that he had been brought by Sylvester, since he had accomplished the short journey in Sylvester’s curricle, his own and Sylvester’s chaise following with their valets, and all their baggage. The rear of this cavalcade was brought up, some time later, by his lordship’s hunters, in charge of his head groom, and several underlings. Sylvester, it appeared, had sent his own horses back to Chance from Blandford Park. Keighley, the middle-aged groom who had taught him to ride his first pony, was perched up behind him in the curricle; but although the postilions in charge of his chaise wore his livery the younger Misses Marlow, watching the arrivals from an upper window, were sadly disappointed in the size of his entourage. It was rather less impressive than Papa’s, except that Papa had not taken his curricle to Blandford Park, which, after all, he might well have done. However, his chaise was drawn by a team of splendid match-bays; the pair of beautiful grey steppers harnessed to the curricle were undoubtedly what Papa would call complete to a shade; and to judge from the way this vehicle swept into view round a bend in the avenue the Duke was no mere whipster. Mary said hopefully that perhaps this would make Phoebe like him better.

Phoebe, in fact, was not privileged to observe Sylvester’s arrival, but since she had frequently seen him driving his high-perch phaeton in Hyde Park, and already knew him to be at home to a peg, her sentiments would scarcely have undergone a change if she had seen how stylishly he took the awkward turn in the avenue. She was with Lady Marlow in one of the saloons, setting reluctant stitches in a piece of embroidery stretched on a tambour-frame. She wore the white gown purchased in Bath; and as this had tiny puff sleeves, and the atmosphere in the saloon, in spite of quite a large fire, was chilly, her thin, bare arms showed an unattractive expanse of gooseflesh. To Lady Marlow’s eye, however, she presented as good an appearance as could have been hoped for. Dress, occupation, and pose befitted the maiden of impeccable birth and upbringing: Lady Marlow was able to congratulate herself on her excellent management: if the projected match fell through it would not, she knew, be through any fault of hers.

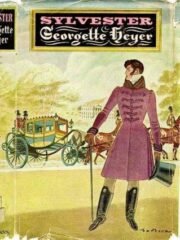

"Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Sylvester, or The Wicked Uncle" друзьям в соцсетях.